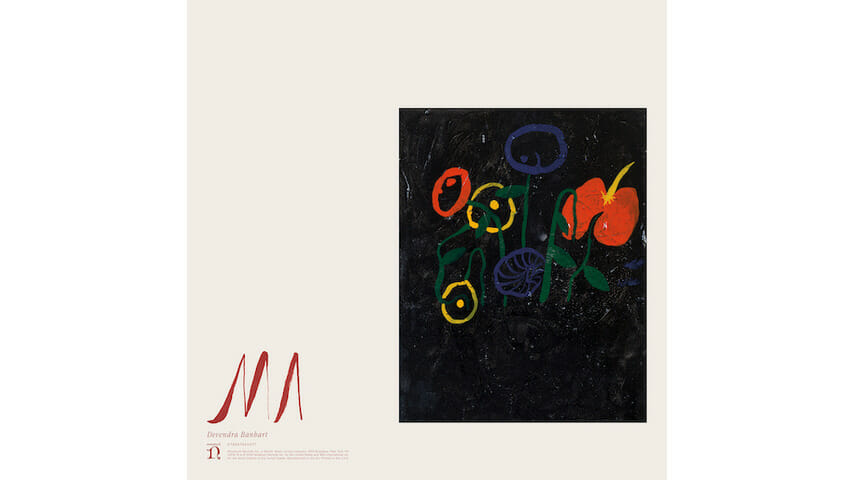

Devendra Banhart Embraces Motherly Love on Ma

New album features the singer’s most cohesive songs yet

When Devendra Banhart released his fragmentary 2002 album Oh Me Oh My, the bits and pieces of songs felt like an intimate glimpse into an itinerant life. Recorded in friends’ apartments and other makeshift spaces in cities around the world, the album was a jumble of lo-fi production values, wandering tempos and fantastical, possibly stream-of-consciousness lyrics. It was also the lynchpin of “freak-folk” in the 2000s (a term soon considered insulting by many of the people it was applied to), and the bearded, beatific Banhart became something like a spiritual guide for the scene.

His music over the intervening years has often been considered experimental, even as it has become less overtly rooted in psychedelic folk. Though it’s certainly an intimate record, Ma, his latest, retains few other markers of his eclectic origins, emphasizing instead the most cohesive songs and sophisticated arrangements that Banhart has delivered to date. It’s a chamber-pop record, full of string arrangements and woodwinds alongside acoustic guitars, bass and drums.

As the title suggests, Ma is ostensibly about maternal love, and not always in a literal sense. Though he sings lovingly about his own mother, and the bonds between mothers and children in general, there are also several songs about Venezuela, a sort of motherland where Banhart spent much of his childhood.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-