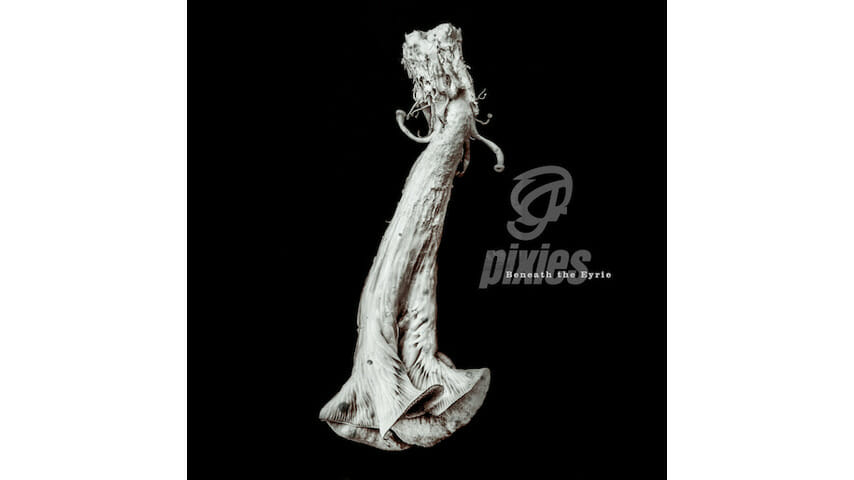

Pixies Are Loud, Weird and Full of Hooks on Beneath the Eyrie

Bassist Paz Lenchantin steps fully into her role on latest album

The Pixies’ latter-day music has made people angry, as if the band sought to personally offend some listeners by daring to sidestep the albums the original foursome released between 1988-91. That’s deeply silly, of course, not least because the band’s new material is better than they’ve been given credit for. Sure, the transitional 2014 album Indie Cindy had some patchy moments, and the rapid turnover in bass players, from Kim Deal to Kim Shattuck to Paz Lenchantin, wasn’t the greatest look. Even amid personal turmoil for some of the members since then—rehab for guitarist Joey Santiago in 2016, a recent divorce for singer Black Francis—things seem to have settled down in the band, and The Pixies’ latest is loud, weird and full of hooks. Is it the second coming of Surfer Rosa? No, but it was never going to be.

The band has a different kind of intensity now than it did 30 years ago. They were subversive pioneers back then, marrying sneaky pop melodies to surreal lyrics and abrasive guitars, and their “loud-quiet-loud” musical dynamic became a kind of shorthand for the alt-rock explosion that spilled into the ’90s. They’re still doing those things on Beneath the Eyrie, but the impact is necessarily different—early songs like “Where Is My Mind” or “Wave of Mutilation” are only groundbreaking the first time around, especially when so many subsequent bands have used The Pixies as a frame of reference. The important question, then, for a present-day Pixies album isn’t whether it calls to mind the old stuff, but whether the songs are any good in their own right as Pixies songs. Admittedly, that’s a high bar, but Beneath the Eyrie meets it.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-