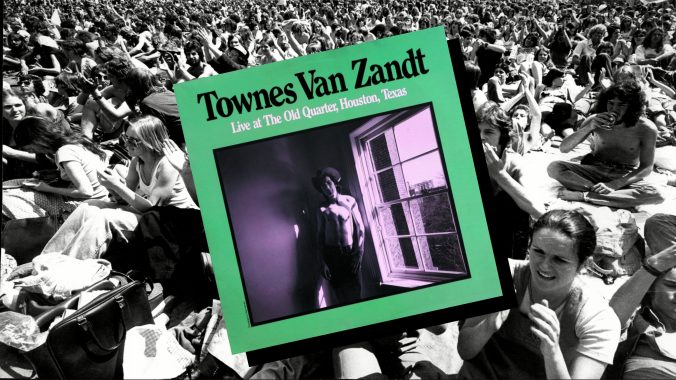

Time Capsule: Townes Van Zandt, Live at the Old Quarter, Houston, Texas

Every Saturday, Paste will be revisiting albums that came out before the magazine was founded in July 2002 and assessing its current cultural relevance. This week, we’re looking at Townes Van Zandt’s indelible live album full of songs of gratefulness and resignation, a preservation of the songwriter just as we should remember him.

Photo by David Thorpe/ANL/Shutterstock

For many years, the name Townes Van Zandt acted like a secret password. Simply name-dropping the late Texas troubadour initiated one into a small posse of music nerds, outlaw country purists and admirers who may have even cried into their beer while listening to Van Zandt at a dive bar decades ago. That all changed with the rise of streaming platforms, the influence of music blogs and a concerted effort by labels such as Fat Possum Records to keep the cult songwriter’s catalog in circulation. Suddenly, it became commonplace to find a “Townes Van Zandt” divider in record store bins or one of his LPs tucked inside a milk crate housing a dorm room vinyl collection. That’s no small leap for an artist whose music could prove notoriously difficult to track down during much of his own lifetime.

Live at the Old Quarter, Houston, Texas endures as one of several Townes Van Zandt records to have received renewed interest and reached new audiences in recent years. It’s by no means the most accessible boot-dip into the deep trough that is Van Zandt’s silo of songs. Recorded across a five-night stretch at the small Houston watering hole in July 1973, the sprawling double-live album collects 26 songs and spans more than 90 minutes with zero smoke breaks. As stripped-down as the shirtless photo of Van Zandt that adorns the album’s front sleeve, Live at the Old Quarter remains the late songwriter’s most intimate and revealing affair. It’s a time capsule that preserves the mercurial artist scratching at the heights of his considerable powers; documents a rich tapestry and tradition of Texas music; and suggests a welcome alternative to the dominant narrative of Townes Van Zandt as primarily a tragic figure.

Van Zandt’s residency at the Old Quarter features him alone on stage with only a guitar and a saddlebag of what would become several of his signature songs. It’s a far cry from the painful overproduction that plagued many of the artist’s earliest studio recordings. For instance, the original title-track cut of “For the Sake of the Song” from 1968’s debut echoes like Van Zandt singing into a tin can at the bottom of the Grand Canyon during a howling wind. On Old Quarter, however, we can hear all the nuances in Van Zandt’s unconventional country voice—the tenderness, confusion and resignation—as he plucks gently and considers how to be there for a lover. Likewise, Van Zandt had already failed twice on studio albums to do justice to “Tecumseh Valley,” his tragic tale of a coal miner’s daughter. Here, he finally conjures both the heartbreaking tone and appropriate pacing that demand attention be paid to the plight of a fallen woman ignored by society. Both of these performances are definitive takes on essential songs in Van Zandt’s oeuvre.

In fact, most of Van Zandt’s material translates remarkably well to such an intimate setting. Our Mother the Mountain’s “Kathleen” loses none of its bleakness or mystical nature in translation to the stage, the room’s hushed quiet enveloping Van Zandt’s foreboding voice much as the eerie accompaniment does on the studio recording. “Waiting ‘Round to Die” finds its restless stride towards the nearest exit even with slowed playing and no percussion. Similarly, the wicked cardroom parable of “Mr. Mudd & Mr. Gold” gains a head of steam purely off the strength of Van Zandt’s mesmerizing phrasing. And the “poet tears” of “Tower Song” transform the Old Quarter from a cowboy bar to a poetry reading, as the songwriter gently reflects on life’s contradicting and fleeting nature. It’s a credit to Van Zandt’s powers as a performer and experience on the road that all of this somehow goes down like a mug to be nursed across an evening rather than a row of random shots that leaves one worse for wear.

Not many live albums owe much to the actual venue and audience featured on the recording. That’s not the case at all with Live at the Old Quarter. Credit Earl Willis, the album’s producer and engineer, for a deft hand that preserves the feel of Van Zandt captivating a famously fickle audience across five sweltering, sold-out nights in Houston with a broken air conditioner. Decisions to leave in announcements about cigarette machines, Van Zandt’s own banter, and the sounds of patrons (minus a few broken glasses) make for an unlikely artifact documenting not only the strange crossroads of hippy and cowboy culture found at the Old Quarter, but also the early ‘70s Texas music scene at-large.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-