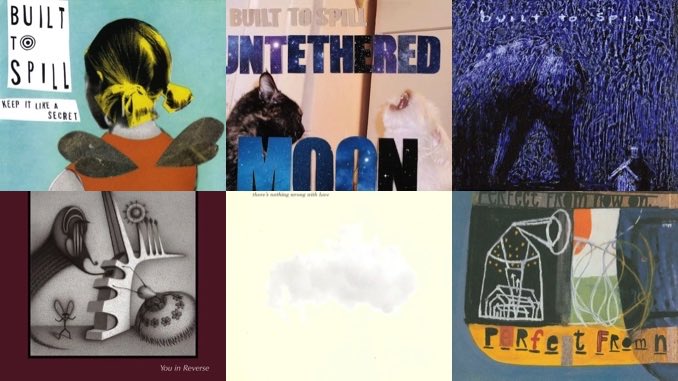

Every Built to Spill Album, Ranked

Doug Martsch isn’t a lyrics guy. For the three decades Built to Spill has existed, he has insisted that his goal with lyrics is just to make sure they’re not bad or embarrassing. When asked in 2015 why he doesn’t talk about the meaning of his songs, Martsch replied, “Well, because a lot already don’t have any meaning, or the meanings they do have are often more subconscious connections than actual meanings. I’m not really a storyteller and I’m not really a lyricist. If I could get out of the lyrics game I would. To me, it’s important that music has singing, and that the singing is actual words, and that the words, they have to be at least okay. They can’t be horrible.”

His melody first, lyrics later approach is a perfect encapsulation of Built to Spill’s understated power. He insists that his aim is simple—to create a good melody and to make sure the words aren’t distracting—but his songs often unfold into expansive interrogations of life, purpose, the universe, and how our past informs our future. He is alternately endearing and heady, but he doesn’t care about being the sage hero of his own songs. He is content to be an unobtrusive background for the endless supply of kick-ass riffs.

The beauty and the mystery of what Doug Martsch does is how these humble goals alchemize into such colossal, gorgeous albums.

While playing in the influential Boise band Treepeople, Martsch formed Built to Spill and departed from Treepeople shortly after. His band began with a specific philosophy: Each album would be recorded with entirely different personnel, other than Martsch himself. He wanted to have freedom of movement to new cities, as well as creative freedom, and not locking himself into a specific lineup would afford him that.

Over nine full-length albums and one singles collection, Martsch has etched an iconic sound into indie rock. If there were a Mount Rushmore for riffs, Built to Spill would need their own separate Mount Rushmore. At this point, he has inspired as many aspiring guitarists as his own guitar heroes like J. Mascis. In a recent interview with Steven Hyden at Uproxx, Martsch expressed, with typical modesty, how perplexed he is at his reputation as a guitar god. “I grew up with bands that had lead guitar players and guitar solos. J. Mascis was really big for me, and Neil Young, too. Just melodic guitar playing. I never really had the greatest tone and skills at all. I’m not fast.”

Modesty aside, that melodic guitar playing is exactly what Built to Spill gave to indie rock—an oft-imitated blend of classic rock and East Coast indie rock, filtered through a laid-back psychedelia. Martsch’s warbly tenor and his purposeful jamming may recall Neil Young in places, but the sound he created is so distinctive that each album feels like a fresh mystery unfolding every time it gets played. No matter how well you remember them, you’re compelled to listen again, to follow the winding threads to their dizzying climaxes.

Built to Spill’s ninth full-length album—their first for fellow PNW stalwarts Sub Pop—When The Wind Forgets Your Name comes out today, Sept. 9, and to celebrate the impossibly consistent career of an unassuming rock hero, we’ve ranked the band’s deep catalog.

10. The Normal Years

The origin story. The charming, ramshackle collection of the band’s earliest material from ’93-’95, originally written to take Treepeople in a new direction, has many flashes of who the band would become. However, the most interesting part of The Normal Years is how clear Martsch’s influences are, and it’s fun to see how they begin to fit together. The cover of Daniel Johnston’s “Some Things Last a Long Time” begins as a faithful cover of the lilting pop song, and ends partially obscured by Sonic Youth-style squalls of noise.

The music being released on Seattle indie label K Records also clearly made an impact. “Girl” and “Joyride” have a childlike, twee-punk quality that feels informed by bands like Beat Happening. Martsch would play frequently with label founder and Beat Happening songwriter Calvin Johnson, notably in their chaotic project The Halo Benders. The two songwriters would each pen their own lyrics to a song and perform them simultaneously, usually as if they could not hear what the other was doing.

