Everybody Run! (For Office)

Everybody should want to rule the world

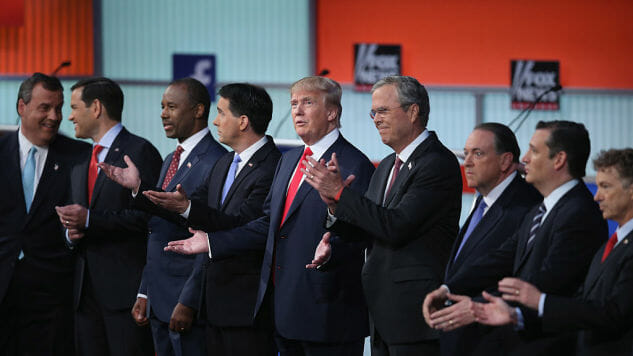

Scott Olson / Staff

Why don’t we have better people running for office?

This is a simple question, but unlike most simple questions, the Internet has been unable to answer it for me, no matter how many times I try to talk to my laptop screen. So the dilemma remains: Why?

The Prophet Sanders made this a cornerstone of his campaign, and it became a major plank of his post-Convention program. According to the Burlington Free Press, Sanders told the world on June 16, 2016:

“We need new blood in the political process, and you are that new blood,” Sanders said in a live video address on Thursday night, his first major speech following the final Democratic primary contest earlier in the week. Sanders, who began his elected career as mayor of Burlington, argued that thousands of supporters should join local institutions such as city councils and school boards that make “enormously important decisions.” The campaign has created a website to help like-minded people run for office. … “The political revolution means much more than fighting for our ideals at the Democratic National Convention and defeating Donald Trump,” Sanders said. “It means that, at every level, we continue the fight to make our society a nation of economic, social, racial and environmental justice.”

He provided a page for it on his homepage. He wasn’t the first to think about it, either. There’s a site where you can search for open positions in your area.

Slate’s Osita Nwanevu wrote about it back in January, in an article literally titled “How to Run for Office”:

The moment does not demand that you run for Congress, although many of you should. There are, by one count, 519,682 elective offices in the United States, each with a role to play in mitigating the trickle-down effects of hegemonic Republican governance on vulnerable communities in the Trump era. Many of these offices are already held by admirable public servants. Many are not. And every election, many of those who ought to be replaced run unopposed. About one-third of state legislative races in 2012 featured a single candidate running unopposed, most of them incumbents. This was not because those candidates were the only qualified people available or because they were singularly excellent at their jobs. This was not because a third of them were unbeatable. People who could have run—people who should have run—did not.

Long story short, over thirty politicians have been elected in these United States, and a considerable proportion of them are probably what our beautiful forefathers called “reptile kings.” The modern term for them would be questionable. Many of them are the fleshy extensions of major lobbying interests. Some of them are actually non-imaginary monsters. Still others are actually zombies, who have the appearance of life but not the biological reality of vitality. Again, the conundrum stands: why aren’t there better people running for the big chairs?

THE OSSOFF PROBLEM

Jon Ossoff, Mr. “Consolidate All Federal Data Centers,” was the latest example of the puzzling talent drought. A latent climate of middling lukewarm affirmation hovered around him. His domestic priorities were the careful hunting of Panera bread, and he would have killed universal healthcare for a pleasing mention in the Cleveland newspapers. The wheezing, unreasoning centrist impulse, near to death, took possession of him, and twisted his chances like a screwdriver. Had he been tutored in boneless action, or was it his own natural habit? Hard to say. His importance swelled as his script was thinned. Crystals have more healing power than Jon Ossoff, but for a month he was Excalibur in the hands every gala Democrat west of the Rockies and East of the Appalachia. Next to Karen Handel, he was Pericles. Next to Greg Gianforte, both were the peers of Gandhi. Why are these our choices?

The Dems, and for that matter, the GOP, gives us scrubs. Is this what we’re reduced to? Having court-ordered parents to pass our laws, govern our roads, and rate our TV? Most of us go through at least twelve different hairstyles on our headlong rush to death. Some of them are assured to be unterrible. Most of us are guaranteed to drunkenly punch one person into unconsciousness at least once in our lives. That’s a victory for half of the people involved. Why can’t that ratio obtain in our governance? Why can’t we have the same consistency in our elected representatives?

Let’s focus on Congress, since that’s where the power lies. That distinguished body has a 11% approval rating but a 96% incumbent reelection rate.

Detailing the mechanics of reelection—how Congress generally favors incumbents—would be a much longer article. The touching saga of brave lawmakers at sacrificing their prime golfing years to service special interests could inspire a hundred Lifetime stories—or at the very least a dozen self-serving picture-heavy autobiographies with titles like “Glad to Serve” or “A Life of Drive” or “Best versus Blessed” or the occasional “Guns, Grins, God, and Grit” and “Wear a Tie to Work! My Time in Washington.” And even if we consumed such big-hero ballads, we’d still be left the question of why we elect rafts of mediocrities to be our future statues. Why are we stuck with them? What law of nature makes them our keepers?

