Paste Alum Charles McNair’s The Epicureans Is a Feast of a Novel about Billionaire Cannibals

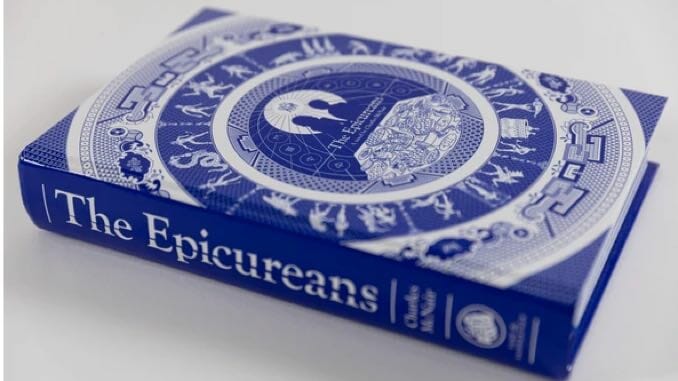

The Epicureans is the third novel by former Paste Books editor, Charles McNair. It’s also the second release from Tune & Fairweather, the Irish publishing house founded by former Paste deputy editor Jason Killingsworth, after launching with a coffee table book on the game Dark Souls called You Died. So my love for the book and its gorgeous illustrated, hardcover treatment is clearly tied up in my friendship with those who made it. But I was a fan of McNair’s first Pulitzer-nominated novel Land o’ Goshen long before I ever met him or he started working for Paste. And I’m confident I would have no less love for this book if our paths had never crossed. The Epicureans is a Southern gothic tale that would have had Flannery O’Connor on the edge of her reading chair. The most primal of horrors lurk at the back of McNair’s latest novel, but he has imbued his tale with so much humanity and grace that neither the darkness of billionaire cannibals nor the everyday monsters we all must face can keep that Alabama sunshine from bursting through.

I spoke with McNair by phone from his home in Bogota, Colombia, last week.

Paste: I love Tom Junod’s description of this book. He says, “It’s a Grimm fairytale for the age of income inequality.” Where did the idea come from to write a book about a group of evil billionaires?

Charles McNair: You know, I can put it to the exact moment that this idea was born. I was riding on Peachtree Street with my child. And it was a joy ride on a Friday night, which we liked to do just to see the sights. And while we rode, I said, “What if there was this club that had infinite money and infinite power to do whatever it wanted to be the ultimate foodie group—and what they chose to do with their passion was to eat?” If you draw the line as far out as it goes, the ultimate consumer foodie trend could be eating other people. And so that was the moment, and we reflected on that in the car, and that sort of took shape. Writers have a lot of ideas—the bad ideas, thank goodness don’t germinate, and they’re the ones you just forget. But this thing took hold, and just kept in there—there was something to it. So I wrote that first chapter to the book, which really has not changed since the very first strike. So you’ve got the idea of this club and the kid—who are the kids, and what’s the backstory of who is vulnerable? And who was behind it all? Josh, it was my wish for a long time, you know—I’ve seen the villains, I’ve seen the the Hannibal Lecters, and I’ve seen the real villains, the Mansons and all the bad guys through the years, and I can’t imagine who would be the absolute most evil of all the evil characters—what is the ultimate? And I tried to create that character in this book and give the furthest extreme of what human malevolence can do, and that’s what Mr. Wood represents.

Paste: Yeah, Mr. Wood definitely comes across as not just the most evil, but the most powerful and evil, with everything that is at his disposal—not just in money and resources, but the evil genius behind it all. Did you ever have a boss like a Mr. Wood? Was there ever some person in your life where you thought, “Oh, this guy, if he had the money and power to do anything, would just be dirty.” Where did Mr. Wood come from?

McNair: I never had a boss that bad. And I did have some tyrannical personalities to work for in my life, but nobody like that. Thank goodness. I will say, though, that Mr. Wood is wholly a fictional creation. He came from this imagined place: “What would he look like? Some things you’ve seen—the white hat and the fringed jacket. I didn’t ever know anybody that wore those, but they exist, and I can imagine a character who chooses that as his look. And why is that the Ultimate Evil? I don’t really know. It just seems like the visual details that would make him weird and scary and ominous. A white hat is what the hero usually wears. A fringed jacket? That’s Daniel Boone’s jacket, a great American hero, or so they say. But when you put them on this fella, and wrap something so evil in that, it just seemed fresh and original, something that would be memorable to a reader. And that’s what I wanted him to be—I wanted to write the baddest bad man that has ever been in fiction. Don’t fault me for ambition. Whether I succeed, that’s a whole different matter. But I gave it a shot.

Paste: I think you hit the mark. The villains of this story are billionaires who are actual cannibals. It’s hard not to see that as a metaphor for the ultra-rich feasting on the rest of us.

McNair: Well, that’s for a reader to decide. But I surely bear some sense, like most decent people do, that that is a metaphor. Just because I’m not good at making money doesn’t mean that somebody who really is good at, that that’s their talent. I can write. I can’t make $2 billion or $400 billion, like some people are able to do. That’s their talent. But just because you’re good at that doesn’t mean that you should have more than you really need. What’s the difference in $2 billion and $200 billion? When you get right down to it, what can $2 billion not buy? Why do you need $200 billion or $1 trillion?

