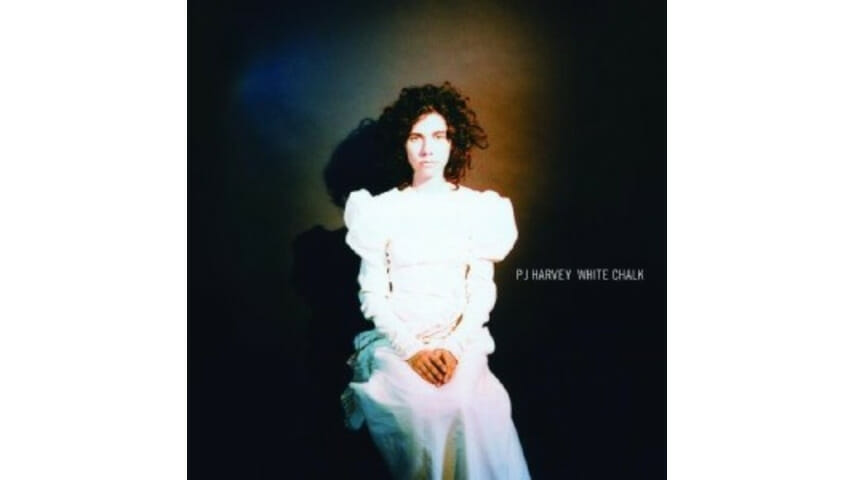

PJ Harvey: White Chalk

To Bring You My Aura

Ghost-dancing through subliminal time

You can imagine the scene at record-label headquarters as the new PJ Harvey album, White Chalk, is discussed by the execs.

“What we’ve got here is a grower!” “You mean, no hits?” “Exactly.” “Well, she’s an alternative artist. She’s not expected to have hits in the conventional sense. Just something that sticks out and says ‘I’m different.’”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-