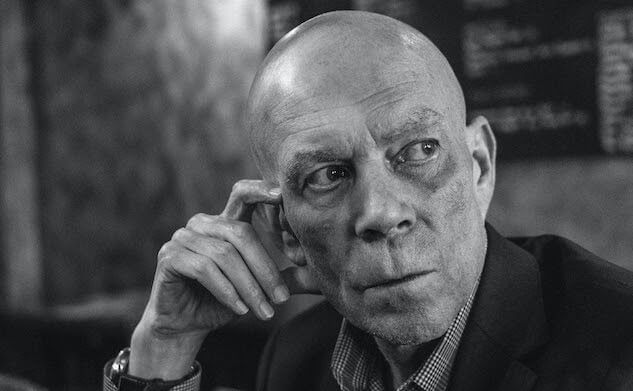

Vince Clarke: Reluctant Solo Artist

Clarke takes a break from his work with his long-running pop group Erasure to explore the possibilities of Eurorack synths.

Vince Clarke had no intention of releasing a solo album. That, perhaps, is not a shock when taking into account that the 63-year-old has never put out any music on his own. Since 1980, Clarke has worked entirely in collaboration, starting as an early member of Depeche Mode through to his nearly 40 year tenure as one half of synthpop duo Erasure. And when he played some of the material he had been messing around with during COVID lockdown using his small array of Eurorack modules — self-contained synthesizers that use dials, sliders and patch cords to manipulate their sound rather than using a keyboard — to the folks at his label Mute, he was shocked to find that they loved it.

“They came back to me and said that they would like to make it into a record,” Clarke said. “I mean, it wasn’t the intention. The intention was just to keep busy.”

It’s not difficult to hear what attracted the folks at Mute to the tracks that would eventually make up Songs of Silence. Restricting himself to setting each piece in a single key and only creating sounds with Eurorack, Clarke developed a series of mood pieces with each one glowing from within as if energized by a core of molten rock or radioactive material. And he augments his experiments perfectly with the addition of some cello, vocals and, on “Blackleg,” a moving sample of a recording of a mid-19th century folk song. To call it ambient would be a disservice to the energy and discord that defines many of these songs.

Ahead of his first ever solo performance this coming Friday November 17th at LSE, London, Clarke spoke with Paste from his home in New York City. The conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Paste: Was it only during the pandemic that you started messing around with Eurorack or is that something that had been part of your arsenal before?

Vince Clarke: I had the Eurorack stuff for a while, but never really delved into it. I never really explored it properly. This was kind of an excuse to do that. I spent a lot of time watching YouTube tutorials of various modules, which I love. I love watching tutorials. I mean, I still don’t really understand the system fully, but that’s when I started to get to grips with it.

How many modules do you think you have at this point? I know you’re a big collector of synths.

Well, I have a big collection of synthesizers, but my Eurorack system is quite modest. Just about two racks of stuff.

You set limitations on the music by making every song center around one note. Does that mean you restricted yourself to the number of modules you were playing with for this tracks?

No, there was no limitation on the modules I was using because, as I say, I was not familiar with all of them. The limitations that I put on making the songs was really more to do with the idea of being able to create a texture or a soundscape without relying on chord changes in the traditional kind of verse / chorus sense. The challenge for me was to really work out how you could make an instrumental interesting because it’s not something I’ve ever really done before.

How did you know when a piece was at its natural conclusion? Was that something that came easily or did that take some trial and error to figure that out?

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-