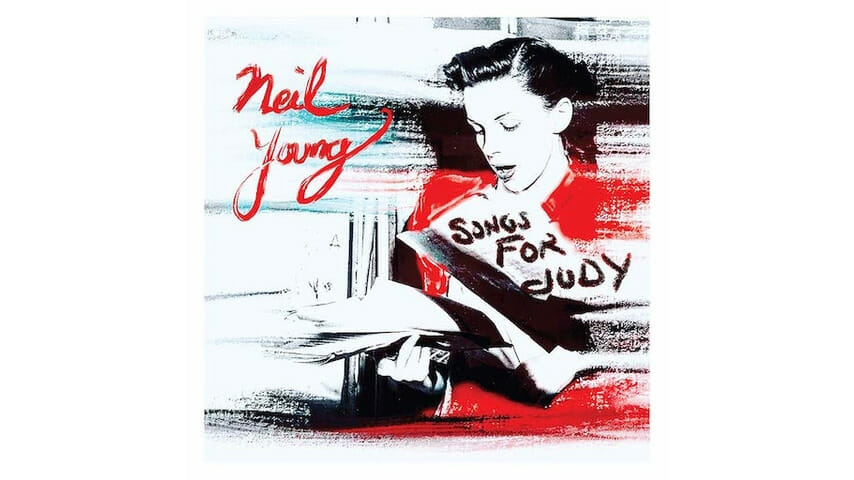

Neil Young: Songs For Judy

Neil Young’s latest archival album, Songs For Judy, is his twenty-fourth live recording but stands out for its focused scope and for the historical moment that it conjures. The record comprises twenty-three live cuts from the U.S. leg of Young’s 1976 tour with Crazy Horse, which ended a few days before the singer joined The Band for their final show, immortalized on film as Martin Scorsese’s The Last Waltz. With that context in mind, Songs For Judy arrives as an uncanny anachronism, a sonic snapshot of an artist mid-flight of a major career ascent. Since Young has released five studio albums in the last five years (and shows no signs of slowing down), hearing Songs in 2019 feels akin to discovering a loose floorboard in an attic with an intriguing time capsule buried under the wood.

The performances captured on Songs For Judy derived from Young’s practice of surprising crowds with an acoustic set before plugging in with Crazy Horse, and the tracks radiate camaraderie, intimacy and the mind-freeing affordances of cannabis. Among the collection’s most charming moments would be a loopy monologue that precedes “Too Far Gone” and gives the album its inside-joke of a name. Above the screams and whistles of the crowd at Atlanta’s Fox Theater, Young launches into a back-and-forth with the “loud, boisterous mothers out there,” first teasing and then telling an anecdote about how he spotted Judy Garland earlier that night “down in the pit there,” in a red dress and red lipstick, holding the sheet music for “Somewhere Over the Rainbow.” Given that Garland died seven years earlier from a barbiturates overdose, the notion of her ghost calling up to Young asking, “How’s the business, Neil?” sets a tone: bordering on the profane but always brushing up against the mystical.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-