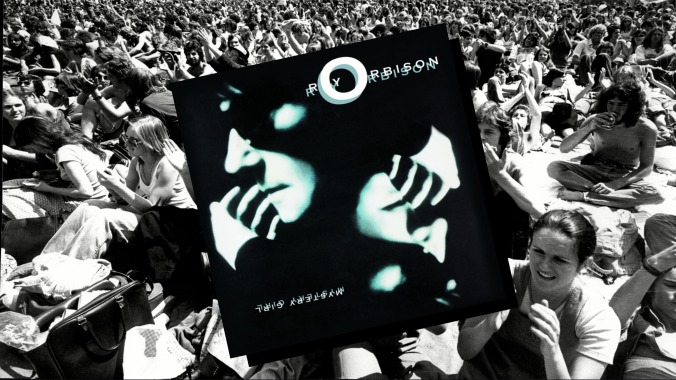

Time Capsule: Roy Orbison, Mystery Girl

Every Saturday, Paste will be revisiting albums that came out before the magazine was founded in July 2002 and assessing its current cultural relevance. This week, we’re looking at Roy Orbison’s curtain call, a critical and commercial success that found the “Only the Lonely” singer surrounded by friends.

In 1987, Bruce Springsteen giddily inducted Roy Orbison into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. “Most of all, I wanted to sing like Roy Orbison,” Springsteen told the audience, recalling the recording sessions for Born to Run. “Now, everybody knows that nobody sings like Roy Orbison.” The Boss was certainly right that Orbison’s voice—three or four octaves in range and stretching from baritone to tenor—had been instantly recognizable since the singer’s chart-conquering string of hits back in the early ‘60s. However, it’s also true that Orbison—habitually clad in dark suits and tinted glasses with hair dyed jet black—had been largely relegated to the shadows by the same industry now honoring him. By the time Springsteen gave his induction speech, Orbison hadn’t released an album of new material in nearly a decade or notched a Top 40 single since the mid-‘60s. However, all of that was about to change in the months to come.

Shortly after Orbison got enshrined, the once-forgotten artist would see his star rise to heights only surpassed by his “Only the Lonely” and “Oh, Pretty Woman” heyday. That ascension would culminate in the release of 1989’s Mystery Girl, Orbison’s first studio album of all new material since 1979, and its globe-trotting hit single, “You Got It.” Suddenly, the singer once dubbed “The Big O” and “The Caruso of Rock”—known for his operatic voice and brooding ballads soaked in tears, loneliness and dreams—sat atop the music world alongside artists like Bon Jovi and Milli Vanilli. It’s a tale of triumph made all the more remarkable, and heartbreaking, because Orbison had already passed away from a heart attack in December of ‘88, a little less than two months before Mystery Girl would hit the shelves. In that light, the album acts as a final curtain call from Orbison, but it also closes the book on an unlikely, heartfelt comeback that saw the artists he had inspired nudge him back into the spotlight for one last encore.

Of course, nothing truly happens overnight. The revival leading to Mystery Girl had been slowly gaining momentum for over a decade, as the next generation of Orbison’s peers rekindled the public’s affection for his music. Everyone from Linda Ronstadt and Don McLean to Nazareth and Van Halen had scored hits with songs written or popularized by Orbison. Maybe the least likely boost came from filmmaker David Lynch’s bizarro use of Orbison’s “In Dreams” in his 1986 neo-noir thriller, Blue Velvet, where a lip-synched version serenades Dennis Hopper’s psychopathic gangster, Frank Booth, to the point of rage-filled tears. Orbison, a film buff in his own right, learned to appreciate the interpretation after originally having been horrified by the scene.

The Big O would jump on his own bandwagon as well, earning his first Grammy Award in 1981 for a duet with Emmylou Harris on “That Lovin’ You Feelin’ Again.” He would also re-record 19 of his greatest hits in 1987, after fearing that the original recordings might be destroyed due to legal issues facing former label Monument Records. Apart from the success of Mystery Girl, the zenith of Orbison’s revival might have been the now-iconic Cinemax special Roy Orbison and Friends: A Black and White Night. Springsteen played sideman to Orbison’s lead, and no less than Elvis Costello, Tom Waits, k.d. lang, Bonnie Raitt and Elvis Presley’s old backing band, among others, filled out the ranks for a night that showcased the singer’s body of work and undiminished power as a singer. lang recalls a grateful Orbison humbly thanking all involved and promising to return the kindness if possible.

Of all the friends Orbison made during the last couple years of his life, arguably none proved more impactful on his career and legacy than producer and Electric Light Orchestra frontman Jeff Lynne. Like Rick Rubin later did for Johnny Cash via the American Recordings series, Lynne would be the primary facilitator for what turned out to be Orbison’s final recordings. Running in Lynne’s crowd at the time found Orbison suddenly rubbing shoulders with fellow icons George Harrison, Tom Petty and Bob Dylan. The serendipitous overlap of Lynne’s production schedule would lead to Orbison hitching a ride with supergroup the Traveling Wilburys and those same bandmates becoming a critical part of his burgeoning Mystery Girl project.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-