Alone, Together: BBC America’s Queers and the Changing Meaning of “Coming Out”

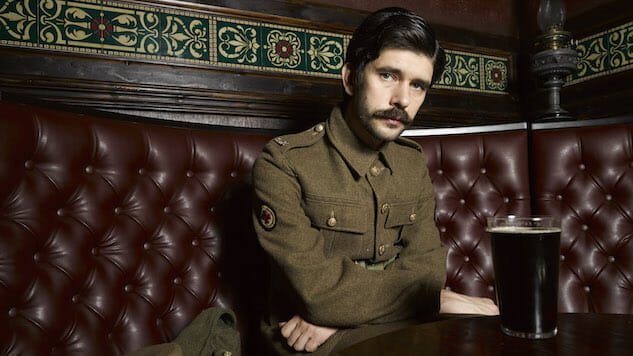

Photo: BBC America

One kisses a hand. One drops a candle. One survives the Blitz. Others perform, protest, even marry: BBC America’s Queers, a series of eight shorts commemorating the 50th anniversary of Britain’s partial decriminalization of sex acts between men, might be described as a collection of comings out, though none evinces interest in formal announcements. For the films set in the earlier part of the twentieth century, in fact, the phrase “I’m gay” remains absent from the language; in its place Queers outlines other forms of communication, clothes and caresses, euphemisms, “a certain liquidity of the eye.” In the context of the series’ historical scope, ranging from the midst of World War I to the near-present, it’s a reminder that “coming out” itself is contingent, that there are many ways for us queers to be seen.

As directed by Sherlock’s Mark Gatiss, this, as much as hiding or passing, is the series’ central theme: With the exception of Jon Bradfield’s “Missing Alice,” which focuses on the wife (Rebecca Front) of a gay man in the 1950s, each of the eight monologues, no more than 20 minutes in length, unspools as if its protagonist were leaning over the table, or spinning around at the bar. The stories are rangy, interrupted by recollections and unexpected detours—to the West Indies, in “Safest Spot in Town” (written by Keith Jarrett and starring Kadiff Kirwan); to the cruising man’s bathroom stall, in “More Anger” (written by Brian Fillis and starring Russell Tovey); to a falafel stand and a companion’s flat, in “A Grand Day Out” (written by Michael Dennis and starring Fionn Whitehead). But the aesthetic is simple, deceptively so. I tried to imagine any one of the films interrupting the network’s regularly scheduled programming, confiding in the viewer as one might an old friend, and their seeming chasteness disappeared: Imagine tuning in for the World Service and finding a man in World War II-era London describing his one-night stand “tast[ing] of the suburbs, like he had a Hammsersmith wife waiting for him at the back of his throat.”

It’s these poetic intimacies that set Queers apart, underscored by the actors’ closeness: When Gemma Whelan (Game of Thrones’ Yara Greyjoy), as the genderqueer Bobby Page of Jackie Clune’s “The Perfect Gentleman,” engages in a bit of pronoun play, the effect is mesmerizing because the quiet draws us in; the series trusts that the secret codes of mutual recognition are compelling in their own right. After all, queers found each other, in barracks and back rooms and moonlit parks, in nightclubs and chat rooms and dark corners at college parties, long before “coming out,” in its modern iteration, became a rite of passage. Queers understands, with reference to the Wolfenden Report, the Sexual Offences Act and Margaret Thatcher’s murderous mishandling of the AIDS crisis, that so much of what it means to be queer is shaping one’s life, oneself, to fit into the crevices straight people leave open, and that this is why coming out, that act of self-revelation, remains radical even now. Whatever its form—the stolen glance, the illicit embrace, the shy conversation, the bold proclamation—it is a request, a demand, to be seen by another, even when we’re forced to shrink at the behest of the state.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-