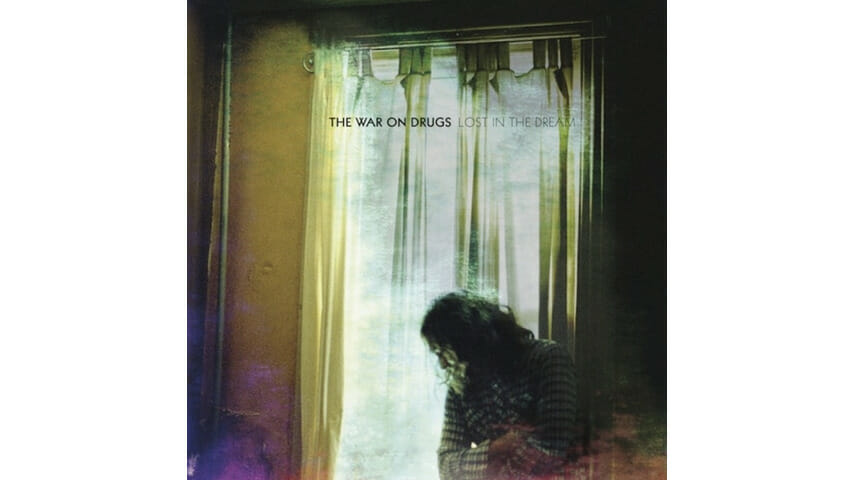

The War on Drugs: Lost in the Dream

I wasn’t sure I needed an album like Lost in the Dream until I heard it. Even then, it took a few listens before I could articulate why it scans the way it does: Wistful but not resigned, invigorated but not wide-awake. As its title suggests, Lost in the Dream often trades in gaseous, impressionistic hues, and a cavalry of affected guitar, synth, lap steel, sax, harmonica and piano tracks gel into luminescent aural sunsets at several points throughout the album. These ambient drifts bookend Adam Granduciel’s tender songs, the lyrics of which also tend to reveal themselves in refracted ways. Indeed, it can be difficult to discern more than a handful of lines in succession—Granduciel’s feathery, mostly reserved delivery sees to this, as well as the tonnage of reverb baked into the mix—but listeners can’t miss the sense of melancholy and anxiety woven into nearly every second of Lost’s hour-plus run-time. “Am I alone here, living in darkness?” he asks on “Eyes to the Wind,” his questioning telling all in a handful of words.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-