Autumn Classics: The Blair Witch Project

20 years ago, indie filmmakers gave birth to found-footage horror.

As the nights get colder and the local café starts pushing pumpkin-flavored everything, many a movie lover feels the urge to stay indoors and revisit the dark, unsettling, or tragic films that evoke the spirit of the season. This October, Ken Lowe is revisiting four of these Autumn Classics. You can read up on his previous picks here.

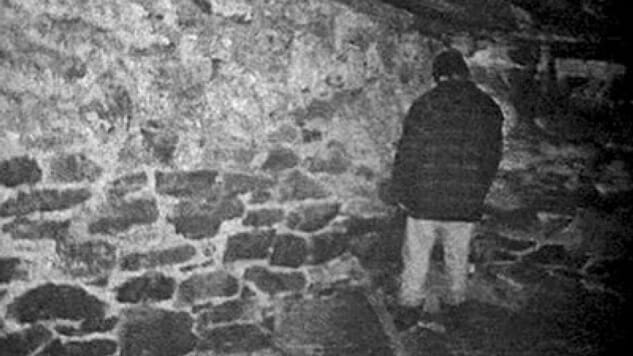

Paste’s own Jim Vorel rightly named The Sixth Sense as 1999’s best horror film. But while M. Night Shyamalan’s story of a haunted young boy (and the spoiler who helps him) met with critical acclaim and launched that director’s career, there was one other horror sensation that year that arguably had even further cultural reach. It birthed the found-footage horror subgenre, it went “viral” in a time before things went viral, and its DNA is still present in the phenomenon that is the creepypasta community. And by dint of its gloomy backwoods setting and focus on characters menaced by dark, cold and their own paranoia in the face of the unknowable, it’s an autumn movie through and through.

Three college-age kids vanished in the woods a few years ago, the movie’s dire opening chyron informs us, and we are about to watch the footage that was recovered a year later. The movie follows ringleader Heather Donahue and reluctant cameramen Michael Williams and Joshua Leonard (all played by actors with the same names) as they attempt to gather footage for a documentary about the Blair Witch, a local legend in a small Maryland town. They first interview several local townspeople whose stories never quite line up or even seem particularly trustworthy, and then they venture into the nearby woods to find and film sites featured in the town’s grisly history.

It becomes clear fairly early on that Heather doesn’t really know what she’s doing or where she’s going, a situation that eventually leads to a breakdown in unit cohesion and the trio becoming hopelessly lost in the woods with dwindling supplies and odd and scary noises in the night that follow them around. As they fail to find their way back to civilization for days, Heather steadfastly refuses to quit filming and we get a first person view of the crew’s starvation, sleep deprivation and emotional collapse.

It isn’t until relatively late in the film that things start going bump in the night, and it begins to seem inevitable that they’ll fall into the clutches of the one spooky story that’s actually true.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-