What PEN15 Gets Right About the Wild West of Early 2000s Chatroom Culture

Photos Courtesy of Hulu

When I was 13, my best friend used my dad’s desktop to arrange a date at Six Flags with a man she met online. Her plan was simple: she’d lie and say my family invited her to go, and instead she’d spend the day with this guy and have him drop her off at my house afterwards. I was always a careful kid, but given the advent of platforms like Myspace, LiveJournal, and AIM, I wasn’t really sure whether this was a good idea or not.

My friend, of course, got caught before it actually happened. I was relieved of my duty as her cover. Angst-ridden, she cried her way through the next few days and continued to find covert ways to talk with the guy, who had limited time because he was a community college student. She’d watch her mom type the password to their desktop, which she changed every once and a while, and sneak into the living room in the dead of night to message with him. This only went on for so long—when you’re a teen, the allure of a forbidden but tedious relationship wears off quickly. It’s relatively easy to move on from a boy no matter how you met him at this age, but the paranoia imbued in your household after a potential scare like this is lasting.

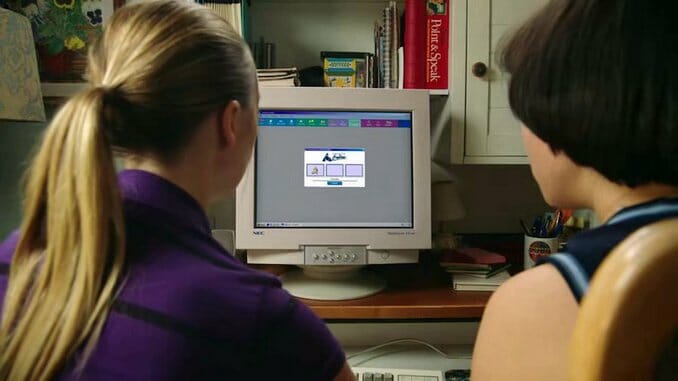

Maya Erskine and Anna Konkle’s PEN15 on Hulu has already built a niche for its uncannily accurate portrayal of growing-up-awkward-with-dial-up in the early 2000s. It’s no surprise that one of the most incisive episodes deals with the terrible twosome making AIM profiles for the first time. The episode makes liberal use of the haunting creaky door log-in noise, a sound so ingrained into the psyches of Y2K middle schoolers that it’s enough to make your neck crane towards to the nearest screen instantly.

Anna reads off a penned list of possible screen names (including “babyspice666,” which I have considered making my Twitter handle) and cheeses when the first one she tries isn’t taken. They message people from Anna’s written address book, many of which they have no business talking to like popular kids who don’t know their names. They overthink the cadence of all their broken grammar; it’s much more chill to ask “wuz up,” and their statuses are always Sugar Ray lyrics. It’s important to always seem laidback but still do the most.

PEN15 cleverly explores the exploitation of teens without actually exploiting them, and this episode is no different. The real conflict of the episode arises when Maya and Anna enter an anonymous chatroom. Skipping past rooms titled “m4m” and “local coffeeshop,” they bee line to “Hot People of Franklin County.” When you’re a preteen, you struggle to think of anyone you meet online as an adult, or maybe don’t think it matters whether they are one or not. There’s a level of distance but an edge of danger tinged with meeting strangers online. Rooms like these were chaotic and strange—bots would spam lewd messages while people ask each other unprompted what size bra they wear.

Maya, being the more impulsive friend with a far more addictive personality, immediately decides to send a photo of herself once someone privately messages her asking to prove she’s a “hot girl.” She lies and says she’s 26, but any person online would easily be able to see through this—predators often count on kids lying. “Flymiamibro22,” the profile Maya chats with, claims to be a 30 year old gym rat. Maya forges something of a connection with him right off the jump. It’s easy when you’re an impressionable teen to see what you want to see in these faceless profiles.

Yuki, Maya’s mother, does little to monitor Maya’s online behavior. Most parents at the time were either totally unaware of this early internet frontier, or sternly rejected any freedom with communication tech. My mom was one of the latter—but in 5th grade, I discovered a Pokemon forum that I frequented for the next few months and became embroiled in drama with some of the other members. I later moved to LiveJournal and Myspace. I’d add random people and chat with them, reply to their pictures, and complain about school, my parents fighting, and being in the closet.

Being young and without a therapist, this is the closest to true counseling you’ll get. Some of these people started to date remotely, which they consistently reminded me was a secret from their parents. I knew people my age who were “dating” much older partners, like men in their early 20s. At the time, I didn’t see a problem with this. Later, when I’d enter high school, several of my female friends would be picked up from school by their college-age boyfriends. I was always suspicious, but also jealous. For that reason, I can understand Maya’s want to be desired. You can dress yourself up on the internet in a way you can’t offline, and the early 2000s were a time where a picture wasn’t as often attached to a profile, and that wasn’t seen as abnormal or a red flag.

I often fantasized about meeting a man with a good job who’d come save me from the humdrum motions of my daily life. My parents fought every day, and I never saw them so much as kiss after I turned 10 or so. Chatrooms became the only place I could freely express how I felt. In middle school, emotional kids are shunned; they aren’t chill enough, they can’t go with the flow. This free expression often transformed into grotesque stream of consciousness—the show portrays this by Maya envisioning the type of guy she expects to be behind “flymiamibro22,” a tall, bearded muscle daddy. “When I think of other girls, I wanna barf my guts out,” he says. She replies with breakneck speed, saying “I wanna eat that barf and guts up like a big bowl of lentil soup, yum yum yum!”

By the season’s end, we learn flymiamibro22 isn’t a threat at all—he’s just another kid pretending to be an adult, just like Maya. But the show’s sharp instinct on the internet as a haven for the misfits is apt, and casts Maya’s temporary obsession as relatable yet dangerous. I wouldn’t have survived school without chatting about the Yeah Yeah Yeahs online with high schoolers, which, to me, meant I was ahead of my time. Few kids would survive without idle fantasies of a better life.

PEN15 is currently streaming on Hulu.

Austin Jones is a writer with eclectic media interests. You can chat with him about horror games, electronic music, Joanna Newsom and ‘80s-‘90s anime on Twitter @belfryfire

For all the latest TV news, reviews, lists and features, follow @Paste_TV.