How Should We Write About Trump Voters? Answer: Don’t.

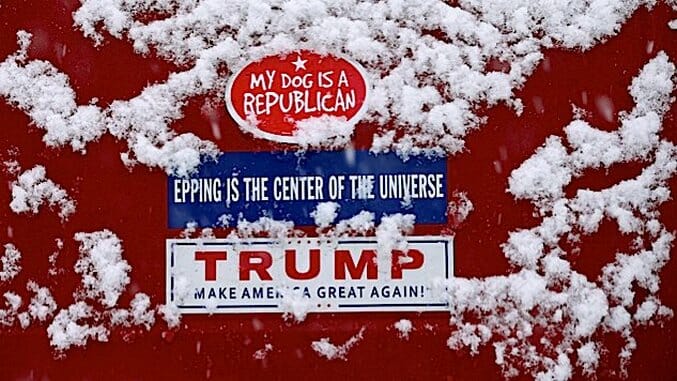

Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty

Since the 2016 election, national media outlets have been on a constant expedition in pursuit of that most elusive of specimens: Any of the nearly 63 million Americans who voted for Donald Trump. Braving such far-flung locales as Staten Island, reporters have sought evidence that Republican voters indeed voted for a Republican president. So far, the consensus appears to be that electing Donald Trump required someone to like his politics enough to vote for him.

Many of the pieces searching for the reasons for Trump’s rise and stubborn popularity among GOP voters defy satire. These are boom times for maudlin amateur sociology. Anywhere that codes as “white” and/or “rural” must now be rediscovered as if it were a lost civilization once swallowed by the sands of Obergefell v. Hodges. Half the time, the takes are just wrong. As Alex Nichols writes, pickup trucks, a cherished symbol of country life to urban media commentators, are in fact expensive and a staple of the white upper-middle-class: “Anyone with roots in the suburbs can testify that many a cul-de-sac is now lined with beefed-up Rams and Silverados used solely to commute to air-conditioned office jobs. What out-of-touch columnists consider bona-fide symbols of working-class authenticity are often just the hallmarks of well-off white suburbanites.”

Well-off white suburbanites are Trump’s true base, as they’ve been the base of every Republican president since at least Nixon. That the Republican Party has loyal voters and can rally them for even a controversial candidate appears to be a truth that eludes New York Times columnists. Still, talking to some Trump voters might indeed yield insights. The broad left-of-center may or may not be taking the right lessons from voters who went from Obama to Trump, for example, but it’s worth asking why they did.

Yet the most compelling anecdotes about the election have come from reporting about those who didn’t turn out at all. More than eight months after its publication, a New York Times story titled “Many in a Milwaukee Neighborhood Didn’t Vote—and Don’t Regret It” might still be the best source of searing quotes about the Hillary Clinton campaign’s failures in key Rust Belt states. It’s hard to argue when a barber who twice voted for Obama and has struggled to find workable health insurance pairs his declaration that he didn’t vote with the line, “Ain’t none of this been working.” Maybe someone should ask him what he thinks would work.

Or we could ask why a dude in rural California is looking soulfully out his window.

I feel bad for white people like they can’t even look forlornly out a window without the New York Times showing up and asking them questions

— JuanPa (@jpbrammer) July 5, 2017

“California’s Far North Deplores ‘Tyranny’ of the Urban Majority” leads with a baleful photo of a megachurch pastor in the shadow of three stuffed deer heads, helpfully captioned, “Eric Johnson at Bethel Church in Redding, Calif., not the California of ‘Baywatch’ fame.” The piece goes on to cite a movement to establish a breakaway state called Jefferson and the vague grievances of a retired pilot who can afford what appears to be a hobby ranch full of horses and bison. Halfway through, we get this stunning line: “But perhaps nowhere else in California is the alienation felt more keenly than in the far north, an arresting panorama of fields filled with wildflowers and depopulated one-street towns that have never recovered from the gold rush.” The biggest California gold rush ended in 1855. If Trump wins a second term, maybe reporters will get around to asking Atlanta residents whether anything has changed since their city was burned down by General Sherman.

In a recent issue of The New Yorker, red voters in a blue state get the longform treatment. Peter Hessler reports from Grand Junction, Colorado, a boom-and-bust energy industry city on the far side of the mountains from the thriving Denver area. The headline reads, “How Trump is Transforming Rural America.” Even though Hessler is as circumspect and shy of caricature as you’d expect from a writer who’s done incisive dispatches about places as different as China, Egypt, and the United Kingdom, we know from the get-go that this will be a voyage of discovery. It’s not enough for Trump to make sense within existing partisan logic; he must be the harbinger of something new and angry.

