Adam Sternbergh Delivers Witness Protection with a Speculative Twist in The Blinds

As the creator of a dystopian Manhattan in the Spademan novels Shovel Ready and Near Enemy, Adam Sternbergh arrives well-equipped to construct a bleak Texas town in his new book, The Blinds. Caesura (nicknamed “The Blinds”) is a dead-end outpost conceived out of experimental optimism. Each resident, placed there as part of a privately funded relocation program, is essentially entering WITSEC with a speculative twist. Before being sent to the Blinds, each person agrees to have his or her memory at least partially erased to remove any reminder of crimes committed or witnessed.

Each Caesuran has been granted “a new you, a new life, a new start” based on the town’s credo: “If you want to keep a secret, you must also hide it from yourself.” Caesura founder Dr. Holliday makes a case for the merits of the Caesura approach over the witness protection program, saying, “In WITSEC, you get a new identity and a new home, but you’re still fundamentally you—with all your criminal history, proclivities, predilections, and expertise—and you’re planted in an existing community full of unsuspecting innocent people.”

In keeping with this clean-slate reset, each resident is required to choose a new name—one each from a list of vice presidents and movie stars. Thus these voluntary amnesiacs find themselves beginning new lives with names like Hubert Humphrey Gable, Bette Burr, Marilyn Roosevelt, Spiro Mitchum and Gerald Dean. They live in uneasy ignorance of whether their former selves (or their current neighbors) were mass murderers, contract killers, mobsters, rapists or the “innocents” who sent real offenders to prison.

In keeping with this clean-slate reset, each resident is required to choose a new name—one each from a list of vice presidents and movie stars. Thus these voluntary amnesiacs find themselves beginning new lives with names like Hubert Humphrey Gable, Bette Burr, Marilyn Roosevelt, Spiro Mitchum and Gerald Dean. They live in uneasy ignorance of whether their former selves (or their current neighbors) were mass murderers, contract killers, mobsters, rapists or the “innocents” who sent real offenders to prison.

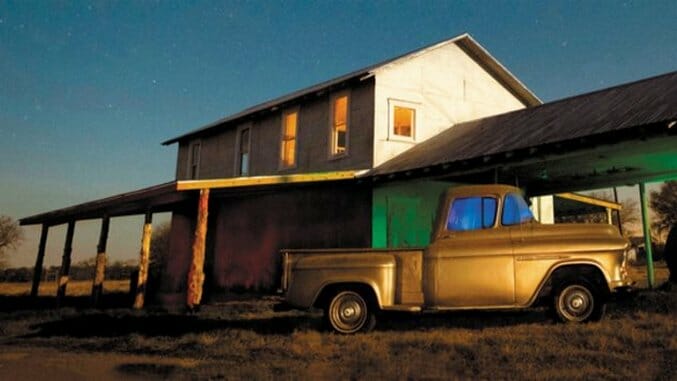

Although many of the Blinds’ residents hail from the ranks of violent criminals, Caesura is no prison. As Calvin Cooper, the town’s sheriff of eight years and the book’s conflicted central character, quips in his canned speech to new arrivals, “Despite the perimeter fence and the various rules, your residency here is not a punishment. You are not in jail. You are not in hell. You are in Texas.”

He goes on to explain that residents are welcome to the middling pleasures of the town’s bar, library, gym and poorly stocked commissary, and they are free to leave at any time. But he also notes that they are forbidden any communication with the outside world, lest the outside world locate them. He warns those who have chosen to leave have not survived long, presumably killed by former associates.

As The Blinds begins, two deaths-by-gunshot—one officially deemed a suicide—have recently roiled the town’s placid surface. Sheriff Cooper is determined to keep the uneasy peace, while his new deputy, a young woman who has chosen the Blinds name Sidney Dawes, resolves to solve the crimes that have cracked Caesura’s tenuously calm surface.

In The Blinds’ hard-boiled narrative, Sternbergh delivers cutting humor and devastating violence that shows little regard for readers of delicate sensitivities. He fashions intriguing characters out of amnesiacs who are afraid to remember past misdeeds. There’s real pathos in Cooper’s clumsy efforts to protect his charges, regardless of their possible past identities—or his own.

What’s more, The Blinds questions the connection of character and fate. It plumbs the inescapability of pasts too horrifying to face with a resonance reminiscent of Thomas Hardy’s The Mayor of Casterbridge, but Sternbergh conveys a violent, bracing immediacy that Hardy never achieves. The Blinds ponders the question of whether a well-intentioned present can be separated from an unforgivable past. Is a person still the sum of their past misdeeds if they can’t remember them? Could a crime boss-turned-informant like Jimmy Frattiano or Whitey Bulger, or a mass murderer seemingly beyond redemption, a Richard Speck or a David Berkowitz or an Ed Gein, simply become another mild-mannered neighbor with a wiped memory and a fresh start?

The Blinds doesn’t explicitly ask these questions, nor does it offer a single answer. But it impels the reader to ask them, which is exactly what enduring novels do.

Steve Nathans-Kelly is a writer and editor based in Ithaca, New York.