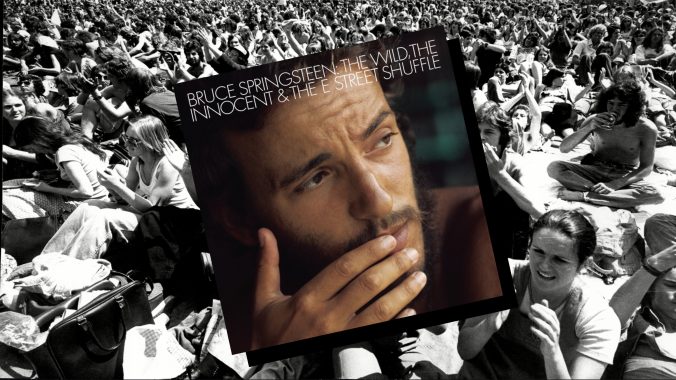

Time Capsule: Bruce Springsteen, The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle

Every Saturday, Paste will be revisiting albums that came out before the magazine was founded in July 2002 and assessing its current cultural relevance. This week, we’re looking at the record Bruce Springsteen made as his opus was knocking on the door of his imagination—an album full of ghosts, summer memories and characters forced to grow up and out of innocent love in the sweaty, damning New Jersey and New York heat.

Bruce Springsteen played, by my estimation, about 210 shows in 1973 (the only time he ever came close to that number again was in 2018, when he played around 175 shows). It was his busiest year by far, as he released two albums—his debut, Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J., and its quick follow-up, The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle—in 11 months, transforming from a bright-eyed Jersey kid in a band called Steel Mill to a leather-clad, blue-collar hero commanding the stage all on his own. If Dylan was the voice of a generation, then Springsteen was the voice of everything else.

Bruce had not yet stepped into Born to Run by this point (though he had apparently come up with the title around then)—he wasn’t yet consumed by the towering haunts of memory and regret and fleeting innocence. No, he was 24 years old and infatuated with the summer vibrancy of the nearby Jersey boardwalk, singing about Rosalita and Sandy and Billy and Jackie and Kitty and Spanish Johnny and Puerto Rican Jane and Power 13 and Little Angel. The streets were filled with pleasure machines and fortune tellers and strongmen and alley rats. For 47 minutes on The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle, there is hope despite a finite amount of life left to live. There are boys dancing with their shirts open; an aurora is rising behind lovers. It sounds like a promise, like someplace you wouldn’t mind falling in love and dying in. You’re not running away from the populous; you’re a cog in its imperfect beauty.

The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle was recorded between May and September 1973 at 914 Sound in Blauvelt, New York. Mike Appel and Jim Cretecos oversaw production, while Springsteen, Clarence Clemons, Danny Federici, Garry Tallent, David Sancious, “Mad Dog” Lopez and Suki Lahav descended upon the studio and banged out seven tracks—none of which clock in shorter than four-and-a-half minutes. There is something about the attitude of The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle that harkens back to jazz, be it the genre’s long-standing gestures of improvisation or its firestorm romance with the Big Band era during the Great Depression.

The E Street Band could rattle off a meticulous, five-steps-ahead composition and a sprawling, 15-minute rendition of a once-four-minute classic all in one breath—dedicating song intervals to letting each member solo and shine. Every section is built through the emphasis of painstaking attentiveness, the energy flowing through them a mark of shared communion and talent that becomes a singular spirit stitched together. Bruce Springsteen’s biographer, Peter Ames Carlin, wrote that The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle marked a “renewed passion for full-band rock ‘n’ roll” for he and the E Street Band, and it’s a declaration that shows. It doesn’t matter how good that run from Born to Run through Tunnel of Love was—it all starts with The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle 50 years ago.

The album begins with a mirage of saxophone, tuba, cornet and clavinet from Clemons, Tallent, Sancious, Lopez and Al Tellone. “The E Street Shuffle” is theme music for the tightest band in America, and Bruce ringing out “Sparks fly on E Street when the boy prophets walk in handsome and hot” is a call to action. You better quit what you’re doing and get some eyes on this, these are phantoms of the alleyways and the backstreets, strutting in their skin-tight leather and ready to make a scene. The weather is hot but everyone’s dancing. This is where we meet Power 13 and Little Angel, who have cheap hustles and parade across Lover’s Lane.