Hessler paints a picture of an energized local GOP base that embraced Trump’s irreverence and sense of grievance. Western Slope Trump supporters even replicated the candidate’s sparring with the media in a battle with the local paper that got national attention. The piece opens with a portrait of Karen Kulp, a nurse who grew up as a doomsday Bircher, then became culturally more liberal, and finally became a political activist in the 2016 election. The punch line is that she helped found a local group of Trump supporters, despite a narrative arc that bore all the hallmarks of a Boomer Clintonista. Hessler’s opening gambit is to defy expectation while still landing us back in the headspace of the Trump Voter.

Grand Junction perfectly fits the established Trumpville profile. Legacy reliance on a declining industry (oil and natural gas extraction), a predominantly white population, cultural conservatism, blue-collar self-image, an apparent sense of grievance and betrayal at the prosperity, snobbery, and statewide political power of a wealthier urban populace not very far away in Denver and Boulder. Crime is up and schools are in trouble. Hessler sets out to chart the ways in which the political currents of Grand Junction dovetail with the real and imagined landscape of diehard Trump supporters throughout the country. It makes sense that he’d focus mostly on activists and local party operatives. If the thesis is that Trumpism represents a distinctive, transformative movement, the people driving it on the ground in a place like Grand Junction are the ones creating change.

Matt Patterson gets more ink in Hessler’s piece than anyone. A working-class Grand Junction boy by birth, Patterson dropped out of high school, became a successful magician, and then studied classics at Columbia after a car accident destroyed his magic career. He has since worked for conservative nonprofits, with a special focus on anti-union activism. Though he now lives in D.C., he spent the election in Grand Junction organizing for Trump. Patterson comes across as a charismatic shape-shifter: “[At] times he dresses with the flair of a goth: black T-shirt, leather bracelet studded with skulls, silver ring decorated with a flying bat. Sometimes he paints his fingernails black. These accessories vanish when it’s time to interact with factory workers, voters, or Republicans in Middle America.” Hessler’s descriptions of Patterson fit with the essay’s basic strategies to avoid falling into the bald clichés of most Trump Voter pieces: Elaborate apparent contradictions, emphasize that “I learned to suspend any customary assumptions regarding political identity,” and then note that you met a “hippieish” guy with a ponytail who voted for Trump.

Patterson’s importance to the piece is that he was an early Trump supporter who happens to be from Grand Junction and worked there during the campaign. It doesn’t at all follow that his existence demonstrates that Trump is “transforming” much of anything. Patterson is a slick Ivy League alumnus who has worked with Grover Norquist. We have a term for people like Matt Patterson: party hacks. And everywhere party hacks go, they cultivate eager local volunteers like Karen Kulp. If Trump innovated anything in Grand Junction, it was getting his volunteers to pay him for the privilege of helping out. As Kulp memorably says of the Inauguration Day “DeploraBall” she helped organize, “Every shirt you see here tonight, I bought.” This is the only genuinely impressive feat of political salesmanship recorded in Hessler’s piece.

A necessary conceit of the Trump Voter piece is that it must be interesting that someone voted for Trump. Was it interesting when people voted for Mitt Romney or Gerald Ford? Was it a metaphor for the tragedies of hardscrabble white America? No, presumably because those guys are a lot duller than Trump. No argument there. But the boring fact underlying Trump’s victory and now his presidency is that he’s a servant of very familiar forces.

The GOP agenda under Trump is basically what it would have been under Marco Rubio or Jeb Bush, only with more chaotic news cycles and instantly lower approval ratings. The Matt Pattersons of the world didn’t create this reality—that would be the Charles Kochs and Sheldon Adelsons—but they do know how to keep it going. One way to keep the oligarchic agenda humming along is to give it an aesthetic of rugged authenticity. Trump does that very well, and he gets a lot of media help. It may be impossible to write a Trump Voter piece, however careful, that doesn’t end up doing the work of making age-old robber baron politics look like an Andrew Wyeth painting come to life. We should probably stop trying.

There are lots of worthwhile things we could learn about life in Redding, California or rural Colorado or anywhere else with especially reactionary politics. Everyone quoted in Hessler’s piece had something to say about their home. The frustrating thing about Trump Voter pieces is not that they reduce whole regions to politics; it’s that they reduce those politics to Trump. If voting for Trump was such a convulsive act in Grand Junction, then is it also true that if Hillary Clinton were president, life there would be noticeably different? Trump Voter pieces mostly don’t seem interested in that kind of question. There might be hand-waves at NAFTA and industrial decay and opiates and wealth being sucked into big cities. Why is any of that happening? Who benefits? Can we do anything about it? I guess we could look ruefully out our windows at the world we share with Trump Voters.