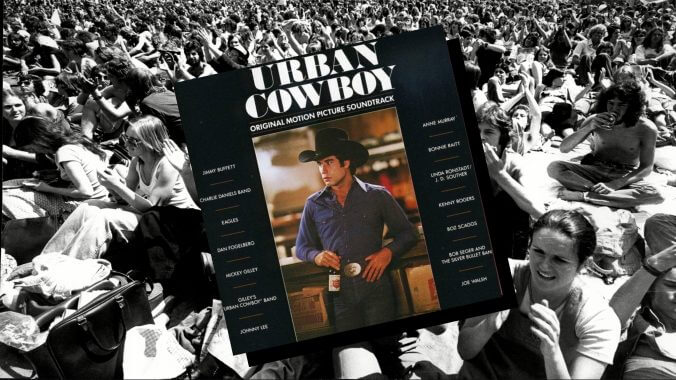

Time Capsule: Various Artists, Urban Cowboy: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack

Every Saturday, Paste will be revisiting albums that came out before the magazine was founded in July 2002 and assessing its current cultural relevance. This week, we’re looking at the movie soundtrack often credited with sparking the widely-panned explosion of pop-country in the 1980s—an album full of time-worn country cuts that feel more like a collage than a compilation of songs shouldering the burden of one genre’s commercial downfall.

When she was younger, my mom had a John Travolta pillow as a kid (him as Vinnie Barbarino in Welcome Back, Kotter, specifically), and my dad will watch Saturday Night Fever anytime it’s on syndication. Even I found a bit of charm in Travolta’s turn in something like Wild Hogs, years before I went through my cinephile era and found Blow Out. There’s a soft spot in my household for Travolta and the complex highs and lows of a long, 40-year career he’s so narrowly kept afloat at various intervals. But all roads lead back to Urban Cowboy, a no-questions-asked masterpiece in the eyes of my kin. I don’t particularly agree with that pedestal placement, though I am guilty of voluntarily re-watching it every year or so. What endures for me is the film’s soundtrack and its place in conversations around the long, complicated downfall of commercial country music.

Urban Cowboy wasn’t the same definitive landmark film that Saturday Night Fever was, but its box-office successes spawned from Travolta’s (seemingly) bulletproof fame at the time. It made $53 million on a $10 million budget, and Vincent Canby of The New York Times even said it was “not only most entertaining, but also first-rate social criticism.” In 2024, the film’s portrayal of blue-collar workplaces is pretty lackluster beyond the showing of the thing (the various scenes of the oil refinery workers actually on-site), but filmmakers have found much more empathetic, kind and authentic ways to engage with conversations around class in their projects. But, between you and me, James Bridges’ romance western is deeply, deeply flawed on numerous levels and, likewise, revered for reasons that exist beyond the film itself. In actuality, Urban Cowboy’s successes rest greatly on the shoulders of the mainstream country music revival it spawned in the immediate aftermath of its release. And to many, that resurrection is seen as a net-negative for the genre as a whole—a take I can’t quite throw my weight behind.

Coined “neo-country disco music” by God only knows who, the pop-country saturation of the 1980s is often linked to Urban Cowboy’s soundtrack. Critics and customers alike saw the soft-rock boom of the mid-1970s collide head-on with disco’s death rattle and swallow outlaw country whole and neglected to praise it. This movement, however, was but a blip in country music’s legacy—as country sales hit $250 million in 1981 but, by 1984, clocked in lower than the figures from 1979. It was, by all financial accounts, a trend that burnt out as quickly as it was lit in the first place. However, by 1984, nearly a thousand radio stations across the United States were playing country and neo-country pop music full-time. Catch yourself anywhere between the coasts in 2024 and you’ll likely find a radio dial with more country stations than not.

It’s practically taboo to consider something like that happening now, though. The film industry doesn’t have the firepower anymore to completely transform an entire genre of music, but it’s also evident that the music industry—especially the mainstream music industry—is too spread out and diverse in 2024 to experience such a shift, even the oft-segregated milieu of country music. That’s why you get think pieces on how Garth Brooks and his soundalikes ruined country music in the 1990s, or social media threads about how the post-9/11 divide in the genre that led to feuds between folks like the Chicks and Toby Keith had ramifications that are still being felt now, just mere months after Keith’s passing. Everyone wants to know what spurred the downfall of country music, but pointing to a film like Urban Cowboy—which never found the courage to truly say anything worthwhile about the working class or, even, era-specific bar culture—is low-hanging fruit.

At this point, the “tractors, trucks, beer and women” critique of country music is a tried-and-tired lambasting that has grown way too thin and, in actuality, buries the lede on what’s actually hindering country music in contemporary spaces: a cocktail of fervent sexism, racism and general anti-LGBTQIA+ sentiments. Country music suffers from being one of the only genres left that feels so terminally sectioned off, and you can see parallels of that in Urban Cowboy, too—as Travolta’s Bud is a maniacally abusive, violent dude who hits women. While there’s quite an intoxicating amount of homoerotic energy buzzing through the movie, the way Urban Cowboy so habitually blurs the lines of bar culture with abuse and archaic depictions of gender norms is just the tip of its problematic, poorly-aged iceberg. Like Barry Corbin’s Uncle Bob says at one point in the film, “pride’s one of them seven deadlies,” and Urban Cowboy’s got a whole mess of pride.

