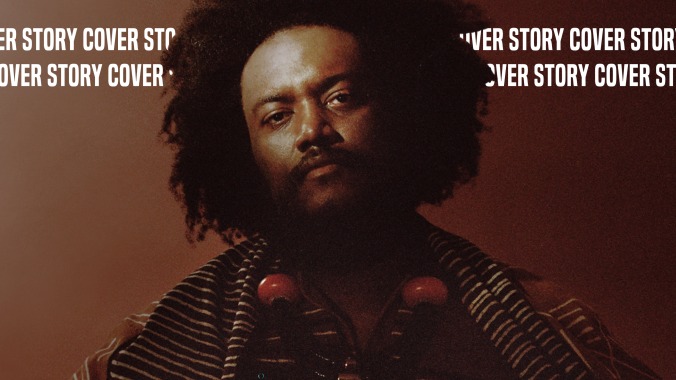

For Kamasi Washington, This is Just the Prologue

For our latest Digital Cover Story, the Los Angeles-based tenor saxophonist and bandleader discusses dancing, George Clinton, fatherhood and his no-wrong-notes mentality.

Photo by Vincent Haycock

Kamasi Washington has never made a dance record before. With Fearless Movement, that’s about to change, at least in terms of its conceptual framework. The Los Angeles-based tenor saxophonist, composer and bandleader, on albums like 2018’s Heaven & Earth and 2015’s The Epic, delved into cosmological motifs of grandiose proportions. Although Washington’s music hasn’t lost any of its celestial nature, Fearless Movement explores the simple act of dancing as a form of expression. Dancing is intrinsic to music itself, whether Washington makes a straight-up house record or continues pursuing spiritual jazz, like he does on his latest album.

Washington comes from a musical family; his aunt, Lula Washington, is a renowned and influential dancer. She would frequently babysit Kamasi and his brothers, who would end up spending days at her studio. It wasn’t until Kamasi got a bit older, though, that the magnitude of Lula’s dance career truly struck him. Lula worked with McCoy Tyner, the jazz pianist and composer who played in the John Coltrane Quartet, a musician whom Kamasi counts as one of his heroes. He had always respected Lula’s art, but it was at that particular moment that Kamasi realized the unbreakable connection between jazz and dance, something he was only subconsciously aware of as a child.

“When I was younger, I had this connection between highly improvisational and expressive music and dance, and, for whatever reason, generally, those things are split apart like they’re two different things,” Washington explains from his LA home via Zoom. “I’ve always wanted to explore that more: the idea of making music that I’m intentionally wanting people to move and to express [themselves] with.” So he set out with that goal in mind when working on Fearless Movement. He wanted to create something that he could imagine Lula and her dancers using in a performance; he wanted to create something in which the listener was a direct, active participant in the making of its meaning. “I felt like it would just be fun to make music that people wanted to join in on rather than just listen,” he continues. “That seemed fun to me, to have people release and let go. There is a sort of release and letting go when you allow yourself to dance. Even for people who aren’t dancers, there’s a similar thing.”

As adults, we’re often reluctant to truly let go and dance, out of a fear of other people judging us or thinking we look outright foolish. Children, though, usually have no inhibitions. That’s a realization that Washington witnessed himself when he recently became a father; to say the least, it’s a fairly significant life change that he has undergone in the time since his last proper album. In fact, you could say that his daughter, who is now just shy of two years old, has already become one of his collaborators; Akili Asha Washington wrote the melody on the aptly titled “Asha the First.” He recalls one day when she was sitting at the piano and toying around with various chords and phrases, at first, seemingly at random. Then she had an epiphany: If she played the same keys, then they would elicit the same sounds, but if she played up or down from that starting note, then it would sound different. Stunned by this discovery, she looked at her father, mouth agape, with utter joy. She was certain she was showing her father something that had never been documented in the history of the human race.

