The Songs That Bind: Field Medic

A series where songwriters talk about two songs that changed their lives: one of their own and someone else’s.

In my time as a music writer, I’ve had the chance to share communities and spaces with some of the very best artists in the world. I hold that privilege close and will never take it for granted. Nine times out of 10, I’m interviewing someone about their music because it has, in some form or another, changed my life. That’s why we do this, right? Being someone who has spent so many days devoted to the forever-expanding landscape of music, I don’t shy away from telling someone that a song they wrote changed my life. We deserve to tell our heroes that they’ve made tumbling through this world even the slightest bit easier.

But I wanted to flip the script and call up some good friends and favorite songwriters and get the scoop on the songs they hold closest to their hearts. In the series’ third installment, I spent some time with Kevin Patrick Sullivan—aka Field Medic. This time around, Kevin opted to finesse my system by picking three songs in total. I’ll allow it, but just this once.

I met Kevin for the first time some years ago after a gig at Mahall’s in Lakewood, Ohio in 2019. My partner at the time—our “song” was “OTL” and, for our second anniversary, we took a trip up to Cleveland from our college campus to watch Field Medic open for Beach Bunny, hoping to hear that one beautiful tune. And, of course, Kevin played it—but not before I sent him a DM on Instagram asking if it would be in the setlist. Fast-forward across the pandemic, and Kevin is putting out his “big budget” Field Medic album, grow your hair long if you’re wanting to see something that you can change. I was still freelancing, still hoping that an editor will take a chance on me. I’m already in this mode where, if I can help it, I’m only writing about musicians I adore. I have to profile Field Medic. And Paste was, at the time, gracious enough to give me a shot doing so.

Now, I’m lucky enough to call Kevin a good friend who I can hit up for anything, be it talking about tattoo regrets or shooting the shit about vintage Dale Earnhardt shirts. The world he’s created with Field Medic is one that is vulnerable, nuanced and gloomy—all in ways that make our own maladies a bit more palatable. Listening to a record like Songs From the Sunroom or Floral Prince is like excavating bad decisions until a core clarity is revealed. I love Kevin for that, for how the road to recovery is not a crystallized destination in his work, but an active practice that is never perfect. When I was formulating the basis for this series, I knew he would be a guest on it—once he announced his new album, light is gone 2, it was just a matter of when.

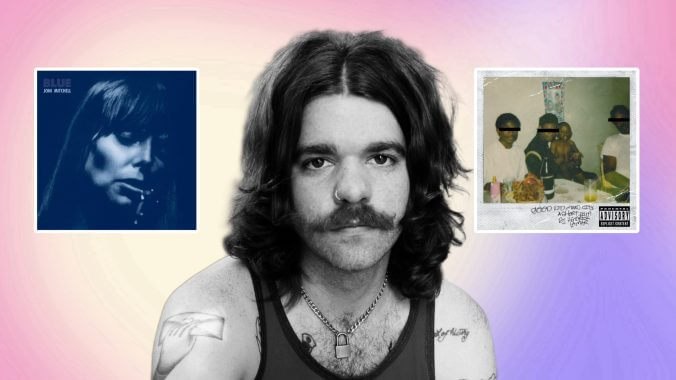

For chapter three of The Songs That Bind, Kevin talks about Joni Mitchell’s “River,” from her 1971 album Blue and Kendrick Lamar’s “m.A.A.d city,” from his 2012 album good kid, m.A.A.d city—as well as his own tune, “p e g a s u s t h o t z.”

You can catch up on our previous two installments of The Songs That Bind here and here.

Joni Mitchell: “River” / Kendrick Lamar: “m.A.A.d city”

When I was thinking about songs that really impacted me, it was these two songs in particular. It was this vocal style, because Joni Mitchell’s music is all very raw. I would say the whole album, Blue, was very inspirational, but “River,” the very last time she says “skate away on,” her voice doesn’t quite crack, but it’s very imperfect. I was so moved by that, and the whole record. But, in that one moment, I realized that the imperfection of the vocal is part of what made it so good. At the time, I was still recording with my old band and we were trying to make “real studio-ready music” or whatever the fuck. My voice cracked all the time, and hearing Joni do that felt very liberating. And, of course, among listening to Townes Van Zandt and Bob Dylan and all of these other ‘60s, ‘70s artists that record live—just noticing that what I actually found appealing about their music was the rawness. Then, somewhere around that time, good kid, m.A.A.d city came out. And then I heard “m.A.A.d city,” where Kendrick Lamar’s voice is super cracking and very emotive for that same reason. Even though the songs are obviously very different, just hearing Kendrick do that to an even more extreme degree than Joni Mitchell—or anyone else that has a little voice crack here and there—I was just like, “Dude, this is sick. This sounds so cool and raw.” Once again, I felt empowered to not be so worried about vocal inconsistencies in my own recording. The thing that changed everything, oddly enough, was some amalgamation of those two songs. I remember, very specifically, having a moment with those two songs somewhere in the span of a year or so—and something clicking in my head and realizing that a raw vocal is chill.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-