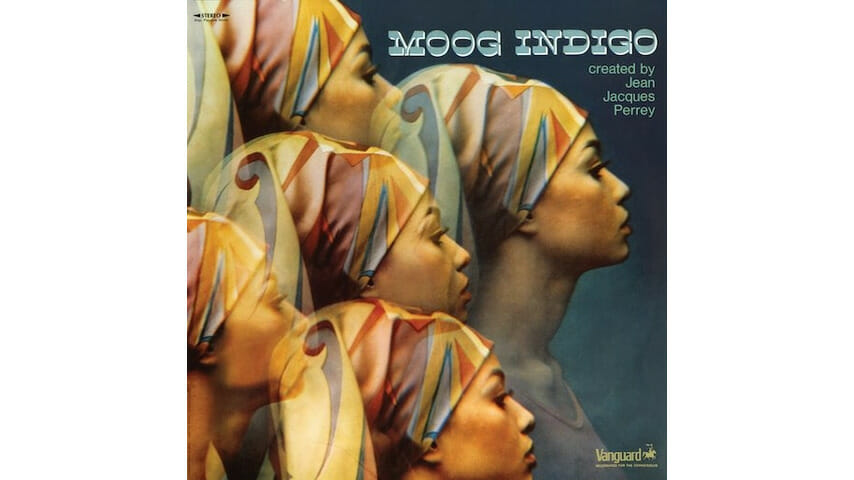

Jean-Jacques Perrey: Moog Indigo Reissue

In the heat of the space race, as U.S. corporations and advertisers tried to whet the public’s appetites for all things astronomical, they were coincidentally aided by the innovations struck by Don Buchla and Robert Moog. Both men were working to shrink the size of modular synthesizers down from the hulking machines that filled an entire room to something more manageable and playable by studio musicians and concert performers. And the bleeping, wowing, almost rude sounds that could be created by these instruments were the perfect stand-in for all things technologically advanced, alien and groovy.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-