“Everything [children] do is new; every experience is a new experience,” Washington says. “And as we get older, we learn these comforts. We learn what’s safe. But that childlike musical energy is powerful. that freedom that children exude. I’m learning from her in that way. She’s not afraid to say anything. She’ll try anything, so she’ll play anything on piano. Nothing is wrong for her. There are just different versions of right.” To Washington, the significance of dance flourishes in that childlike sense of freedom, the will to cast aside any self-imposed hindrances and chase that moment of escape from the drudgery of modern existence. When he talks about his daughter, his enthusiasm is palpable. His face beams with delight any moment she comes up in our conversation. She taught him an invaluable lesson: There are no wrong notes. “There are no places that you can’t go,” Washington continues. “To me, that is the final frontier.”

Washington intended to start recording another album much sooner, but, understandably, becoming a parent will stall that process by a year or two. Even then, Fearless Movement wouldn’t be the record that it currently is had he not become a father beforehand. Such a consequential life chapter inevitably shapes everything you do, including your art. It’s a sentiment he bears in mind. “It’s a monumental experience to truly discover unconditional love, and it changes who you are,” he muses. “We have people that we care about and that we would put our lives in danger for, but it’s different, like this person is more important than me. That’s actually a beautiful state to be in to release you because, now, life isn’t about you. It changes the perspective that you see things. Music is such a reflection of who you are and how you see things, that change definitely affects how I make music.”

Now, Washington no longer identifies as a musician first and foremost. He considers himself a father first and an artist second. Musicianship is still integral to his self-perception, but it’s not the primary occupant anymore. “You go from having your identity being like, ‘I’m a musician,’ and then that takes a backseat,” he says. “Now I’m a father, and that transition was one that I wanted to do, but it took some courage on my part to let go, to be able to be comfortable with it and not be fearful that, ‘Oh, I’m losing something. I’m not going to be what I am.’ But I’m not going to let anxiety or worry take over. That’s part of what the album is about to me: living in your true, current self and not being afraid to change because, sometimes, it’s easier to hold on to what you are than to be what you want to be.” This is the impetus driving Fearless Movement, the notion of letting matters take their natural course and seeing what becomes of them.

Washington took that direction with the compositional side of the record. Although he still set out with the aim to make people dance, he didn’t want that concept to restrict where the music would go or what it would mean to other people. He refused to put an album centered on freedom into a proverbial box. “How I’m hearing music right now is in that space of fearlessness, which is letting it be what it wants to be,” he says. As far as maintaining his mission for making listeners want to dance, however, he focused on building these songs from a rhythmic foundation. He and his bandmates, including Tony Austin on drums, Miles Mosley on double bass and Brandon Coleman on keys, to name a few of them, would frequently start by deciding how the rhythm section would go. They’d then see how the rest of the tune would develop from there.

One of the most rhythmically driven tracks is “Asha the First,” which not only features Akili’s melody, but also Thundercat (AKA Stephen Bruner) on electric bass and twin rappers Taj and Ras Austin of Coast Contra—all of whom augment the track’s heavy syncopation. Washington and Thundercat have a long history together, from releasing 2004’s Young Jazz Giants with the latter’s brother, Ronald Bruner Jr., and Cameron Graves, to serving as key members of Kendrick Lamar’s backing band on 2015’s To Pimp a Butterfly. With Ras and Taj, he “randomly found them on the internet” and became quickly enamored of “their flow and their whole style.” He had a chance encounter with them at the Hollywood Bowl, where they were performing.

“We had the song, and I wanted some youthful energy to it,” Washington recalls. “I thought it would be cool to have them rap over something that wasn’t a loop, and it’s like the music is just going. They’re rapping and flowing with the musicians in a way that I thought was really dope. It’s like the words and the music are really contrapuntal and interacting with each other.” And that’s exactly the effect that “Asha the First” pulls off. As Ras and Taj zigzag around frantic drums and a labyrinthine structure, they eventually find themselves back in the pocket, right alongside the hypnotic groove, locked in. It sounds like a group of musicians in a room responding to each other in real time, conversing and trading ideas. Like all 12 tracks on Fearless Movement, it sounds like a dance as much as it makes you want to dance yourself.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-