American Experience‘s The Gilded Age Delivers an Origin Story for Our Own

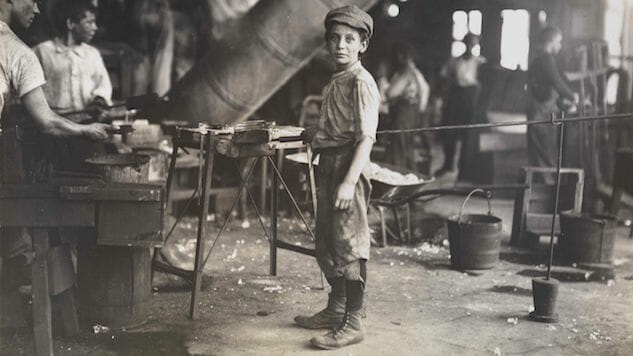

Photo: Courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York

I suspect every generation probably faces a temptation to believe they are the ones on the precipice, the ones at the tipping point, the ones facing things like nothing we’ve ever faced before.

So it’s good to be reminded of our history, because what we’re experiencing mostly has happened before.

The Gilded Age, directed by Sarah Colt, is exactly the kind of documentary that keeps PBS eternally relevant and for which we have always relied on it. It tracks the rise of the great industrial titans of 19th century New York and the development of the original American 1%. As one of the interviewed historians notes, it’s important to remember that “gilded” doesn’t mean “gold.” It’s a veneer, a thin golden coating on another material. She then mentions “the rot underneath,” and while that’s not inherently what the word connotes, there’s certainly plenty of rot to examine in our industrial past and its ramifications for the present.

We follow the trajectories of the storied barons of New York society—Andrew Carnegie’s steel fortune, JP Morgan’s rise to the top of the banking world, the Vanderbilts’ railroad fortune and their (at the time) controversial ascension into elite society. We see how the decadent splendor of a few families was built, often brutally, on the backs of the working class. Via a number of historians and a lot of very cool archival images, the program provides a kind of origin story for questions we’re still asking today. How should the economy work? What is its best relationship to government? Can we concern ourselves with economic growth and economic justice, or is it always one at the expense of the other? Are we indeed one nation in which everyone has the opportunity to thrive, or is there one United States for the extremely wealthy and one for the rest of us?

As New York City became the first American city with a million inhabitants, the economy was booming and jobs were abundant. But the wealth of the people at the top depended on cheap labor, and working-class folks (including children) were expected to work twelve-hour days for very low wages. Henry George inflamed the imaginations of American laborers with his best-selling Progress & Poverty, which condemned the growing economic inequality and put forth the premise that poverty was not due to personal failure but caused by a rigged system. He was nominated as a Labor candidate for mayor of New York. He was defeated, but it was a very close race.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-