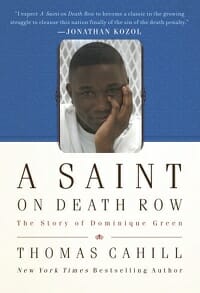

Thomas Cahill

A tale of miscarried justice and the earth-quaking power of forgiveness

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-