The early versions of songs that would appear again on There’s Nothing Wrong With Love are fun curios but lack the magic of their later counterparts. This “Car” is slower and swaggers more. The jam in the middle is sillier, and the walking guitar line makes it feel snarkier than the genuinely affecting version on TNWWL. “Some” is all solo, no lyrics at all.

Even more than those two songs, “Still Flat” might be the clearest signpost of Built to Spill’s future, a slow burn with Martsch’s vocal melody at the center, adding horns as it patiently builds. Like the album as a whole, it doesn’t reach the heights of anything that came later, but it maps the template Martsch would build on for decades.

9. Ancient Melodies of the Future (2001)

I know this will sound ridiculous coming from someone who has it ranked 9th on his list, but Ancient Melodies of the Future is underrated. It never had a chance: Anything that came after the towering success of Keep It Like a Secret was going to feel like a letdown. This particular letdown, however, was severe enough that fans who were around for its release are still bitter. You’ll see it sitting at the absolute bottom of a lot of people’s lists.

And there’s a reason for that. There’s a turn away from the scintillating guitar interplay of its predecessor and toward the wide-eyed simplicity of There’s Nothing Wrong With Love, but the magic is missing. Opener “Strange” and penultimate singalong “Fly Around My Pretty Little Miss” are catchy highlights; the middle drifts and sags.

However, this has been the most unexpectedly rewarding of my relistens for this ranking. There are some monster riffs, and the way Martsch roots around for new melodies makes it a really pleasant listen top to bottom. It may have fewer highs than most Built to Spill albums, but there may also be fewer lows.

8. When The Wind Forgets Your Name (2022)

If Ancient Melodies feels unfocused, When The Wind Forgets Your Name feels exhausted. Interviews from the rollout of both albums finds Martsch discussing, in his usual flat affect, his lack of inspiration. In an interview with Inlander, Martsch said, “[C]reatively, I didn’t feel inspired at all; I felt a little bit shut down and didn’t really have much creative juices flowing. But we had begun the record right before COVID, and my plan all along was to make the record at home on my computer. So, you know, it kind of worked out well, but it was a little bit like pulling teeth. I didn’t have a lot of fun making the record.”

And, yeah, some parts feel like he wasn’t having fun. Slow songs like “Fool’s Gold” and “Elements” suffer the most. The album feels directionless in places. There are contradictory references to the deaf and blind: Sometimes they can see and hear and sometimes they can’t. It’s not even really clear why he keeps invoking them. On “Understood,” Martsch says you can’t figure out life, it’s just understood, but really, he doesn’t know. It’s a few steps in one direction and a few steps back the opposite direction.

However, the songs with any urgency at all shine. “Gonna Lose” and “Never Alright” rock in a way that feels like condensed You in Reverse, and “Spiderweb” is a gorgeous groover that fully delivers on all the album’s ideas. The past two or three Built to Spill albums have one truly standout track that feels fated to be a live favorite—“Going Against Your Mind,” “Pat,” “Living Zoo.” You can toss “Spiderweb” on that pile. It’s a good record, and if history is any indication, it will continue to grow on me in coming years.

7. Ultimate Alternative Wavers (1993)

This is where Built to Spill really gets going: their first full-length. It is much closer to the tin-can production and raucous energy of The Normal Years than anything that came after—“Lie for a Lie” most closely recalls the early slacker rock—but the songs are more fully formed. It’s the first record to feature Brett Nelson on bass, who would become a permanent fixture in the band down the line. Ralf Youtz, who would not return as frequently, played drums.

From “The First Song,” the template of keening vocal melodies and muscular guitar leads is clearly established. “Three Years Ago Today” has some of the sincere charm that would really bloom on There’s Nothing Wrong With Love. “Shameful Dread” and “Built Too Long” sprawl out past eight minutes, foreshadowing the ambitious songs marked by multiple movements that would characterize later work (although “Built Too Long” is as scrappy and off-the-wall as anything on The Normal Years).

Built to Spill’s influence on PNW indie rock can’t be overstated. Martsch and Isaac Brock of Modest Mouse frequently reference the other’s music as an inspiration. Ben Gibbard started Death Cab for Cutie as a Built to Spill-knockoff band, and their first two albums are heavily indebted to the first two Built to Spill albums.

The foundation for the house that Doug built is here: skronky solos informed by equal parts classic rock, Dinosaur Jr. and Sonic Youth; guitar parts stacked to the ceiling; a driving energy that keeps any of the jam sections from feeling sleepy. Ultimate Alternative Wavers sounds like a band right on the cusp of harnessing something powerful and magical. As it turns out, that’s exactly what it was.

