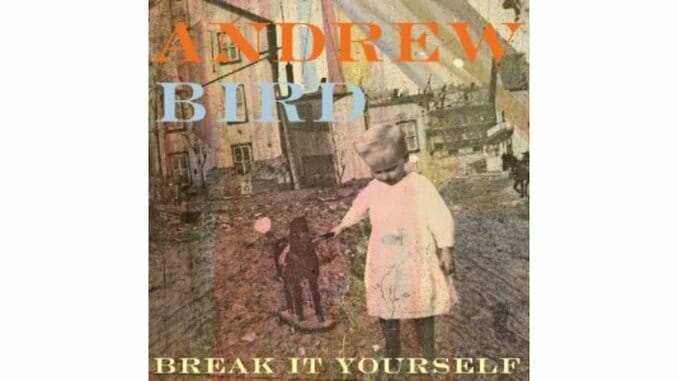

Andrew Bird: Break It Yourself

Last year, Andrew Bird contributed a cover of the Kermit the Frog classic “Bein’ Green” to a Muppets tribute album. Elsewhere, he partnered with sculptor and instrument maker Ian Schneller on a performance and installation involving speakers made from recycled newspapers and dryer lint. He follows the same definition of “quirky” that people use for Wes Anderson movies — his interests are idiosyncratic, to be sure, but somehow the definition feels too overreaching, like using Instagram and “hipster” in the same breath. (Bird, this week, actually used Instagram to promote the album, so, there you go.)

Bird’s seventh solo album, Break It Yourself, will likely set itself up for those dreaded descriptors, from the titles onward. There are references to Greek mythology, to horrible international tragedies. There’s a fake palindrome (how meta!). There is, per usual, quite a fair amount of whistling. It is, however, a bit more reserved than the earlier Birds (groan). Long gone are the rapturous flourishes of “Fake Palindromes” and even further the weird but awesome swing revival phase in which he participated as a Squirrel Nut Zipper. What we’re left with is a guy, with a violin, an embouchure of pure steel, and a set of sweet, gentle (though occasionally a bit too much so) jams that will come to you with good intentions. Break It Yourself greets its listener like a friend-turned-lover making the first move: sitting on opposite ends of the couch, inching closer and putting its arm around you and by the end, you’re curled up together, sleepy but overall content.

From the outset, it seems that “sleepy” will be the decisive adjective of this album. “Desperation Breeds…” a song in which Bird sings about the plight of our ecosystem and rapidly declining bee populations, even begins on a downbeat. The lack of urgency about such an important issue to human survival seems a bit odd, but as with quite a bit of this album, Bird’s songs start to peek out of their shells a third, halfway through, and come around the corner with vocal whinnies or stunning vibratos or gorgeous swells that make it worth sticking around.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-