BREAD

Money, you say. That’s the barrier. Money would be the obvious choice. Cash is the necessity of political life. In a fictionalized version of “America: The Motion Picture,” Money would be a major villain, like mummies were the chief bad guys in our ancestors’ time. Money stops our politicians from having to be normal human beings. It makes political contests into relatively uneventful races until someone hyper-extends their drug use or crazy phrenology beliefs into the media cycle and then there’s an actual race. Money buys Jay-Z the right to do as he pleases, and lucre buys elections.

But there’s a reason money is not the end-all and be-all of politics. Money is there for the right candidate. And the right candidate doesn’t have to be a rigid plank of talking suit or a half-trick pony. If there are good candidates who can put two rhyming sentences together, then there will be funding. Earlier this year, I saw an airman named Sam Ronan run for the chair of the living hell-position of Democratic National Committee Chair. Ronan had literally nothing except a larynx full of good words and an ambulance-sized heart, and he got national attention, of the kind we usually give to Snapchat teens and parody Twitter Accounts from Sam Raimi movies. Ronan didn’t win but he got noticed.

The majority of the Democratic and Republican parties are sympathetic and shocked by the concentration of hideous lameness in their institutions, but can do nothing about it because most of the elected reps are grievous tools, who are mostly there to hold ties and pantsuits up in three-dimensional space and not much else. Like SkyMall, there’s not a lot of quality when you dig down deep enough. Being aware of how reality functions, the rank and file of both parties can recognize non-terrible candidates, or at least functioning human personalities when they see them. Both individuals and organizations hope for anyone who has a chance, anyone who is not part of the same old machine.

CIRCUSES

So, if not money, what? Boundaries, you might say. There are documents to file, you might tell me, paperwork to be authorized, binders of rules to be perused and then thrown against the wall in frustration. And after that, there are all kinds of co-pilots you must have to be a politician: you have to go to this school, you have to have never made any big mistakes, you have to be a go-getter and be the kind of person stand-up comics would never pick on during their set. You’d look at me and say, if you spent your high school playing Yu-Gi-Oh or drinking instead of being on the Student Council, you cannot get to Washington.

To be fair, these barriers exist, just as barriers to being a successful ventriloquist or dog whisperer exist. But they are not as high as you think. Given the kind of people who become politicians in the current Washington—body slammers and narcissists—there doesn’t seem to be a huge personality test that you’d have to pass to run for office. I am sure, but cannot prove, that there are people who get elected to high office who have been ejected from Target and perhaps even Wal-Mart. No clean slate is required, and no resume either. Indeed, the way to elected office is not far from the citizen.

Well then, if it’s not money or cultural barriers, what could it be? Is it the nastiness? Perhaps that’s it. But there’s a curious counterpoint. A significant portion of the American public would like to be famous. Yet it’s difficult to think of an existence which leads one being more widely disliked than becoming a celebrity. No matter how beloved you are, you will still end up being disliked by some set of people—certainly more people than disliked you when you were unknown. Yet who amongst us hasn’t dreamed of being on first names with the Muppets and their celebrated Seventies friends? While nastiness is a major factor, it seems unlikely to be the deciding one.

ON GOOD AUTHORITY

In the end, citizens avoid becoming elected officials for a very simple reason. They don’t think of it, and don’t see themselves that way. Our culture does not encourage involvement in politics. It advocates emotional reactions to politics—rage and annoyance and passion. But that is not the same as involvement. Our society prefers for us to be consumers of politics, not participants. We are informed reverently that politics is for experts.

But this is fantasy. The word “Republic” literally means ‘The public thing.” Humans are social creatures, and are bound by culture and their own nature to be group animals. The only doctor for the salvation of the government is us. Half of the time, our current politicians are bored trillionaires who want a new scope and wider challenges. If they can do it, anyone can.

Why don’t we have better people running for office? Simple. The solution isn’t “better people,” it’s “all the people.” Expertise is not required.

Widespread office-seeking, by every faction of the public, is the best hope of the government. In biology, monocultures are fragile; it is the diverse biosphere which thrives. And Congress, and all of the other offices of state, need every kind of person to fill them. Everybody running is the point of democracy. Politics is not about the hope for a single, charismatic figure emerging from the ether and saving the cause of democracy.

Rather, it is the hope of a network, a team, an alliance of hopes. We don’t need perfect people, we just need people, a wide variety of them, taking a chance and risking the approval of their fellow citizens. Let placards appear in every lawn in America, reading ”[NAME] for [OFFICE].” In this sign, we shall all conquer.