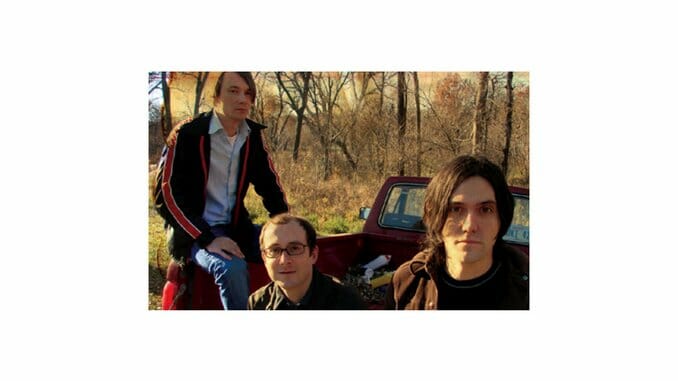

Bright Eyes – Cassadaga

Conor Oberst trains his camera lens on landscapes blurring past

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-