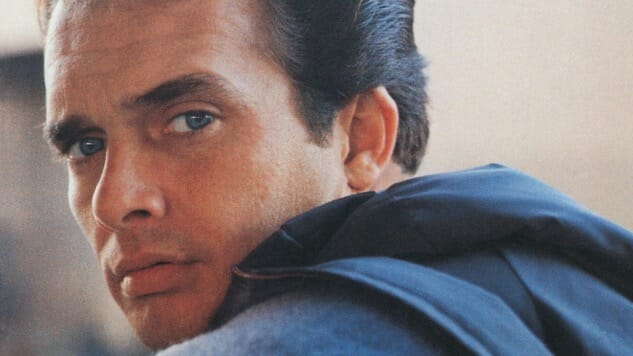

Remembering Merle Haggard, Country Music’s Renegade Realist

When I interviewed Merle Haggard in 2002, I asked him to explain the difference between Southeastern country music and West Coast country music. He answered by asking a question of his own. Did I know why Southern Baptists don’t screw standing up? I didn’t. “Because,” he chortled, “someone might think they were dancing.”

It was a classic Haggard moment: unpredictable, irreverent and hinting at a deeper truth. He didn’t care about the country music taboo against mocking religion; if he had a chance to share a good story—even one as short as a joke—he would tell it and tell it well. And dancing was a key difference between country music in the Deep South, where it got started, and in California, where Haggard and like-minded renegades revamped the genre in the ‘50s and ‘60s.

Haggard, who died Wednesday at age 79, was a 21-year-old inmate in California’s San Quentin Prison in 1958 when Johnny Cash performed there (11 years before the famous album). That show made the young con believe that he too could become a singer and songwriter. So when Haggard was paroled, he headed straight for the bars of Bakersfield, California, where young guys like himself were plugging in bright, chirpy Telecasters and driving the beat hard enough to make tired oilfield workers, farmhands and cannery workers fill the dance floors.

Soon Haggard was writing lyrics as tough and as aggressive as the underlying music. It’s often said that country music is a combination of Saturday night and Sunday morning. Well, the new music coming out of Bakersfield definitely leaned in the Saturday-night direction. And Haggard’s lyrics transformed that high-octane dance music not with homilies from Sunday morning but with true stories of the first of the month, when all the bills came due without money enough to pay them.

In Haggard’s hands, the barreling-train rhythm of the Bakersfield Sound was not just an emotional release from the work week. It was also a blast of anger at a fate that offered only the unappealing options of poor-paying work, prison or the hobo life. Preachers and parents could try to get him to accept that fate like a good boy (“Mama Tried,” he sang), but he was having none of it. He was going to let Saturday night and the first of the month bang up against each other till the sparks flew.

“The songwriting came from an off-center situation: the barroom,” he explained. “It wasn’t easy for us, because we had all the mothers against us. Prior to 1950 and Bakersfield’s appearance on the scene, most country music was inspired by church music. Hank Williams sounded like a Southern preacher with a good voice. They wouldn’t even let him sing the word ‘beer’ on the Grand Ole Opry. They wouldn’t let anyone use drums on the Opry. They made Bob Wills put the drums behind a curtain.

“When I was a kid, I thought everything was like Bakersfield. I thought everyone had a good time like we did. Then I started touring and went down South and found they didn’t have Saturday night dances. That’s why they don’t like me.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-