Ladee Hubbard Imagines a Superpower-Enhanced “Talented Tenth” in The Talented Ribkins

In his landmark 1903 essay, “The Talented Tenth,” African-American sociologist and civil rights activist W.E.B. DuBois declared that the best opportunities for racial uplift rested in the cultivation of black America’s brightest minds. “The Talented Tenth of the Negro race must be made leaders of thought and missionaries of culture among their people,” DuBois contended. “The Negro race, like all other races, is going to be saved by its exceptional men.”

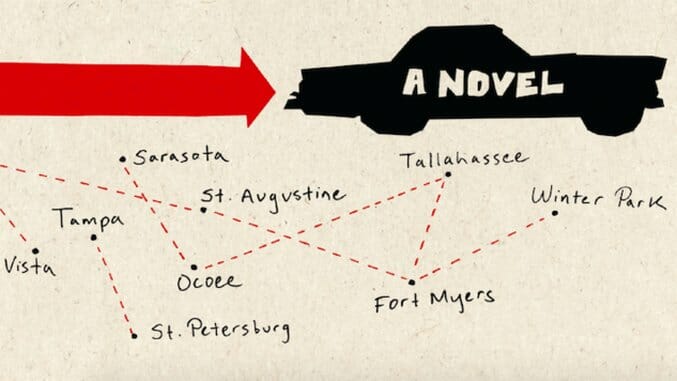

Ladee Hubbard delivers a fascinating twist on DuBois’ notion of the Talented Tenth in her debut novel, The Talented Ribkins, chronicling the travails of a family endowed with extraordinary talents. As the story begins, 72-year-old Johnny Ribkins, whose gift enables him to create detailed and precise maps of places he’s never seen, finds himself $50,000 in debt to gangsters with just a week to dig himself out of the hole. He embarks on what becomes a literal hole-digging tour of Florida, visiting all the spots where he’s buried wads of cash—mostly in the backyards of estranged relatives he hasn’t seen in years.

Now a failed and debased thief who has spent years using his mapmaking superpowers for less-than-honorable purposes, Johnny Ribkins once conceived of much greater and nobler possibilities for his talent. As a founding member of a group called the Justice Committee in the 1960s, Johnny and his fellow talented relatives and associates—including a fire-spitting cousin and a hammer-handed recruit—had dedicated their abilities to the struggle for civil rights, particularly for the protection of embattled movement leaders.

Now a failed and debased thief who has spent years using his mapmaking superpowers for less-than-honorable purposes, Johnny Ribkins once conceived of much greater and nobler possibilities for his talent. As a founding member of a group called the Justice Committee in the 1960s, Johnny and his fellow talented relatives and associates—including a fire-spitting cousin and a hammer-handed recruit—had dedicated their abilities to the struggle for civil rights, particularly for the protection of embattled movement leaders.

With Johnny’s maps as their guide, the Justice Committee “wound up spending… seven years traveling all over the south, following the progress of the civil rights movement. Staging minor interventions, doing whatever they could to help ensure the freedom of movement of people they consider heroes.” As Johnny remembers it, the group fell apart when he sequestered himself and commandeered all Committee funds to work on a map he could never finish—a four-dimensional map that would encompass not just space but time. It would help the Justice Committee become leaders rather than followers, positioning them a step ahead of their adversaries.

In its more speculative and didactic moments—as well as its ruminations on the troubled position of black genius and its chances for elevation in America—The Talented Ribkins recalls Colson Whitehead’s first novel, The Intuitionist. In particular, Johnny Ribkins’ unfinished four-dimensional map echoes the perfect elevator envisioned by Intuitionism founder James Fulton, “the one that will deliver us from the cities we suffer now, these stunted shacks.”

Also like The Intuitionist, The Talented Ribkins plays out with a peculiar combination of magic realism and bits of noir. Though replete with blundering underworld thugs, corrupt politicians, and characters deploying strange superpowers for a variety of purposes, The Talented Ribkins is most of all about intricate family dynamics, and the bonds and conflicts and tensions that endure after years of separation and divergent experiences.

Naturally, Johnny’s memories of the Justice Committee and why it collapsed are just one version of the story, according to the relatives he reconnects with during his desperate drive to clear his debt. The novel’s most beautifully realized moments concern Johnny’s evolving relationship with his newly discovered fatherless niece, Eloise, and the alternately warm and brittle scenes of reunion with his various cousins, who suspect his real motives in visiting them after years of separation.

As Johnny comes to terms with the ways he’s sold short his gift—trading in activism for thievery—he struggles with DuBois’ notion that it’s not necessity that has driven him off course, but that he has actually “mistake[n] the means of living for the object of life.” Moreover, Johnny encourages his niece to cultivate her gift rather than hiding it or passing it off as a silly trick. By hiding or debasing it, he insists, she’s denying the best part of herself—and playing into the hands of the ordinary many, who would similarly debase. “There are all kinds of people out there, got talent just like you,” he tells her. “You need to remember that because sometimes it’s hard to see it. That’s why you got to be smart enough to really look.”

Steve Nathans-Kelly is a writer and editor based in Ithaca, New York.