Boy Howdy!: Scott Crawford’s CREEM Doc Digs Up Rock ‘n’ Roll’s Only History

If CREEM was, as every cover touted, “America’s Only Rock ‘n’ Roll Magazine,” then Boy Howdy! The Story of CREEM Magazine, which recently debuted at the SXSW Film Festival, is our nation’s only rock-mag documentary. Director Scott Crawford captures the beloved publication’s notorious irreverence with some help from famous fans, but it’s the stories from those who worked at CREEM during its heyday—like senior editor Jaan Uhelszki, who co-wrote the film with Crawford—that get to the heart of a magazine that helped launch the careers of a generation of rock writers.

The doc brings to life CREEM’s biggest personalities who often clashed over their passions for music, journalism and, of course, the money that kept the whole operation afloat. Publisher Barry Kramer fired the founding editor Tony Reay shortly after launching CREEM in 1969 and brought on writers like Dave Marsh, Lester Bangs, Sylvie Simmons, Cameron Crowe, Robert Christgau, Greil Marcus, Chuck Eddy, Lisa Robinson and Uhelszki, who once wrote about getting on stage with KISS in full make-up.

Uhelszki got her start for the magazine as a teenager in Detroit, when she was working at the Grande Ballroom as a “Coca-Cola girl.” Next to her was a kiosk that sold copies of CREEM. “I said, ‘If I give you a free Coke, can I write for you?” she recalls. “That’s how it started—a lot of free Cokes.”

She moved her way up the masthead and looks back on the experience as a special moment in the history of rock journalism.

“It was the early days of Big Rock,” she says. “There was no one covering them—rock criticism was in its infancy. So the stars would come to us because they wanted to be covered. People showed up at the office all the time. So we never thought that they were gods. We always talked to them like they were common people. So that barrier didn’t exist. You could make fun of them, they’d make fun back, and it would be a different kind of interview. So that spirit of fun and irreverence people talk about, it’s really a product of the times.”

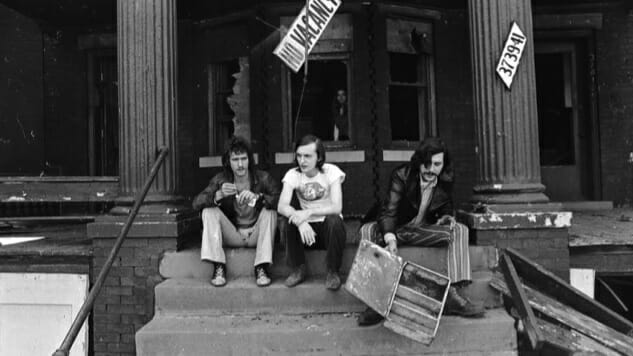

Kramer, who died in 1981, could be a difficult boss, moving the operation from Detroit to a 120-acre commune in rural Walled Lake, Mich., where the staff both lived and worked for a few years. For Kramer’s son, J.J., a producer on the film who was just four-years-old when his father died of a nitrous oxide overdose, the filmmaking process was something of a chance to learn more about his dad.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-