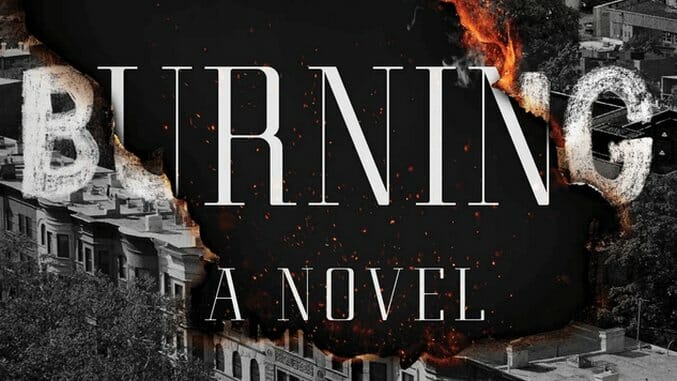

A Child’s Murder by Police Ignites Brian Platzer’s Bed-Stuy Is Burning

Brian Platzer’s new novel, Bed-Stuy Is Burning, unfolds with a “ripped from the headlines” feel. This is partly because its subject matter is so topical, exploring urban neighborhoods’ racial and class tensions following the murders of young black men by white policemen. The novel delivers a plausible blow-by-blow of how stop-and-frisk policing in urban areas gives way to police violence—and how angry tweetstorms spill over into physical confrontations.

The spark that lights the fire in Bed-Stuy Is Burning—a black child’s murder by police in a neighborhood park—closely parallels tragedies that occurred with infuriating regularity as Platzer was writing the book…and will occur in the months following its publication. In that sense, the novel is contemporary in its concerns.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Perhaps the most striking divergence between Bed-Stuy Is Burning and Do the Right Thing is the vast class difference at its core. Do the Right Thing dramatizes racial tensions between white store-owners and black residents in Bed-Stuy in the 1980s. Much like the Roxbury and Southie neighborhoods that squared off in the Boston busing battles of the 1970s, the Brooklyn neighborhoods of Bed-Stuy and Bensonhurst that clash in Do the Right Thing are essentially racially segregated working-class communities situated in uncomfortable proximity to one another. Bed-Stuy Is Burning, by contrast, captures a formerly all-black neighborhood in uneasy transition, centering on two white yuppies and their infant son, who have recently moved in after purchasing a historic Bed-Stuy brownstone for $1.3 million.

Perhaps the most striking divergence between Bed-Stuy Is Burning and Do the Right Thing is the vast class difference at its core. Do the Right Thing dramatizes racial tensions between white store-owners and black residents in Bed-Stuy in the 1980s. Much like the Roxbury and Southie neighborhoods that squared off in the Boston busing battles of the 1970s, the Brooklyn neighborhoods of Bed-Stuy and Bensonhurst that clash in Do the Right Thing are essentially racially segregated working-class communities situated in uncomfortable proximity to one another. Bed-Stuy Is Burning, by contrast, captures a formerly all-black neighborhood in uneasy transition, centering on two white yuppies and their infant son, who have recently moved in after purchasing a historic Bed-Stuy brownstone for $1.3 million.