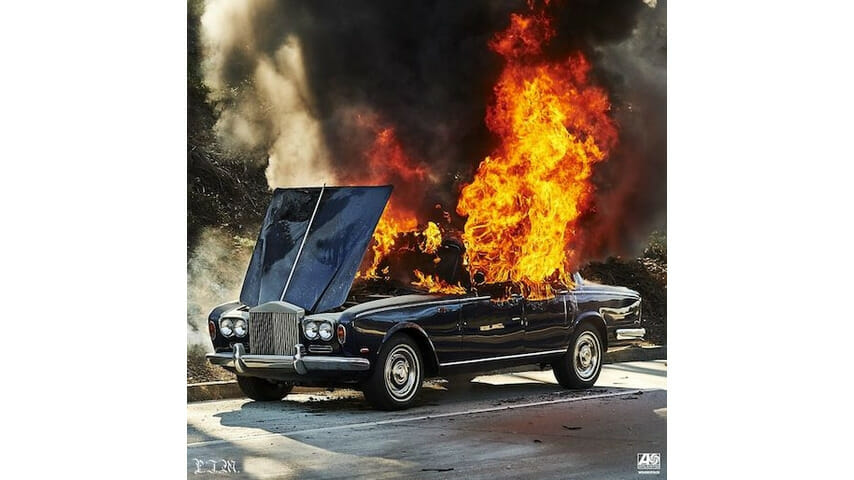

Portugal. The Man: Woodstock

There should be a reasonable explanation for the sharp musical turn found on Portugal. The Man’s eighth studio album, Woodstock. After the release of the Danger Mouse-produced Evil Friends in 2013, the Portland-based outfit retreated again to the studio with the Beastie Boys’ Mike D for three years to worry over the purported follow up Gloomin + Doomin. This record, though, was ultimately scratched very near its completion, and a fateful reassessment of the band’s musical message lead to the revolutionary-minded street-pop of Woodstock after vocalist/guitarist John Gourley came upon his dad’s ticket stub from the original 1969 Woodstock Festival.

This commentary alone doesn’t account for the new record’s headfirst dive into the deep end of contemporary pop. Despite the risk, the record manages to fall in line with Portugal. The Man’s willingness to move forward in endearing ways.

The lede for the album is less than subtle, as Woodstock opens with a dancefloor reimagining of Richie Havens’ famous improvisational finale to his Woodstock opening set, here sung by Son Little. The song is the first indication of Portugal. The Man’s all-in plunge into the dregs of dub-pop. The band’s newfound reliance on studio trickery, sampling, and folding in the tenets of hip-hop production most assuredly stems from their Danger Mouse/Mike D collaborations. But the most interesting part of this transition is that it has been slow, and well-crafted, despite its relative about-face from the choir-like ‘70s punk-boogie of their early days. “Number One” retains the band’s firm grasp on sultry grooves, stemming from the velvety rhythmic lockdown of drummer Jason Sechrist and bassist Zach Carothers.

“Easy Tiger” is driven by a bold drum beat and the subtleties of Kyle O’Quin’s keyboard flourishes. The track’s complex chord shifts usher in schizophrenic pop dalliances, as Gourley’s tenor skitters above the fray like an androgynous nymph. It’s clear that this shifting of the band’s preferred soundscapes is more aesthetically agreeable to Gourley’s vocals, a fact borne out as the record progresses.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-