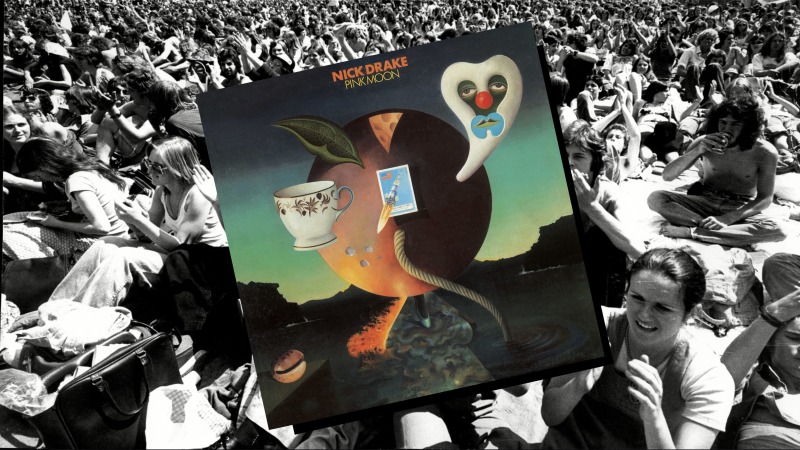

Time Capsule: Nick Drake, Pink Moon

In Nick Drake’s short discography, Pink Moon lingers as his parting breath. It's a faint and final masterpiece—a deserted isle of shy lyricism and haunting acoustic work that sheds all pretense of fame, form, and, heartbreakingly, even life itself.

Why is it that the most brilliant voices in music get snuffed out right as they reach their peak? Just imagine a post-Band of Gypsys Jimi Hendrix diving deeper into psychedelia and exploring funk throughout the 1970s, or picture the landscape of modern music had Kurt Cobain stuck around and the band continued to evolve after In Utero. But instead, we mythologize these artists at the height of their careers, encasing them in prophetic amber before time can dull their glow. There’s an unshakeable (and arguably toxic) romance between an early death and artistic immortality—a superstition sanctified by the morbid exclusivity of the 27 Club. Maybe that superstition began “the day the music died,” when a plane crash in 1959 killed Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and the Big Bopper. Maybe it goes back even further, to Robert Johnson selling his soul at the crossroads. Or maybe it’s a coping mechanism—a cultural sleight of hand to distract us from the uglier truth: that artists depart from us slowly, oft-forgotten by an industry that thrives on what’s marketable, not meaningful.

And then there’s Nick Drake. Drake wasn’t the voice of a generation; in fact, he barely garnered an audience at all. Of the three albums he released in his lifetime: Five Leaves Left (1969), Bryter Layter (1971), and Pink Moon (1972), all were met with a shrug of apathy. Critics gave polite nods but never craved more. Listeners rifled right by his LP sleeves, so sales were dismal at best. As a result, Drake rarely performed live (he was rarely seen in public at all, really), and in 1974, at the age of 26, he died after overdosing on antidepressants. No legend, no blaze—just unceremonious silence. And, for decades, that’s how it stayed. Drake was forgotten by music, by culture, and by legacy, written into the footnotes of music history. A few musicians loved him in the ‘90s, especially Elliott Smith, Chris Cornell, Thom Yorke. However, in 1999, something unexpected happened: A Volkswagen commercial aired, and the Pink Moon title track played behind scenes of a quiet night drive. Suddenly, something clicked: album sales soared, reissues followed, and the world was finally ready for Drake’s artistry, a quarter of a century after his passing.

In Nick Drake’s short discography, Pink Moon was his parting breath. It’s a faint and final masterpiece—a deserted isle of shy lyricism and haunting acoustic work that sheds all pretense of fame, form, and, heartbreakingly, life itself. Recorded in just two nights, the album captures Drake alone with his acoustic guitar, performing each track in a single take. The only exception is “Pink Moon” itself, which features a delicate piano overdub halfway through the intro. Moments where Five Leaves Left and Bryter Layter were ornamented with string passages and lively jazz horns are left bare on Pink Moon, instead looping in fingerpicks and ghostly silences.

When the finished tapes arrived at Island Records, they came without liner notes, photos, or promotional material of any kind—as if Drake had already accepted the album’s fate to be quietly shelved, just like its creator. The footprint of Nick Drake, to me, feels Edgar Allen Poe-ish, not through any shared poetic brooding (though, there is plenty), but through their mutual tragedy. Both artists were geniuses of their time but largely ignored in life, only to be revered after death. Whether they saw themselves as failures or simply couldn’t reconcile their brilliance with the world’s indifference, the result was the same: early exits, posthumous praise, and a looming sense of what could have been.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-