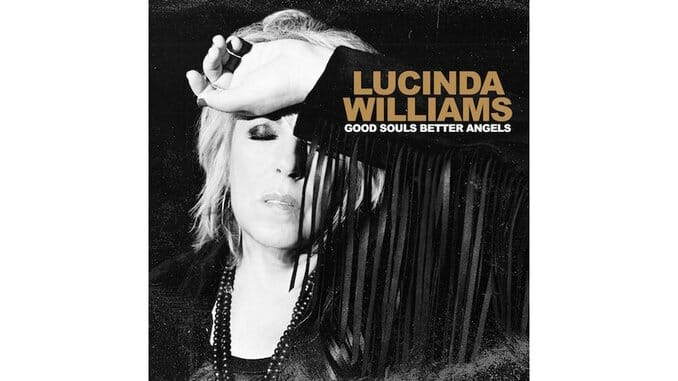

Lucinda Williams Returns With Enlightened Fury on Good Souls Better Angels

The alt-country luminary puts her songwriting chops to use on an album that—maybe for the first time in career—truly verges on protest music

Have you ever been afraid of Lucinda Williams? The renowned singer/songwriter can be scary when she wants to be. Just listen to “Changed the Locks,” from her 1988 self-titled album, which was full of love songs like “Passionate Kisses” and “I Just Wanted to See You So Bad” as well as regret-tinged backlashes like “Price to Pay” and “I Asked For Water (He Gave Me Gasoline).” “I changed the lock on my front door, I changed the number on my phone,” she sings. “I changed the kind of car I drive, I changed the kind of clothes I wear.” All those adjustments—just to get revenge on a man, just to make sure he never touches, or even gets near her, ever again. Few know their way around a country revenge song like Williams does.

She’s back in that blazing saddle right out of the gate on her new album Good Souls Better Angels, a sweltering garage-country record that wastes no time when it comes to the airing of grievances. “You can’t rule me,” she declares in her immediately recognizable groan on track one, instantly reminding her listeners why we fell for her smoky spell nearly 40 years ago. Whether she’s berating an abusive man in her own life or just a man abusing the powers placed upon him, this song is scathing. “Well the game is fixed, it’s plain to see,” she sings, practically growling. “I ain’t playin’ no more.”

Williams’ refusal to play along with the evils of today’s political landscape is what drives Good Souls Better Angels, her 14th studio album in four decades of monumental music-making. You won’t have to look hard or wide to find someone moaning about the relentless news cycle that’s been inescapable since 2016, but no one is singing about the omnipresent bad vibes like Williams. “Who’s gonna believe liars and lunatics / fools and thieves and clowns and hypocrites?” she asks (the answer: a lot of people, as we’ve learned) on “Bad News Blues.” “Gluttony and greed and that ain’t the worst of it / all the news you could read, all the news that’s fit to print,” she continues, poking fun at the New York Times’ centuries-old motto, which, now, in light of so much unflattering news, seems almost like a funny museum relic. The “bad news” is everywhere: in our “sinks,” “drinks,” “mail” and “trails.”

-

-

-

-

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 3:10pm

-

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:57pm

- Urls By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:57pm

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:55pm

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-