When the band chimes in and howls “Oh, everybody form a line!,” it’s theatrical. Never before had a rock ‘n’ roll album opened with a short story as vibrant as “The E Street Shuffle”; never before had rock ‘n’ roll known the beauty of Detroit muscle and teenage tramps and E Street brats and riot squads. But at the 3:37-mark, Bruce’s guitar solo ruptures into a full-band brass breakdown. He picks up some maracas and begs Clemons, Tallent, Sancious, Lopez and Tellone to drown out the keys and Richard Blackwell’s percussion. It’s not a cheeky name-drop for a backing band. It’s an introduction to a world that, even as it’s dying, has got a date with forever. It’s at the 3:37-mark when The Wild, the Innocent & The E Street Shuffle becomes, as Bruce calls it, “sweet summer nights turn into summer dreams.”

And that’s what The Wild, the Innocent & The E Street Shuffle is—a summer album, maybe the greatest one ever written. Bruce drops us into Independence Day immediately on “4th of July, Asbury Park (Sandy),” a ballad that remains a picture-perfect, arresting arrangement of blink-and-you’ll-miss-it boardwalk memories. It’s not just a love song; it’s a love song about somebody you know you won’t love forever. Sandy is The Wild, the Innocent & The E Street Shuffle’s Wendy, a near-mythical character not placed on a pedestal by our narrator. No, he sees Sandy as someone to long for as the depressions of Jersey grow thicker. Maybe she’s just that night’s beach-bopper dressed like a 10-cent star; maybe she’s one of those locals who’ll never make it across the Hudson.

“I just got tired of hangin’ in them dusty arcades bangin’ them pleasure machines, chasin’ the factory girls underneath the boardwalk, where they all promise to unsnap their jeans,” Bruce admits, straddling the line between putting Sandy on for the sake of a good fuck and being earnestly infatuated with her. Federici’s accordion swallows the foreground melodies while Sancious’ piano and Springsteen’s guitar duet in the background. Bruce’s narrator wants to settle down. The waitress he was going steady with “won’t set herself on fire for me anymore” because she was “parked with lover boy out on the Kokomo.”

I return to “Sandy” often, and not just because it contains one of Bruce’s cleverest lyrics (“Did you hear the cops finally busted Madame Marie for tellin’ fortunes better than they do?”), but because it’s full of now-empty promises that, when they were made, felt as sure as anything in the whole wide world. When Bruce sings “love me tonight and I promise I’ll love you forever,” it’s to the chagrin of a destiny not in his corner. But the laughter underneath the boardwalk, the fireworks over Little Eden, the carnival life and pier lights on the water—you’ve felt all of it, too, be it at a county fair or an amusement park or beneath the metallic bleachers of a high school football game. You remember that feeling like it was yesterday because it was. The genius of “Sandy” is that it’s a time machine.

“Kitty’s Back” is the E Street Band’s big, jazzy brilliance. There’s a reason why it’s the centerpiece of any Bruce Springsteen show in 2024—no song can better showcase just how talented and virtuosic Bruce and his backing band are. It’s one of the few moments in any night’s setlist where the song’s DNA changes in a flash, depending on the ensemble’s energy and mood at that given moment. On The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle, “Kitty’s Back” is an instant change-of-pace from “Sandy,” as screaming guitars converge with the E Street Band’s brass section like a runaway train. Sancious pulls out an organ solo pillowed by Clemons’ tenor saxophone. Springsteen tested the waters with long-winded vamping like this a few years prior on the Steel Mill track “Garden State Parkway Blues,” which would sometimes last 30 minutes before closing and boast slight parallels to what would eventually turn into “Kitty’s Back” in 1973. What I adore most about the song is that it’s practically unfinished—as any great jazz song really is—and could go on for hours beyond the seven-minute runtime we get on The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle.

A song that flourishes through intervals, “Kitty’s Back” crosses the Hudson and finds something to yap about in the 90-degree heat of Bleecker Street. “Well, Jack Knife cries ‘cause baby’s in a bundle,” Bruce sings. “She goes running nightly, lightly through the jungle.” It’s the only part of The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle where Springsteen’s lyricism is weaker than the sound of the ensemble noodling behind him. “So get right, get tight, get down” doesn’t sound like Springsteen, but I’d argue that the messy story serves the track pretty well. It’s loose and feels unrehearsed—exactly how you would describe “Kitty’s Back” at any show, even now. And that’s where the charm endures. “Now, cat knows his kitty’s been untrue and that she left him for a city dude” just sounds cool, even if the street-life picture Bruce is taking registers a bit blurry by the time the E Street Band is done harmonizing a long cycle of scat-like “Whoa, oh, oh, oh, oh, all right, whoa, all right”s.

-

-

-

-

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 3:10pm

-

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:57pm

- Urls By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:57pm

- Curated Home Page Articles By Test Admin October 21, 2025 | 2:55pm

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-