6. You in Reverse (2006)

Following the breezy aimlessness of Ancient Melodies of the Future, You in Reverse starts off feeling like a manifesto. There’s a strong case to be made for “Goin’ Against Your Mind” as the best Built To Spill song. The chorus chugs urgently; the guitars stab one moment and, the next, unfurl like butterfly wings from a chrysalis.

After a decade of Phil Ek production, getting glossier with each release, You in Reverse is a rough-and-tumble left turn. Steve Lobdell, owner of Portland’s Audible Alchemy Studios, is credited with “co-production,” but in press releases, Martsch stressed that Lobdell acted more like an auxiliary member of the band. “It’s not even really produced,” he said. “It’s cleanly recorded and mixed. It’s not slick.” You in Reverse is a ranging and roving album that finds its inspiration by burrowing deeper into itself. Reviews at the time complained about the album’s long songs, but the wooly jamming was the central focus when creating the record.

You in Reverse was the only truly collaborative writing process in the band’s catalog, banged out in a series of jams in Martsch’s garage in an attempt to shake loose the cobwebs that Martsch felt settling in after Ancient Melodies. Jim Roth and Brett Nelson joined Martsch in writing and recording the album’s guitars, and in the most impassioned sections, you can almost hear the guitarists handing off the baton as riffs segue. Even when the album slows down and pulls it back, it does so to great effect, like on the beautiful career highlight “Liar.” Twinkling guitars interlock over a bouncy groove laid down by longtime Built to Spill contributors Nelson and Scott Plouf.

The loud stuff is the highlight here, though. “Conventional Wisdom” dances around gleefully, its main riff screaming in at twice the volume of anything else in the song, and it’s one of the most joyful moments in Built to Spill’s catalog: Martsch tearing off a lick that he liked so much he had to keep turning it up. There’s funny little danceable breaks and solos that give way to more solos that, in turn, birth another solo.

Some sections drag, but most of the album’s problems stem from sequencing issues. After the unstoppable freight train of “Goin’ Against Your Mind,” there is a bizarre stretch of the album’s slowest tunes. “Traces” gets lost between the opening track and “Liar,” and the go-nowhere haziness of “Saturday” slows the album to a crawl. It’s not hard to see why so many people quit on the album, which is a shame, because the run from “Mess With Time” through “The Wait” is one of the best in the band’s catalog.

5. Untethered Moon (2015)

Why is Untethered Moon so underrated? My guess is people just didn’t listen to it. Coming as a surprise with little fanfare six years after There Is No Enemy, it has the blessing of feeling unburdened by the pressure of being Built to Spill, and the curse of not having obvious singles. I think casual fans have been waiting for something that grabs them like “The Plan” to reinvest in the band, and while that isn’t coming, I think it’s a shame that many people have passed on such a good album.

It’s simple: The songs are good. “All Our Songs” careens out the gate, as if to recapture the energy of “Goin’ Against Your Mind,” and it isn’t far off. “Living Zoo” is one of the best songs the band has ever written, a sunbaked canter with spider-legged lead lines that goes through a few tempos before settling into a warm, Neil Young-inflected jangle. Demure pop tunes like “Never Be The Same” have a cheekiness to them that recall the band’s early work. “Another Day” is a woozy rocker that feels familiar but not faded, constantly making deft little turns into a new riff or texture.

Thanks to Sam Coomes of Quasi at the boards (and on various keys), Untethered Moon has some of the best production in the band’s history, which lends reinvigorated energy to the spacious jam sections. The lyrics are as inscrutable and stoned as ever, but somehow more emotionally direct than the band had been in years. “Where where did you go / Why did you leave / What did you know,” Martsch laments on “So.” “Living Zoo” ponders how to walk through the hell of existence while “being a human / being an animal, too.” “There’s nothing in the past but that’s alright,” he says on “On the Way,” dismissing the pull of nostalgia and turning his face to the future.

4. There Is No Enemy (2009)

There Is No Enemy came only three years after You in Reverse, but was hailed as a return to form—a reawakening. It was the first Built to Spill rollout I remember being conscious of as a teenager, and I remember thinking the band must have broken up and reunited because of how people were treating this album like a comeback album.

