Throwback Thursday: El Salvador vs Honduras (June 26th, 1969)

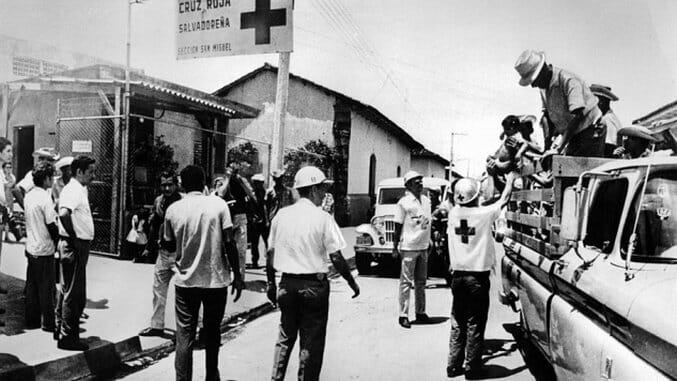

Photo via Hulton Archive

Among those of us who love football, there are some that hold the sport up as something that brings people together. Something that fosters peace and understanding. Something that transcends cultural, national, racial, ethnic, and even gender barriers. That even with the greed and corruption at the highest levels of the sport, football calls out to the better angels of our nature. We’ve written here before about how football can bring out the best of us even in the midst of war.

All this is true. Or, I should say, I choose to believe that this is true.

Yet that power is absolute. And as much as I want to think that football can stop or prevent war, it’s undeniable that it can sometimes inflame as much as it can heal.

This week we look back at the 1969 Football War, and how The Beautiful Game made way for war.

Lest we inadvertently sensationalize history it should be stated: football was not directly responsible for a war between two sovereign nations. It’s part of the story, but just to be clear, no one ordered tanks to be deployed because of the result from a soccer game.

Telling the whole story of the Football War would require a book, but here’s the abridged version:

Honduras is about five times the size of El Salvador by land area, yet in 1969 it’s population was nearly half that of their neighbors’. Salvadorans had been migrating across the border throughout the 20th century in search of work and arable land. As migration continued, Salvadorans and Hondurans were marrying and starting families. By the start of 1969, Salvadoran migrants made up roughly 20% of the population, and almost all of them were poor or working class. Many were squatters on the land they had claimed as their own.

At the time, most of Honduras’ land was held by either a small class of wealthy landowners or by large corporations. If you’re a cynic, or if you hold a dim view of the 1%, you can probably guess what happened next. The landowners were furious about the influx of these campesinos from El Salvador. Several companies and landowning families, led by the United Fruit Company (which has since been absorbed into the Chiquita empire), banded together to form a powerful special interest group called FENAGH and began pressuring the Honduran government to do something about the Salvadoran migrants.

A year after FENAGH was formed, the Honduran government started enforcing a law it had passed a few years prior that allowed for land occupied by Salvadoran migrants to be “reclaimed” and given back to native-born Hondurans. The government crackdown was applied even to Salvadorans who immigrated legally and held legitimate ownership claims to their land. Nearly 300,000 Salvadorans became refugees overnight, with many choosing to go back to El Salvador. Families were broken up and livelihoods were destroyed. It kicked off the start of one of the biggest political crises and humanitarian disasters in the region in the 20th century— and that’s saying something.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-