Five Things I Learned About AB-InBev While Reading Barrel-Aged Stout and Selling Out

Photos via The High End

Here’s something that I know is true of myself, and I assume is probably true of a lot of other beer writers: We don’t necessarily read a lot of physical books about beer these days.

Oh, perhaps we did once upon a time. I certainly read beer books voraciously in the late 2000’s, devouring information (as it existed at the time) about beer styles, beer history, homebrewing (thanks, Charlie Papazian!), beer science and the occasional forays into beer politics and economics. But once you become really invested in a subject like beer, or embedded in some niche within the brewery landscape itself, new beer books tend to lose their allure—especially books in the “here’s what’s going on in beer right now” vein. Why? Because for one, they’re likely to be out of date by the time they even reach publication. The more the pace of change within craft beer accelerates, the shorter the shelf life is of those books.

It’s certainly true of almost everything written in print about beer styles. Just look at something like former Stone brewmaster Mitch Steele’s important IPA: Brewing Techniques, Recipes and the Evolution of India Pale Ale, first published in 2012. When it hit the shelves, beer fans gobbled it up as “the essential book on IPA.” But now, a few years later, IPA is so vastly different that you’d hardly recognize it from the template Steele was working from at the time. That’s just the reality: Any end-all, be-all book on the style published today would have to dive deeply into new IPA substyles—especially hazy IPA—and that book would likely end up obsolete a few years from now when we’re all drinking VIRTUAL IPA’S made with DIGITAL HOP PROCESSING, etc.

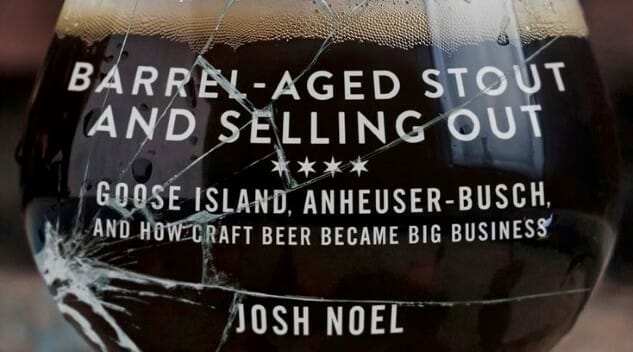

Still. There are the rare exceptions when I’m really looking forward to reading a beer book, and that was the case with Josh Noel’s Barrel-Aged Stout and Selling Out, which officially hits bookstores on June 1, but is already available online. This was for a few reasons:

— I’m from the Chicago suburbs, and Goose Island was one of the first “craft breweries” I ever became aware of while coming of age.

— Their 2011 sale to Anheuser-Busch InBev kicked off the “acquisition era” of craft beer that has continued to this day. When it happened, nobody quite knew how to react, or what it would mean for the next era of craft beer proliferation.

— Given that I’m a longtime Chicago Tribune subscriber (and former newspaper reporter myself), I’ve long read Josh Noel’s beer reporting on my hometown. Full disclosure: We’ve chatted occasionally via Twitter and are friendly, in a colleaguial sense.

I also found myself appreciating, as I tucked into the book, that it functions both as a history and as an illuminating look into how the world’s largest beer conglomerate tends to do business. There’s a wealth of information here present about the acquisitions of not just Goose Island, but all the other breweries since acquired by Anheuser-Busch InBev—which now includes Blue Point, 10 Barrel, Four Peaks, Breckenridge, Devil’s Backbone, Elysian, Golden Road, Karbach and Wicked Weed, although you of course won’t find reference to ownership on any of their packaging.

In the course of reading, I was entertained and informed in equal measure. There was a lot about the story of Goose Island I was already aware of, simply by virtue of having been paying attention when it happened. Who could forget, for instance, the incident when Goose Island brewmaster Greg Hall ended up in hot water just days after the sale was announced when he started peeing in beer glasses at Chicago beer bar Bangers & Lace? At the time, it certainly felt like a pretty clear admission that not everyone was pleased with the transaction.

However, there’s also plenty in Barrel-Aged Stout and Selling Out that was new to me, and many of the most interesting tidbits are related to the operations of AB InBev and how they handled the acquisition. And so, allow me to list: Five things I learned about AB InBev while reading Barrel-Aged Stout and Selling Out.

1. AB InBev Put a Guy in Control of Goose Island Who Knew Nothing About Craft Beer

When Goose Island founder John Hall stepped down at the end of 2012, despite originally intending to stay for three to five years after the 2011 sale, AB InBev appointed Andy Goeler to run Goose Island in its senior executive position. He was an AB lifer who was named the director of marketing for Bud Light in 1995, during the time when it surpassed Bud Heavy to become the nation’s #1 beer. He believed intensely in the company, was one of its most loyal soldiers, and had a proven track record for marketing. He also apparently didn’t know anything about craft beer, in even an academic sense, when he was put in charge of Goose Island. Writes Noel:

Goeler’s talent was as a Big Beer guy. Suddenly he was a Small Beer guy—tasked with turning it into Big Beer. The fit was as odd as it might seem. When he professed a fondness for the seasonal Mild Winter, a Goose Island employee mentioned that the beer featured rye in the grain bill, a fairly standard ingredient in a craft brewery.

