Wilco Fall Short of Their Best on Cousin

Despite sublime moments, the band’s 13th LP is underwhelming

Jeff Tweedy laid out his approach to crafting lyrics in his entertaining 2020 book How to Write One Song, an instructional manual of sorts. Among other advice, the Wilco frontman suggested making a list of words, connecting the nouns and verbs that don’t seem to naturally fit together to see what images or feelings they evoke, and then following where they lead. Another idea he employs is rearranging something he’s been working on by literally cutting it up and piecing it back together in a new order to see what associations suggest themselves. If those strategies have helped keep Wilco among the most restlessly evolving bands of the past few decades, they prove underwhelming on the group’s latest.

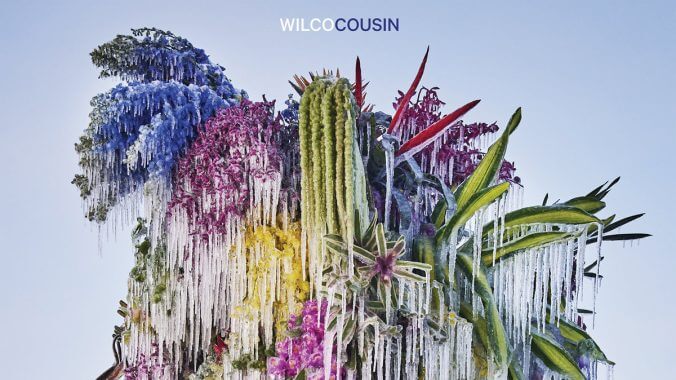

Cousin is Wilco’s 13th studio album, and the first one on which the band hasn’t gotten a production credit. That goes to Cate Le Bon this time, though there’s little on Cousin that suggests her input. Mostly, it sounds like a latter-day Wilco album: Tweedy’s murmured vocals on muted songs that give the impression the band is trying not to awaken someone sleeping nearby. This being Wilco, the musicianship throughout is virtuosic, but rarely showy, and many of these 10 songs feature artful instrumental touches: Glenn Kotche’s heartbeat drum fills on opener “Infinite Surprise,” or John Stirratt’s active bassline roaming over a shifting meter on the title track.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-