Let the Landlines Ring: One Easy Trick to Make Your Poll Results Pop

If nothing good happens after 2 A.M., then by inversion’s logic, at 3 P.M., even if one was eavesdropping on a retiree at an Arizona golf course mere weeks after Trump’s inauguration, some good can arise. And thanks to some chance positioning at the driving range, and my strained hearing efforts, on that fateful 2017 day I learned two things: that Bill O’Reilly had a new book out called Old School, and that in this fellow’s estimation it had a “really good” section early on, in which one could determine, by way of a brief but scientifically rigorous quiz, whether one were “Old School” or a “snowflake.”

For a few weeks I would tell this story and think little of it, a brief oasis of silliness in that strange era when the biggest issue was finding time to March for Science. But then, during one lazy afternoon when I was neglecting my work, I had an epiphany: If this quiz were in the introduction, or close to it, then thanks to the previewing magic of Google books, I could probably take it myself. Thirty seconds later, I learned the comedic power of “landline.”

Suffice to say, the quiz is a disaster. Across much of the preamble and its five questions, it’s equal parts offensive and unsurprising, sprinting through a paint-by-numbers display of transphobia, jingoism, and basic aversion to human difference that any midlife hack comedian could provide. For the average Fox News viewer, it is perhaps the closest thing they have to soul food.

I think “landline” is different. All of these questions are misguided, but “landline” is such a targeted but impotent jab at the soft millennial underbelly, it always makes me laugh. I can’t fathom that something this innocuous is one of the Old School crowd’s five biggest grievances, let alone batting first in the lineup, and then I realize that there are nearly two hundred more pages of presumably lesser gripes. Its placement in the book provides insight into the collective psyche of this population—anything representing change, no matter how much more powerful and dynamic and accessible, must be bad—but it also offers the left rhetorical ammunition against that generation. If conservatives can deem any and all opponents “snowflakes,” then in turn I suggest we term them “landlines”: dusty, obsolete, and far more dependent on government infrastructure than they’d like to admit.

Outside of O’Reilly’s impotent polemic, though, there is one context in which landlines still play any outsized role of importance: political polling. As phone technology has developed, not just through the proliferation of mobile phones but also caller ID, silent mode, and the growth of telemarketers, response rates have plummeted. By the second half of 2018, well over half (57.1%) of American homes possessed only wireless phones; for young adults, that proportion was north of three-fourths. And yet, a survey that no one answers is a bad survey; as long as people need to answer the phone, landlines will play an important role for pollsters, for better or for worse.

This article by Hassen Morad details the diminished yet continued significance of landlines in polling: Across 71 different kinds of polls, landlines accounted for about a quarter of all survey respondents. As Morad documents, the plurality of polls reach participants through both landlines and cell phones.

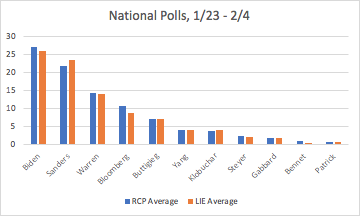

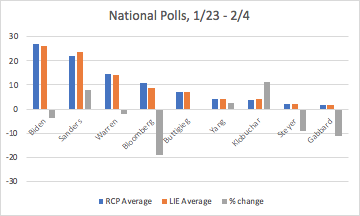

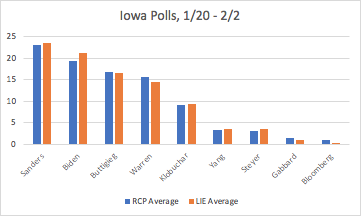

Today, there are polls of all shapes and sizes. There are neat trendlines, visualizations of the range of uncertainty conveyed by margins of error; there are nuanced grades of polls, mincing distinctions made between those targeting registered voters and likely voters. Even if no one knows what to do with any of it, we are in a golden age of data. But to my knowledge, so far no one has tried to answer this rather pressing question: Who’s winning the landline vote?

That is, until now.

Introducing…The Landline-Indexed Evaluator (LIE)

The LIE is calculated thusly:

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-