“I didn’t know you could put rye in beer!” Goeler said.

This is a guy who had worked in the beer industry for decades, but his conception of what beer could be was so narrow that he’d never done the most basic reading on the topic. Now he was the final say on which beers would be produced at a brewery that had pioneered such processes as barrel-aging and wild-fermented beers in the years prior. This was, suffice to say, a bad idea. Today, Goeler is once again the vice president of Bud Light.

Andy Goeler’s crafty portrait from his time as vice president of marketing for AB InBev’s The High End, after the Goose Island post.

Andy Goeler’s crafty portrait from his time as vice president of marketing for AB InBev’s The High End, after the Goose Island post.

AB InBev had purchased Goose Island, but they didn’t understand a thing about the product coming out of the brewery they just bought. At Goose Island events, the representatives from AB InBev would show up and drink Bud Light. Few displayed any interest in learning about the thing they were trying to sell. The corporate mind revolved around massive, wholesale-centric events such as SAMCOM, the annual Wholesaler Sales & Marketing Communication Meeting. As Noel writes:

The Anheuser-Busch galaxy revolved around SAMCOM, the annual conference where wholesalers gathered under one roof to be fired up and fed marching orders for the coming year. Inside the brewery, plans needed to be discussed in May so they could be finalized in September, then rolled out at SAMCOM in November.

John Hall, meanwhile, somehow managed to be distressed by many of the things happening, despite the fact that he signed away his ability to make any of the final decisions, even before stepping down. In truth, he seemed to feel the rug pulled out from under him after the first year when they guy he “made the deal” with, Anheuser-Busch president Dave Peacock, stepped down from his post. That left Hall reporting directly to AB InBev’s Brazilian ownership. Or as the book reads:

When he agreed to sell, John figured he would be tethered to, and protected by, Peacock. It was as if John had sold his company to him—not these faceless Brazilians. But now Peacock was out as president of Anheuser-Busch, and the company hadn’t even bothered to replace him. John was left to report to Peacock’s old boss—Luiz Edmond, the head of AB InBev’s North American operation.

It seems rather naive of Hall to think that his company would somehow be “protected” from meddling by a global mega-giant, but at the same time, we should keep in mind that Goose Island was serving as a testing ground for what acquisition by AB InBev would look like. He made the deal, hoped for the best, and got something significantly less than “the best.”

2. AB InBev Gave Goose Island Zero Input on the Brand’s Initial National Rollout

When it came time for the brand’s long-awaited national rollout—really, the reason why AB InBev would ever acquire a craft brewery to begin with—Goose Island and AB InBev disagreed starkly about how it should happen.

Goose Island’s leadership (not yet replaced by the likes of Andy Goeler) argued that it should be “a slow, measured rollout—starting with full distribution through the East, then to the South, then inching West. Along the way, Anheuser-Busch distributors and their sales forces would need to be educated about the brewery, the brand and the nuances that distinguished a wheat ale from a pale ale, a Guinness from a Bourbon County Stout. As things stood, distributors didn’t understand the brand and lacked the tools to make it succeed. Pushing distribution ahead of awareness might lead to short-term boost, but it wasn’t sustainable.”

AB InBev disagreed. As Noel writes, “Goose Island never even got the courtesy of a call to learn that it was relegated to bit player for its own rollout.” He continues:

Anheuser-Busch was orchestrating the rollout behind their backs. The timing wasn’t meant to suit Goose Island; it was meant to fire up Anheuser-Busch wholesalers, who would hear details at that fall’s SAMCOM. A rollout that should have taken years would happen in months.

If you’re wondering how that rollout ended up going, the answer is “fine … at first.” In 2013, as the brand expanded nationwide, sales were obviously way, way up. In 2014, however, former Goose Island flagship Honker’s Ale actually decreased 18.6% in sales, while the brewery’s biggest beer, 312 Urban Wheat Ale, was flat. The only style that continued growing was Goose Island IPA, but even that brand’s 33% growth in 2014 was way, way below the rate that comparable craft IPAs were growing at as the IPA style caught fire.

In fact, much of what AB InBev subsequently tried to do with Goose Island failed commercially. They tried to spin-off the 312 brand into 312 pale ale, which was gone within a year. A similar series of seasonal hoppy beers likewise flopped. Frustrated brewers found that they weren’t even allowed to brew a Goose Island pilsner at the time, for the most pointless of reasons—it would have been “too similar” to Budweiser.

Two similar in appearance, and equally unsuccessful, beers introduced via Goose Island by AB InBev.

Two similar in appearance, and equally unsuccessful, beers introduced via Goose Island by AB InBev.

At the same time, AB InBev spurned the brewery’s oldest supporters as the brand went national:

Meanwhile, Chicago bar owners who had supported Goose Island for years were lucky to get even one case of Bourbon County Stout. They wondered why clueless, cookie-cutter chain stores were suddenly getting so much of the previous beer. The answer was that the clueless cookie-cutter chain stores churned through massive sales of 312 and IPA during the rest of the year. They were being rewarded by a new generation of Goose Island decision makers.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Chicago’s ascendant native brewery, Revolution. Bonus: They have a bar in left field at Sox Park!

Chicago’s ascendant native brewery, Revolution. Bonus: They have a bar in left field at Sox Park!