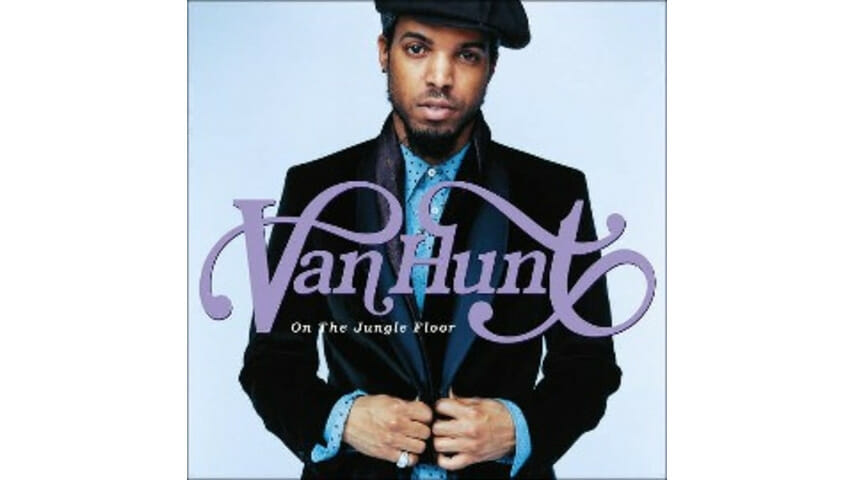

Van Hunt – On the Jungle Floor

Van Hunt blends funk, rock and R&B into soul panopticon with pop appeal

The slick, monochromatic R&B dominating today’s charts bears little resemblance to the supple, sonically diverse music minted by the Isley Brothers, Marvin Gaye and Al Green. Contemporary R&B, with its rigidly booming beats, is indistinguishable from rap until the vocals enter. This is partly a matter of pragmatism—after all, the perfunctory rap cameo is a staple of the genre. But the sensitive ladies’ man with a knack for tasteful innuendo is a dying breed; R&B slants ever more toward giddy materialism and belligerent sexuality. Terse, repetitive catchphrases engineered to lodge stubbornly in the brain get more play than languidly unfurling devotional narratives. The “rhythm” aspect is left intact, turbocharged even. But the “blues,” those ragged jolts of pure feeling, are largely suffocated by glossy digital production.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-