30 Years Later, Timelessness and Forgiveness are the Newest Chapters in Sunny Day Real Estate’s Diary

The venerable Seattle band reflect on their origins and sudden success on arrival, the growth they’ve made amid years of breakups and clashes, and the new poignance their debut record holds on its anniversary.

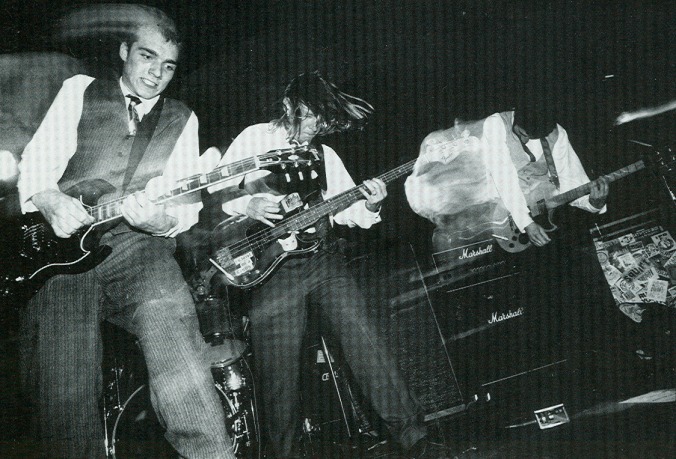

Photos courtesy of Sub Pop

Sunny Day Real Estate can still vividly remember the magic of their earliest days. “I have a really visceral memory,” lead guitarist Dan Hoerner recounts, “of the first time that Jeremy, William and I played together. I had this frisson of electricity that just passed through my body. All the hairs on my arms and the back of my neck were standing up, and I was feeling like I was hearing the best music I had ever heard. I just knew there was something absolutely uncanny and electric happening.” Lead vocalist and rhythm guitarist Jeremy Enigk cherishes what the band captured at its outset with just as much wonderment: “It was like having magical powers, like a weird alchemy. We felt like wizards—or I did, anyway,” he says.

It’s 30 years to the day since the Seattle indie rockers released their landmark debut Diary through Sub Pop at the height of the label’s “Seattle sound” heyday, but the luster hasn’t faded for them in the slightest. They’re still just as enamored with it as their avid, intergenerational listeners, if their eager embrace of the 30th anniversary of Diary via touring and a live album weren’t evidence enough.

And it’s easy to see why: Diary is still a perfect storm of a record. Enigk’s voice elegantly cradles his most tender words in one moment, before charging into wrought screams of pure passion against Hoerner’s harmonies. Hoerner’s riffs grip with an urgency and force that’s matched by William Goldsmith’s precision behind the drums, each snare hit an emphatic punch that sucks the air out of the room, and former bassist Nate Mendel adds a whole melodic dimension of his own, as if creating ‘90s rock’s answer to John Entwhistle. The emphasis on patience and dynamics makes each refrain’s emergence all the more arresting—when a chorus hits on Diary, it explodes. The refrains on “Seven” and “In Circles” and “The Blankets Were the Stairs” wallop like a sandbag dropped on your skull, the sheer force and emotion put into their every syllable rendering them anthemic on arrival.

It’s no wonder a record this potent would see its reputation endure—and, arguably, only grow—with time, even if that reality seemed impossible for the band to fathom back in the early 1990s. Speaking with Hoerner, Enigk, and Goldsmith over Zoom before one of numerous legs in their extensive Diary anniversary tour, one can sense the disbelief still settling in. “I was still in high school,” Enigk says, “and we started to play as a three-piece when Nate was on tour, just for fun. We just wanted to get together. It was really just a thing we were doing in the basement for ourselves.” The three of them never once imagined the reach that these nascent songs they were crafting would have this lifespan, this wide of a reach. Instead, Enigk felt something more important stand out: “There was so much joy and laughter.”

The story and mythology of Sunny Day Real Estate have been well-documented at this point by fans gripped by the band’s idiosyncratic mystique, but hearing these three founding members recounting it and reminiscing is a joy unto itself. In the early ‘90s, Goldsmith was notorious for being in multiple bands at once, to the point where he was playing with Enigk in Reason for Hate while also drumming with Hoerner and Mendel in Empty Set, along with two other bands simultaneously. “There were always issues of bands fighting over who gets to have William,” Enigk says with a laugh. When he heard that Goldsmith was making music with Mendel, he jokingly mentions thinking, “‘We’ve lost William forever.’”Hoerner elaborates: “Nate was a rockstar back then.” Though still relatively young, Mendel already had a wealth of experience under his belt, through stints in Diddly Squat, Brotherhood and Christ on a Crutch. “All of us were just kids, but Nate was already an established god in the pantheon of punk in Seattle.”

Goldsmith describes his initial sessions with Hoerner and Mendel as “really inspired times and huge learning experiences,” comparing the experience to “trying to learn a more sophisticated version of air sculpture.” The worlds of Empty Set and Reason for Hate collided when Hoerner and Mendel heard Enigk performing solo, and brought him on to open for Empty Set at several shows. Soon after, Mendel went on tour with Christ on a Crutch, leaving Enigk, Hoerner and Goldsmith together for the first time. From the project this trio formed from those jams—Thief, Steal Me a Peach—came the earliest bones of what Sunny Day Real Estate would blossom into. “We ditched the 46 songs we wrote previously and then started fresh,” Goldsmith says. “The hardcore scene had a lot of screaming, so the focus on melody and storytelling as opposed to protest was an experiment.” When Mendel returned from tour, the three showed him what they had come up with in his absence, and the change in direction stuck.

From here, Sunny Day Real Estate’s breakthrough happened in a rush that took all involved by surprise. “It was a whirlwind,” Enigk recounts, still stunned. “The next thing we know, we play two shows and we’re already on a label with Sub Pop.” Sunny Day Real Estate played their first two shows at The Crocodile in Seattle, afforded the opportunity by future Sunn O))) guitarist Greg Anderson, whose punk band Engine Kid had to drop from the first of these gigs. Anderson put in a good word for Sunny Day Real Estate to venue booker Erik Soderstrom, and the group took Engine Kid’s place on the bill. “We played that show,” Goldsmith says, “and then Eric said, ‘As an experiment, I’m gonna put you playing first at the Sub Pop showcase that’s coming up.’” Though Goldsmith mentions only “one-and-a-half people” came to watch their subsequent set, one of those was Jonathan Poneman, co-founder of Sub Pop. “He came up and said, ‘Do you guys want to make a record?’ We laughed at first, because it’s a hard thing to process.”

“At the time, Sub Pop was the pinnacle,” Hoerner adds. By then, they had already more than made a name for themselves in the scene by—among other things—putting out Mudhoney’s first releases, reissuing the Wipers’ cult classic Is This Real? and, most significantly, being Nirvana’s first home and the label that released Bleach. “Everybody wanted to sound like Nirvana, and for good reason,” Hoerner continues. “In my opinion, there was no record label that had more cache, that was more important.”

“We didn’t even really look at the contract,” Enigk says. “We just signed it.”

When Diary dropped a mere two years after Sunny Day Real Estate’s formation, its most alluring qualities—and staggering distinction from any of the band’s peers—stood out immediately. One of those was the numbering that governed some of the track titles, such as “Seven,” “47” and “48,” which fans came to ascribe as reference to where each song fell sequentially in the band’s compositional history. (When Enigk joined the band, the mythology went, “48” was the last song to be named as such in the initial sequence; then, Sunny Day Real Estate reset the numbers, and started the count over.)

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-