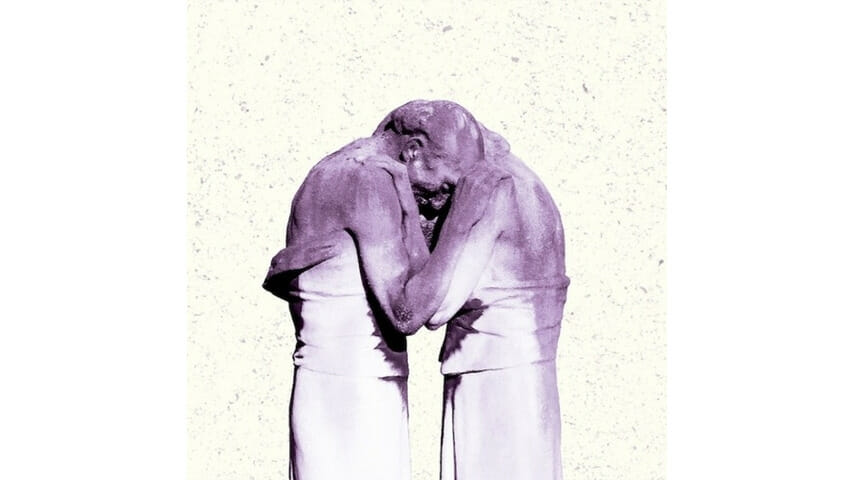

The Antlers: Familiars

“Sad” is a catch-all we use to describe music that turns inward, reflects and exists without concern for how its audience is going to feel about what they hear. It is about expression, relating and both comforting and being comforted. This year has had no shortage of such, from wounded (Lykke Li, Sharon Van Etten, Beck) to pensive (Sun Kil Moon, La Dispute) to the talk of the moment, Lana Del Rey. Speaking with Pitchfork this year, Annie Clark (St. Vincent) described her album closer “Severed Crossed Fingers” by noting, “I sang that in one fucking take, cried my eyes out, and the song was done.” And if you really are versed in pain and need some more advanced product, the freebase of sad, try Lydia Loveless or Strand of Oaks or Angel Olsen. In terms of self-reflective music, 2014 is a banner year.

The Antlers’ fifth LP, Familiars, fits neatly in this conversation, which is no surprise considering their most beloved album takes place in a cancer ward and their last LP ended with a song called “Putting the Dog to Sleep.” But, to simply label these nine songs as “sad” is getting stuck in some of the sonic cues (down-tempo rhythms, beautiful whining trumpets from Darby Cicci); the album is ultimately the most cathartic and uplifting that songwriter Peter Silberman has crafted, indicating the demons he has long wrestled with may be tiring, if not nearing defeat.

Even at his darkest, Silberman has had a knack for crafting beauty out of pain, and that’s where “Palace” begins, with the dual reading of losing sight of your old self or losing connection with a changing love. Either way, the song illuminates the pedestal we place idealized memories on. But musically, it could be a Disney ballad, as unmasked heartstring-pulling as you will find west of “Can You Feel the Love Tonight” and “A Whole New World.” Those songs, jokes aside, are obvious in their intention to make an audience feel a specific vitality at a certain moment, and Familiars finds hope in vitality.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-