Now, a decade and a half into being a fan, I can hear what all the old heads heard then. The guitars in “Aisle 13” shimmer and slither, doing a full circuit of the band’s classic tropes in less than three and a half minutes. It feels like a song Martsch has tried to write on a few albums and finally succeeded. This impression deepens on “Hindsight,” which takes the warm slide guitar and restrained pop focus from Ancient Melodies and perfects it. “Hindsight” would fit right in on Ancient Melodies and would also be the best song on it. “Good Ol’ Boredom” is a steady, driving slow burn, a joyful six-minute riff showcase that feels half that length.

Songs like “Oh Yeah” and “Things Fall Apart” employ the towering majesty of Perfect From Now On, but the best stuff here is catchier and breezier. See: “Done,” with its twinkling leads and UFO sound effects, and the earnest drive of “Planting Seeds.” The album deals more in good-natured grooves than the scorching solos-on-solos of the band’s more rockin’ efforts, but it reveals a melodic core to Martsch’s music that operates just as well—or better—when unencumbered by the aspiration to make a perfect record.

“Pat” is an anomaly for the band, a return to the punk energy of Treepeople, which is itself a moving tribute to Martsch’s late former bandmate and founding member of Treepeople, Pat Brown. It’s the angriest and saddest Martsch has ever sounded on record, and I’d be doing any discussion of this album an injustice if I didn’t just end with the lyrics to this song:

Pat, we need your brains back / Pat, we need your fire and your imagination / Pat, we know you fucked up / But we don’t care you fucked up, everybody’s fucked up … Thought you’d gone too far for us to take you back / But distances like that, Pat, don’t exist in fact.

3. Keep It Like a Secret (1999)

If this was the only album Built to Spill had released in the ’90s, it would be the best guitar-focused indie-rock album of the decade. It’s the stunning conclusion to a three-album, five-year run. The process of writing and recording Perfect From Now On left Martsch depleted and burnt out, so he intentionally set out to make an album of shorter songs. Nothing but the closer “Broken Chairs” approaches the epic length of the songs on Perfect, which is part of what makes this album an accessible starting point and an enduring favorite even for casual fans. Written during a series of jams with Nelson and Pouf, Martsch reportedly triggered a tape recorder with his foot whenever he felt they were on to something, and pieced the songs together later over painstaking months.

Keep It Like a Secret was the third album produced by Ek, who helped the band progressively expand their sound with overdubs and studio polish. The songs on this album absolutely sparkle. “The Plan” plants a flag in the ground from its opening seconds. Soaring verses driven by big guitar strums and a walking bassline give way to instrumental sections flecked with chiming guitars that bleed into one another—stuttering and thundering one moment, gently fading in and out the next. “Center of the Universe” is even shorter and hookier, anchored again by the now well-established rhythm section. Vocal overdubs from Martsch float throughout the songs, adding another melody on top of the interlocking guitars.

“Carry the Zero” is the album’s centerpiece and the enduring evidence of Martsch’s place in the indie-rock hall of fame. There are no less than three perfect guitar tones, to say nothing of the riffs themselves, which are so achingly perfect they feel like they’re engaging in a call and response with Martsch’s vocals. And we’re only three songs into the album.

“Time Trap” packs an album’s worth of riffs into five minutes. “You Were Right” repurposes the cliches of rock bands and turns them into a rambling rocker that feels, somehow, like a mission statement for the band. If you’ll allow me the indulgence of a few timestamps: “Temporarily Blind” has too many punch-the-air triumphant moments to count. There’s the ethereal pinprick at 1:28; the lockstep drum and guitar part at 1:53, which is among the most ripped-off chunks of music in the indie-rock canon; the stacked guitar solos that begin at 3:50 and last only 10 perfect seconds before disappearing. The fact that this song is followed by “Broken Chairs” is unbelievable to me even as I type it now.

2. There’s Nothing Wrong With Love (1994)

There’s Nothing Wrong With Love starts by clearing its throat: There’s a little noodling and faint clatter before the song proper starts, and the off-the-cuff vibe is intentional. “It was a little bit of a reaction to what was happening in music, where grunge was really taking off with Nirvana and all that stuff,” Martsch told Uproxx. “It’s a lot of clean guitars and it’s not grungy at all. It doesn’t sound tough. There’s no attitude to it. It’s just kind of sweet and straightforward.”

Straightforward undersells it, however. “In the Morning” makes it a minute and a half into its strummy singalong before abruptly slowing way down and expanding into a massive riff. The timeless fan favorite “Car” is a sweet and melancholic medication that smacks into snotty verses before sliding into an unexpected interlude of dramatic strings.

