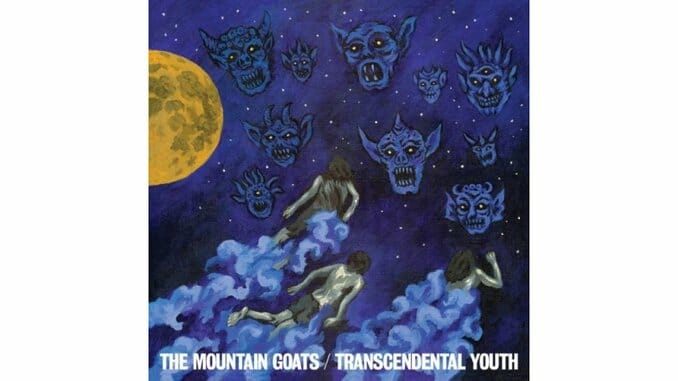

The Mountain Goats: Transcendental Youth

John Darnielle and his Mountain Goats have frequently been at their best while capturing characters in dark situations, usually struggling to get through. Darnielle’s direct lyrics can pinpoint an emotion without limiting the utility of sharing that experience. On Transcendental Youth, the band takes us through a series of trials, flickering a light in a pursuit of something more. The album doesn’t match the group’s best output, but it’s a strong and occasionally stunning entry.

The album offers plenty of splendid moments. The spare, piano-led “White Cedar,” drawing on a symbol of eternal life or endurance, provides a memorable portrait of spiritual fortitude. The singer’s epiphanic experience not only changes him, but it grows in strength, allowing him to take action (“forge my armor”) even as he practices patience for an inevitable change.

“Spent Gladiator 2” manages to sound both ominous and encouraging. The singer’s cynicism provides the basis for, rather than the undercutting of, the song’s hope. The evocative imagery (“a village on the steppe about to get collectivized” or “a bloody-knuckled gunman still stationed on the beach”) grounds the song in specific brutalities that enable not just passive resistance, but defiant assertion, like the suggestion to “spit some blood at the camera.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-