A Digital Geneva Convention for Cybercrime Will Only Go So Far

Photo by Nicescene / Shutterstock

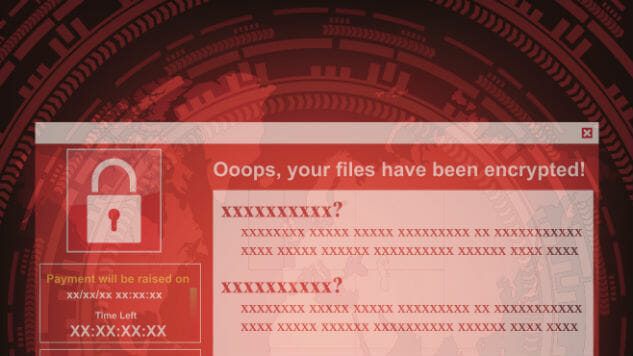

IT departments and cybersecurity professionals are still on tenterhooks after last weekend’s global cyberattack. The WannaCry ransomware wreaked havoc on IT systems around the world from National Health Service hospitals in the UK to car manufacturing plants.

The first wave of attacks was initially stymied by an IT expert in the UK who accidentally discovered the kill switch URL for the ransomware. But by the time Monday morning rolled around, there were renewed fears of infections as people returned to work and booted up their computers.

WannaCry and its fallout has led to a lot of finger pointing. Many of the computers infected were still running Windows XP, which Microsoft no longer supports, but in an unusual move the company issued a patch to relieve the risk.

WannaCry is a vulnerability stemming from code harbored by the NSA—dubbed EternalBlue —but it was ultimately stolen by a hacker group called the Shadow Brokers. This brought the NSA and government spy agencies under scrutiny with Microsoft’s chief legal officer not mincing his words.

Brad Smith said the “stockpiling of vulnerabilities by governments” is a real problem. He also pointed to the WikiLeaks publication of CIA data on hacking tools and methods. If a spy agency or a government holds this sort of data, it is vulnerable to leaking, like any data. Every time such a leak happens, it puts regular people at risk.

“An equivalent scenario with conventional weapons would be the U.S. military having some of its Tomahawk missiles stolen,” said Smith. “And this most recent attack represents a completely unintended but disconcerting link between the two most serious forms of cybersecurity threats in the world today—nation-state action and organized criminal action.”

Smith is vivid with descriptions of and comparisons to traditional warfare and weaponry and repeats a proposal for a so-called Digital Geneva Convention to regulate how governments and spy agencies handle critical vulnerabilities once they’ve been discovered.

Photo by Mark Wilson / Getty Images.

The Geneva Conventions refer to a wide set for rules, first formulated after World War II. The conventions are made up of four treaties and three protocols that impose humanitarian protections during war into international law. It was ratified by 196 countries in 1949.

When we talk about a Digital Geneva Convention, we’re essentially talking about a set of internationally recognized rules for zero-days and web vulnerabilities and how we respond to them.

As it stands there is no coordinated effort quite like this to ensure protections for civilians in the face of cyberattacks. On paper, it sounds like an ideal protocol but would need a lot of work.

In the wake of financially-driven cyberattacks and the growth of nation-state activity, Smith believes tech companies should take on a more proactive role in protecting the regular people (i.e. their customers) from cyber intrusion. He believes that the tech sector are the first responders in this situation and should be a neutral Digital Switzerland that the world can trust with a “100 percent defense and zero percent offense” approach.

The NSA is believed to be the root cause of the WannaCry outbreak last week. Reportedly the vulnerability in Windows systems was detected and maintained, unbeknownst to Microsoft, by the agency. When NSA hacking tools and methods were obtained by a hacker group called the Shadow Brokers, it placed the vulnerability in the hands of evildoers. Of course, depending on who you ask, the NSA would be considered evildoers too.

Under a convention, the NSA would be required to notify Microsoft that it found this bug. This would allow Microsoft to patch it and in theory, last weekend’s mess wouldn’t have happened.

Smith pointed to some practical examples of Microsoft being proactive against alleged nation-state phishing attacks. Its Digital Crimes Unit tracks domains registered using Microsoft trademarks and seeks court orders to alert internet registries about suspicious domain names before they can be used for phishing. Smith claimed that this method has thwarted many attacks including a nation-state plot.

This would be just one component but is a fine example of a coordinated effort. The bigger picture would involve a lot of grunt work for governments in crafting multilateral agreements that bar each other from attacking private companies, civilians, and critical infrastructure.

There has already been some movement in Europe. ENISA, the EU’s cybersecurity agency, and a number of EU member states have established a taskforce to “ensure the security of European citizens and businesses” in response to WannaCry. It is the first cybersecurity cooperation of its kind at an EU level.

Coordination between allies is a little more straightforward but when we consider the supposed hacking capabilities of Russia post-DNC hack, would the Kremlin be so willing to sign up to such a deal?

Furthermore, the latest suspicions around the culprits behind WannaCry have cast an eye on North Korea, which has allegedly carried out notable attacks in the past. The Sony hack of 2014 is the most infamous. The hermit state is certainly not going to sign up to a deal very easily.

So, while the US could hammer out an agreement with say, the EU to alert each other and vendors about vulnerabilities, it won’t adequately address vulnerabilities being weaponized by states like Russia or North Korea or wherever else.

The idea of a Digital Geneva Convention may be very aspirational but better communication between opposing sides is not totally impossible either. In 2015, the US and China made an agreement to not carry out cyberattacks on each other. To go deeper, a convention would also require the establishment of an international independent body to oversee its enforcement and investigate violations. And if a violation does occur, what is the punishment?

Of course, this isn’t to say there aren’t already expansive international agreements on cybersecurity. There is the Wassenaar Arrangement, which governs the international trade of military weaponry and dual-use items, which now includes intrusion software, and NATO has stated that international law applies to cyberspace.

Nor is this the first time that an ambitious new initiative like this has been floated. There have been proposals for Manhattan Project for Cybersecurity. Where the original Manhattan Project developed the US’s first nuclear weapons during World War II, a cyber project would bring together government, academia, and business to develop stronger cyber defense technologies.

Microsoft’s position on WannaCry seems clear and it lays much of the blame at the feet of the NSA but a Washington Post report on Wednesday seemed to contradict the notion that Microsoft was totally in the dark about this vulnerability.

If a Digital Geneva Convention is to work then every party needs to lay their cards on the table.