Unions, Affirmative Action, More: 6 Supreme Court Rulings that Antonin Scalia Could Have Changed Had He Lived

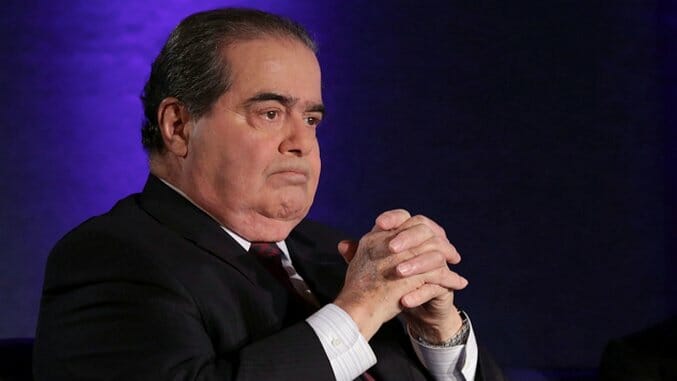

Photo by Alex Wong/Getty

Legendary Justice Antonin Scalia died on February 13th, right in the middle of a session of the highest Court in the land. Scalia was a conservative intellectual giant, providing millions with examples of the bedrock of constitutionalism – where the constitution is interpreted literally without much or any care for the nuances of the modern era. His intelligence and breadth of knowledge were unimpeachable. Whatever your politics, you have to acknowledge that Scalia was a unique and at least somewhat valuable voice on the Court. If you disagree, take it up with the notorious RBG. By her own admission, Ruth Bader Ginsburg was “best buddies” with the late justice.

That said, there is also no doubt that Antonin Scalia loved the sound of his own voice, and straddled the line of judge and politician closer than any justice in the modern era. His ultra-constitutionalist stance certainly wavered when it came into contact with Republican priorities, as Jon Stewart once brilliantly demonstrated.

Scalia’s death may be more consequential to the future of this country than Barack Obama’s reelection. Here are six cases decided by one vote that are emblematic of where we are and where we may be headed.

Quick side note: Big thanks to the team at SCOTUSBlog for informing the bulk of this research.

1. Hawkins v. Community Bank of Raymore

Ruling: 4-4 – The lower court’s decision was affirmed in an equally divided vote that spouses who guarantee commercial loans are not “applicants” under the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA).

At first glance, this looks like yet another bank squishing the little guy, but it’s really about sloppy work by the legislature. The Community Bank of Raymore demanded guarantees from the wives of applicants who wanted a loan to build a residential subdivision. The dispute stems from the text of ECOA, where it outlaws discrimination on the basis of marital status and defines an “applicant” as “any person who applies to a creditor directly for an extension, renewal, or continuation of credit.” Scalia was very active during the hearing of this case, as Ronald Mann of SCOTUSblog detailed:

Justice Antonin Scalia asked whether “the agency can make that up”? He went on to offer a hypothetical suggesting that he had written a recommendation to a law school, asking that it admit a young woman, putting his “reputation on the line on her behalf. Am I an applicant to the law school? Would anybody use the English language that way?”

The justices proposed various other hypotheticals that tested the shaky ground this portion of ECOA stands on. Even though the bank is using the word “applicant” to describe both the applicant and his wife, the wife is really acting more as a co-signer or a guarantor. Affirming that an applicant’s wife qualifies as an “applicant” under ECOA raises some tricky questions about what amount of control the spouse has over the loan. Given Scalia’s skepticism of its use of the English language during the arguments and his aversion to most government, it seems unlikely that he would have ruled against the lower court’s decision.

2. Dollar General Corporation v. Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians

Ruling: 4-4 – The issue at hand is whether Native American tribal courts have jurisdiction over non-Native Americans for tort claims. This is a wonkish case buried in the history of the Court which has massive implications for Native American sovereignty. The tribe and a significant number of amici including the United States contend this is settled law while Dollar General claims otherwise.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-