Wangechi Mutu Explores Afrofuturism and The New Humanism with Ndoro Na Miti

Artwork courtesy of Wangechi Mutu/Gladstone Gallery, New York

In a 1944 essay entitled Poetry and Knowledge, the Martinican poet and postcolonial theorist Aimé Césaire wrote that in the wake of slavery and colonialism, humans had been robbed of the knowledge of how to be like animals, plants, and minerals. A tree’s existence, for example, marks a form of stability as well as acceptance of the world and all kinds weather. It embraces or gives-on-and-with, while “mankind” refuses life. “And that is why mankind does not blossom at all.”

Wangechi Mutu’s new exhibition at the Gladstone Gallery echoes Césaire’s sentiment through a series of human figures and other objects made of natural materials like stone, pearls, mud, vines, and leaves. The title of the exhibit, Ndoro Na Miti (“mud and trees” in Gikuyu), is therefore literally suggestive of the materials used in their creation. But the absence of any mention of humanness is striking, as if Mutu has inverted the myth of our creation from clay with a surrealist assertion that we are indeed just organic stuff.

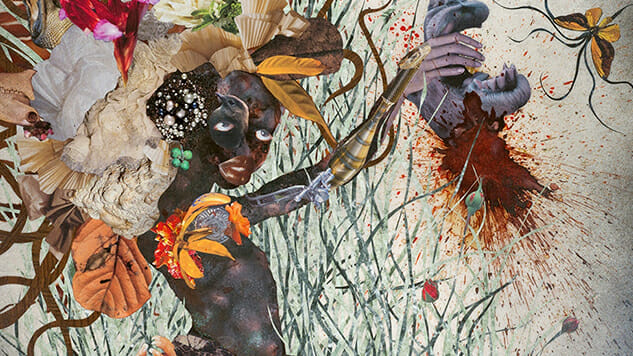

Mutu’s work has long engaged the dynamics of human creation. Many of her well known collages illustrate how the technologies of racism, nationalism, and sexism produce fully hybridized human subjects — focusing on Black women — that refuse and exceed stale racial taxonomies, even as they register the ongoing violences of confinement and assault. Previous shows of her work at the Brooklyn Museum, the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, and the Art Gallery of Ontario reveal Mutu’s sustained interest in the aesthetics of afrofuturism, speculative fiction, and mythology as modes of imparting knowledge about human experience in relation to our social and natural ecologies.

Ndoro Na Miti continues that project by focusing on the interface between human experience and the natural world, and extends the artist’s previous collage and sculptural work with the human form by substituting vibrant colors and patterns with materials and earth tones befitting the exhibit’s title. At the center of the exhibition is a bronze sculpture of an nguva, a mermaid-like figure from East African folklore that blends human characteristics with those of the dugong, a marine mammal closely related to the manatee. The reclining figure in monochromatic black inhabits its body with such ease and self-confidence that it appears to be as comfortable on land as under the sea. Yet it also introduces a recurring theme of the exhibit: what are we to make of the fact that the figure faces away from the entrance and looks askance, her expression at once indifferent and mournful?

We sense this tension between the terrible and the ordinary in five other human figures with distinctively plant- and rock-like features. It is unclear, for instance, whether “Tree Woman” is trapped in a tangle of vines or wearing them as a costume of armor. The latter is suggested by the artist’s longtime interest in “warrior women” but I read in her pose an embrace of a shared existence with plant life that is neither voluntary nor resisted. This is not surrender, but neither is it war or struggle. Likewise, in the eroded or perhaps emergent face of “Black Pearl” — a bust of coral, bone, and stone — we might perceive the face of a human metamorphosed in the moment of their last breath. Or letting off a sigh of relief. It is, in any case, far from a look of anguish.

In addition to these human figures, the exhibit features some fourteen spherical objects that evoke fantastical planets, but are listed in the catalogue as viruses. Though visually interesting in themselves, when grouped together in small phalanxes they strike an aggressive posture. Two of the orbs sit atop towers of lint, where they oversee a field of objects otherwise situated low to the ground.  By magnifying the power of these viruses, Mutu challenges one of the most important of all European humanist myths: the myth of self-sovereignty. The myth, in other words, of “mankind’s” distinctiveness from nature and its wished-for ability to dictate the terms of its engagement with the natural world. And then, of course, the viruses evoke the history of disease weaponized in the name of colonial genocides. The desire to be distinct from the natural world and the desire to weaponize it go hand in hand. Which makes another of the exhibit’s human figures, “The Giver,” all the more poignant. With head turned aside and hand outstretched, she represents a seemingly impossible ethics of simultaneous giving and receiving.

By magnifying the power of these viruses, Mutu challenges one of the most important of all European humanist myths: the myth of self-sovereignty. The myth, in other words, of “mankind’s” distinctiveness from nature and its wished-for ability to dictate the terms of its engagement with the natural world. And then, of course, the viruses evoke the history of disease weaponized in the name of colonial genocides. The desire to be distinct from the natural world and the desire to weaponize it go hand in hand. Which makes another of the exhibit’s human figures, “The Giver,” all the more poignant. With head turned aside and hand outstretched, she represents a seemingly impossible ethics of simultaneous giving and receiving.

As we face what many consider to be the planet’s sixth mass extinction event — defined as the rapid demise of a majority of the earth’s biodiversity — the urgency to respond leaves many resorting to the same strategies and technologies that have led to the crisis in the first place. No doubt those who propose that we continue obdurately to drill for oil; those who wish to colonize other planets; those who control their appetites; and those who preach self-denial sanctimoniously are different-minded in their approaches toward the consequences of climate change. But they share a common solution-oriented logic whose basic assumption is that humans must be the ones to save the world. What if humans can do nothing but destroy it? More precisely, what if mankind can do nothing but destroy it? Of course, there are other ways of being human than to be “mankind.”

Ndoro Na Miti suggests that to accept the world is sometimes to consent to violations that cannot be refused. It is a risky proposition, this idea of consenting to such transgressions (and perhaps one that our language of legal personhood is not able to describe). But we must remember that the opposite propels us toward a futile and maddening choice against mutually shared life, and that this is a choice whose logic has, over the course of recent history, authorized plans to rid the world of life itself. Ndoro Na Miti asks us to reimagine our world as if it weren’t made in the self-possessed image of “mankind.” And that weathering the storm has always been a mode of survival.

Wangechi Mutu: Ndoro Na Miti is on view until March 25, 2017 at the 21st Street location of the Gladstone Gallery, 530 West 21st Street, New York, NY.