Regularly, the women in Urban Cowboy are treated like set-dressings for the film’s male characters—but only when it’s convenient to them. Take Wes Hightower (Scott Glenn) for instance, who regularly flaunts his sexual partners in front of Sissy (Debra Winger) and then hits her relentlessly when she doesn’t bend to his wants. The only time a woman performs a song on-stage during the film—when Bonnie Raitt sings “Don’t It Make Ya Wanna Dance” beautifully—a bunch of cowboys start tussling with each other and make a sweaty boy pile all over the bar floor. One part of the film is even dedicated to a bunch of women dressing up like Dolly Parton for a sexualized “lookalike contest” that makes no sense as a plot point. Like I said, Urban Cowboy is deeply flawed. Only in a film so chaotic and profoundly malicious could a scene with a bunch of men fan-girling over a punching bag arcade game foreshadow an entire runtime of non-stop hedonism (hey, the 1980s!). The saving grace of the movie is its music—the Hill Boogie flourishes that made Houston, Texas a Hollywood darling for a moment frozen in time (Andy Warhol, of all people, came to town for the film’s premiere).

While the Saturday Night Fever soundtrack changed the landscape of pop and dance music entirely in 1977 and remains a near-picture-perfect performance of disco and soul music, Urban Cowboy found commercial luxuries, too. You might say that whatever popularity came its way was an unavoidable reward for existing at an expansive, 20-year apex—where soundtrack LPs were making an ungodly amount of money (see Top Gun, Dirty Dancing, Super Fly and Purple Rain, just to name a few)—but there are a lot of gems in the Urban Cowboy stable, and Raitt, Johnny Lee, Charlie Daniels and Mickey Gilley even show up to play their tunes at the bar, lending an authentic dimension to a bonafide dress-up movie.

The film’s soundtrack is responsible for five Top 10 hits on Billboard’s Country Singles chart, and it featured two #1 hits from the decade prior. Just six years ago, the record was certified 3x Platinum by the RIAA on account of the three-ish million copies sold in the 44 years since its initial release—thanks to an initial double-LP-only printing and a CD re-release in 1995. Featuring folks like Jimmy Buffett, Dan Fogelberg, the Eagles, Anne Murray, Linda Ronstadt, Gilley, Raitt and the Charlie Daniels Band, the Urban Cowboy soundtrack is a very sweet mesh of folk and country rock. Given just how lukewarm the response was to the country revival it’s credited with generating, it’s rather shocking (in a good way) just how easy on the ears all 18 songs end up hitting—it’s a greatest hits compilation parading as a film companion, but I’ll take these tracks any way they come.

The internet will tell you that the plot of Urban Cowboy is Bud and Sissy’s tumultuous love-hate relationship with each other. Well, I’m here to tell you that the plot of Urban Cowboy is macho-wachoism centered around a mechanical bull in a football field-sized bar that’s “3-and-a-half acres of concrete and prairie.” The honky tonk, Gilley’s, was founded by Sherwood Cryer in 1971 and operated in partnership with country singer Mickey Gilley—who enjoyed quite a career revival from the movie, as his cover of “Stand By Me” hit #1 on the country chart in the summer of 1980. And let’s be honest, if you’re familiar with Urban Cowboy at all, it’s likely because of that mechanical bull (and the general Travolta-ism, of course) and nothing else.

The film, though, is a time-capsule that, despite the onslaught of chart successes that came from its soundtrack, still feels entrenched in an era that predates what was meant to come next for country music. Tracks like the Eagles’ “Lyin’ Eyes” and Bob Seger & The Silver Bullet Band’s “Nine Tonight” only mesh with the Urban Cowboy-ism of it all faintly. Even Boz Scaggs’ “Look What You’ve Done to Me” and Joe Walsh’s “All Night Long” are rock tracks that don’t immediately conjure honky tonk bar imagery. They’re radio dusters and soft-spoken ballads that exist in the background because they hold no place closer to the surface. When Bud and Sissy have their first wedding dance to Anne Murray’s “Could I Have This Dance,” it’s a needle-drop that could’ve existed anywhere—not necessarily a song choice that would really land with the “shit-kickers” decamped at Gilley’s every Saturday night, but one that echoes the falsified togetherness that Bud and Sissy share together.

Instead, it’s Jimmy Buffett’s “Hello Texas,” the Charlie Daniels Band’s “The Devil Went Down to Georgia” and Linda Ronstadt and J.D. Souther’s “Hearts Against the Wind” that make Urban Cowboy’s western costume look and sound all the more real. Hell, throw Kenny Rogers’ “Love the World Away” in there, too. (It’s surprising that there are no Elvin Bishop needle-drops in the film, if I’m being honest.) What’s most unfortunate, however, is that the best country songs in the entire film don’t appear on the soundtrack at all: Johnny Lee and Mickey Gilley’s cover of Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson’s “Mamas Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up to Be Cowboys” and the Charlie Daniels Band’s “Texas.” Considering those omissions, I’m left wondering what the overall shape of the soundtrack becomes if you nix Scaggs and Walsh’s tracks in favor of the aforementioned two.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-