There’s a wide-eyed spirituality, images from childhood swirled into adulthood, recorded as a kind of reaction to the cresting grunge wave. “Twin Falls” strolls through Martsch’s childhood, the rare biographical song, exceedingly tender and affecting. The K Records influence is still there, but filtered through Martsch’s stoned stargazing. “Isn’t it strange that I can dream / Isn’t it strange that I have brain activity,” Martsch muses on “Cleo.” A lot of the lyrics fall into Martsch’s tendency to be coy and cryptic, treating the lyrics as secondary to the melodies. However, some of the most memorable line deliveries come from this album. On “Distopian Dream Girl,” Martsch says, “My stepfather looks / Just like David Bowie but he hates David Bowie / I think Bowie’s cool / I think Lodger rules, my stepdad’s a fool.” It rocks.

There’s Nothing Wrong With Love is open-hearted and unhurried. It’s the sound of Martsch closing his eyes and riffing until he found something that felt vital, with no map at all for where he was headed. It’s the sound of someone unknowingly creating a map that countless others would follow. “That was the last record when I was able to make music without thinking a lot of people would hear it,” Martsch said in a 1999 interview with SPIN. “It makes a difference. I’d like to think it doesn’t matter, but it does.” It’s the kind of album that can only be made when you think no one is watching.

The album is playful, winding, goofy, and gorgeous in equal measure. There’s a giddy freedom to it. “I was really super in love at that time,” Martsch said to Uproxx. And you know what? You can hear it.

1. Perfect From Now On (1997)

In the heady days of the indie-rock gold rush, the success of There’s Nothing Wrong With Love prompted Warner Brothers to offer Built to Spill an unexpected major-label deal. The band would remain there for over two decades. The label deal gave Built to Spill access to fancy studios and a much bigger budget. With the newfound freedom to create, Martsch set out to create his vision of a perfect album. He had witnessed the swift commercialization of grunge and resisted the idea that his music should be shoved in people’s faces like an advertisement. In order to ensure listeners discovered his music on their own terms, he intentionally wrote songs too long for radio play. Only “Made-Up Dreams” falls below the five-minute mark.

What resulted was one of the most labored and disaster-plagued recording projects of all time. Martsch initially tried to record everything except drums himself, but was dissatisfied with the result, and Nelson and Plouf were brought in to help re-record all the songs at Avast! Recording Company in Seattle. Ek liked the resulting recordings, and packed them in his pickup truck to record overdubs back in Boise. On the drive, the tapes melted and became unusable.

The entire album was recorded a third time, again with Nelson and Plouf. The process was so draining that Martsch refused to tour behind the album for over a year. He just couldn’t play the songs any more. However, the adversity had the unplanned advantage of making the band incredibly tight. Everyone involved agreed: The songs sounded best the third time.

I’m belaboring the labor that went into the album because it’s such an essential part of what makes the whole thing work. If There Is Nothing Wrong With Love was an album that could only have been made unselfconsciously, Perfect From Now On was an album that could only have been made with meticulous, all-consuming intensity.

The album—again, their first for a major—opens with a six-minute, philosophical slow burn titled “Randy Describes Eternity,” where the narrator describes eternity. This is one of the craziest sequencing decisions in history. However, it’s a perfectly fitting start for an album that wants you to look up, past what’s familiar and into the mystery. The album continually gazes outward at the cosmos, reflecting on the smallness and enormity of everything as guitars crescendo all around.

“Stop the Show” is three or four different movements packaged together as one mammoth rock song. Eight-minute opus “Velvet Waltz” builds so patiently you don’t even realize the urgency is gaining until the song is already at a full boil. “Out of Site” slows it down as a fake-out, just before shifting into high gear to kick a ton of ass in the last minute. “Kicked It In The Sun” does all of this but somehow even better. Picking a favorite Built to Spill song feels pointless; the magic is how many massive guitar-rock monoliths Martsch erected while remaining human at the center of it, tender and curious. But today, if you want my pick, it’s “Kicked It In The Sun.”

Perfect From Now On is an enormous record with more good ideas in each song than most bands have in entire albums. Every transition into a new riff feels inspired, and every winding solo finds its way back to a triumphant conclusion. The unassuming, flannel-clad Martsch, fresh off his first big record deal, shuffled into the studio with the intention to create one of the great American rock records.

And he succeeded.

Keegan Bradford is a freelance writer, editor at The Alternative, and guitar player in the band Camp Trash. He lives in Portland, Oregon, with his wife, dog and cats. His work has appeared in Stereogum, Vinyl Me Please and Bandcamp Daily, and he can be found on Twitter @FranziaMom.

Watch a 2012 Built to Spill show from the Paste archives below.