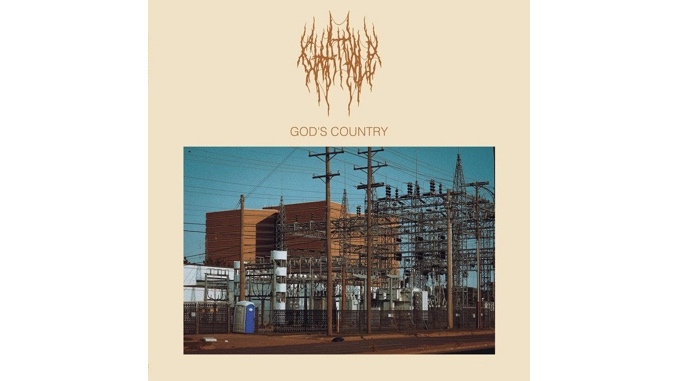

On God’s Country, Chat Pile Peels Back the Rotting Flesh of a Nation

Chat Pile’s debut LP ends with a nine-minute narrative that sounds outlandish on paper: A man is tormented by a nightmare figure resembling McDonald’s mascot Grimace, to the point of suicide. The surreally macabre premise is heightened all the more by the track’s name: “grimace_smoking_weed.jpeg,” a title calling to mind a tossed-off joke file name or online message to a friend in lieu of an actual image. But the song itself is arguably the most chilling selection on an already-bleak record, in no small part due to vocalist Raygun Busch’s tortured contributions that sound an inch from self-destructive action at a moment’s notice—even before erupting into agonized shrieks in protest of the “purple man” who haunts him. When the track’s back half stretches into a sludgy death march, his lyrics become all the more direct, culminating in Busch crying out, “I don’t wanna be alive anymore / Do you?” The pressure of the track proves to be so suffocating that even Busch’s final scream of Grimace’s name to close the album becomes bloodcurdling, where a more ironic approach would have rendered the whole thing high camp.

“Grimace_smoking_weed.jpeg” is, in microcosm, emblematic of the tricky balance Chat Pile evokes with visceral ugliness throughout God’s Country. The absurdity and paradox of capitalist landscapes are laid bare, depicted with just as much horror as the band believes they ought to merit. Just as characters for fast-food marketing and toys become taunting reminders of the soul-crushing nature of post-industrialization, so, too, does the illogical nature of houselessness in a nation with buildings to spare, and the pursuit of wealth above personal fulfillment.

The oppressive nature of God’s Country makes all the more sense when considering the group’s socioeconomic perspective as a Midwestern death metal band, paying firsthand witness to the scenes they paint and mutate into grotesque, noisy vignettes. Luther Manhole’s densely jagged guitar tones firmly reflect the sound of the most sweltering atmospheres of landlocked states, even before this geography explicitly appears in Chat Pile’s lyricism—where their local Oklahoma locales are rendered from the record’s very beginning as places marked by “hammers and grease.”

Though the first-person stories that dot God’s Country are primarily rooted in the grief and financial strain pressuring its characters into their drastic actions, brief flickers of specific Midwestern scenery permeate the album. A man’s daydreams about oceanic vacation getaways are torn to shreds as he’s stuck in the dehumanizing pursuit of money in Middle America on “Tropical Beaches Inc.” “[Staring] at the lake” breeds both the passive resignation of “waiting to die” following the death of a son and the urge to “spill [others’] blood” as retribution for unjust deaths on “Pamela.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-