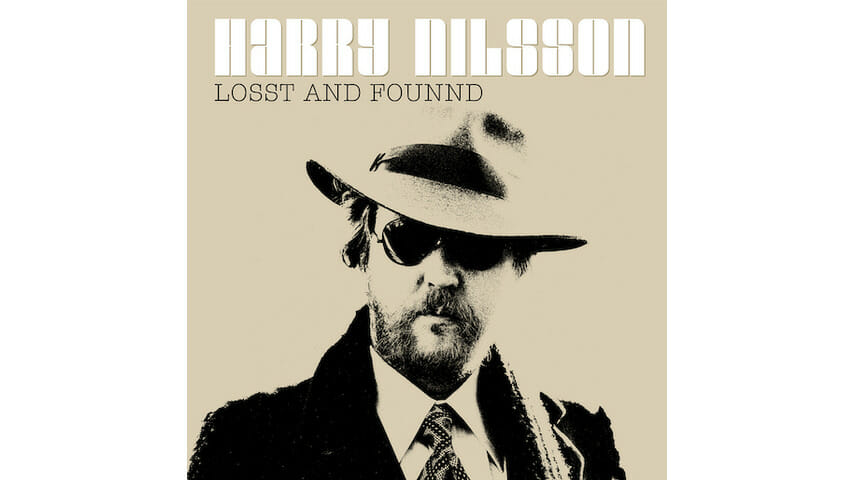

Harry Nilsson Serenades Fans From Beyond the Grave on Losst And Founnd

25 years after his death, Nilsson’s uneven but affectionate last album is finally released

Like his old pal and drinking buddy John Lennon, Harry Nilsson died right as he was plotting a comeback. After spending most of the ’80s in retirement (prompted in part by the trauma of Lennon’s murder), Nilsson had decided in the early ’90s to return to active musical duty. By then, the devilishly imaginative singer behind hits like “Everybody’s Talkin’” and “Coconut” had fallen on difficult times, including serious health problems and the unwelcome discovery that his financial manager had embezzled his lifelong earnings. He needed cash.

After surviving a massive heart attack in early 1993, “he started writing and recording in earnest, hoping for a hit that would secure his family’s financial future,” Dawn Eden recounted in what would be Nilsson’s final interview. Of course, there would be no hit. The singer died on January 15, 1994, just days after completing vocal tracks for his would-be comeback record. It was thusly shelved, seemingly for good.

In 2019, that comeback finally seems to have arrived—only Nilsson isn’t here to enjoy it. Early this year, the jovial Nilsson Schmilsson classic “Gotta Get Up” served as the theme song for Netflix’s Russian Doll, introducing the singer’s work to a millennial audience. Several months later, millennial spokeperson Carly Rae Jepsen lovingly borrowed a Nilsson hook for the best track on Dedicated. Now, after 25 years of bootlegs and rumors, Nilsson’s last album, Losst and Founnd, is finally seeing release. It’s been newly completed by its original producer, Mark Hudson, who recruited a handful of the singer’s old buddies—Jimmy Webb, Van Dyke Parks, even Nilsson’s son Kiefo—to contribute. (Evidently, the original tapes were rough: “It just was Harry and I in the room with him chain-smoking and me playing every instrument,” Hudson told the Washington Post recently.)

Like Nilsson Schmilsson, Losst and Founnd flits restlessly from style to style, emphasizing the singer’s eclecticism and sense of humor. And while the songs are hardly as great as that 1971 masterpiece, nor the production as timeless, it is nice to hear Nilsson’s voice anew. His playful wit shines on “U.C.L.A.,” a lightly funky post-apocalyptic lament to a world he no longer recognized (including the dramatic irony of the late Nilsson singing lines like “There’s no more Ringo Starr”). It’s the kind of song that captures the surrealness of this project: long-abandoned 1990s recordings of a 1970s songwriter completed in 2019. Other appealing stylistic turns include “Woman Oh Woman,” a lush achievement in piano-and-accordion popcraft, and “Listen, The Snow Is Falling,” which transforms the 1969 Yoko Ono song into a slinky, slide-guitar groove.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-