Paste: In The Epicureans, you have scenes with these uber-rich, planning and executing their nefarious deeds. But then there’s this very human story of a family in rural Alabama. I enjoy the sort of dichotomy of those scenes, and I enjoy reading about your hero here, Elmore Rogers, a dad just trying to get by and make things work out for his family and take care of his kids. Can you tell me a little bit about writing about that world of Alabama you left behind so many years ago, to Italy back in your younger days, to Atlanta for a very long time, and now to Colombia? How have all of all your travels given you that perspective on the Alabama of your youth?

McNair: You know, it’s what I am. I may be far away from it physically, but that is what shaped my values and shaped my perceptions of what worthiness is. What courage is to my hero, who is named for the two men who worked for my dad on the construction crew in Alabama. The foreman was a white guy named Jean Elmore. He was a country boy who didn’t go past the third or fourth grade school, but he could read a framing square and he could put up a house, which was more than I could do. I spent my years from age 10 into my early 20s, working in the summers working with Jean. The other man on the crew was Willy Rogers, and Willy was a black man who never went to school. I don’t think he had one minute of education in his life, and daddy hired him at age 18. And he became daddy’s man. He helped build every house, every construction ever put up. He worked on the weekends doing farm work and helping my dad on some country properties, on keeping those properties maintained. That’s what his life was. He was super human in strength and endurance. We used to have races to dig ditches on the foundations in the houses we were working on. There I was—18, 19, 20—I was a young buck and thought I was hot stuff, and he would leave me in the dust. He was like John Henry. It taught me something about race, to work beside him, and understand no matter how good I was, somebody else was always better. And it could be the humblest guy, it could be the foreman in his pickup truck. I was taught the lesson that I wasn’t better than anybody in the world. And I don’t believe anybody’s better than me. But I certainly have no reason to thump my chest and to pretend that I’m better than other people, because I worked by people who were better than me at what they did. And I’ll never be that good, ever. So those lessons, Josh, learning those things and seeing those things with our own eyes, they shaped my worldview. That’s where I learned those primary lessons that showed me how the world works.

Paste: I also love how in your writing—really in all of your novels—the natural world of Alabama—the whip-poor-wills and cottonmouths— come through. You just capture that sense of place. I know Alabama clearly means a lot to you—you’ve got a tattoo of a banjo on your knee. How do you bring those memories back onto the page?

McNair: I’ll say for starters that I believe the greatest gift that I ever had in my life was 100 acres of woods behind the house in Dothan, Alabama, where I spent age six to age eighteen—all of my educational years. First grade to graduating from high school, those woods were back there. And there was not a summer day ever, no matter what else happened or what else was going on in, that I wasn’t back in those woods. I tell people I was a large, red woodland animal. And except for Sunday mornings when we went to church—and this sounds so hokey—but I never had on a pair of shoes in the summers, at least until junior in high school. So the things you see in the woods and the things you learn about nature and the miracles that you see, you could spend your life looking—you know this, you’re a birder now—you can spend your life in one acre of woodland from now on, and you would never, ever be done telling the stories that you see there and observing the birdlife and the cycles and the births and the endings. It is the richest place in the world. And so it is with me and and those years in that 100 acres behind the house on Parish Street, which was a dirt street. And when my dad first built the house there, there were only about five houses on the whole street. So it was natural. It was so unlike the world I live in in Bogota today. We fenced in some animals; we raised cows; we had chickens. I fed them every morning. I nursed a cow with a bucket in which we made a milk mix. I wasn’t a country boy, but I was a rural boy. And there were all the different segments. There were tall pine areas. There were tangly, brambly thorn areas. There was a field where the bobwhites lived. There was a creek that ran through it. Oh my god, endless hours were spent just building dams and playing war and doing any and everything that a kid can get the neighborhood kids to do—picking blackberries, catching tadpoles. It’s a world that—Josh, does it exist anymore? Can kids do that anymore without fear of being kidnapped or being poisoned by the water back there or having somebody with a bullhorn warn them off the property? I’m not sure I wasn’t in on the very last natural America, at least in a certain kind of setting. And those are the things I write about that are the most memorable to me. I have the most facility bringing those memories back for some reason. And don’t think I don’t embroider the natural world. You know, I can make up a mythical plant or mythical animal better than the next guy. My books have put in whompas cats, which you know—are there really such things? I don’t know. You decide. I’m a fiction writer; I’ll make some things up sometimes. But I do know the world, and it’s the seedbed for my imagination.

Paste: Well, speaking of the fantastical, how much fun was it researching all the exotic meals for the Epicureans in this book?

McNair: You know, let me tell you something. The beginning chapter was sort of the entree to that kind of food writing. I finally got up to that chapter about Lake Garda, where the Epicureans’ little task force goes to do an early review of the next chef, and every single thing in that meal, except the last thing, Josh, is totally fabricated. Totally, totally made up. As far as I know, there has never been a menu that had those things. Except the last thing. That bird, the ortolon [a bunting once used in French cuisine until it was outlawed in 1999 after populations declined]. I read about that in an Esquire article written by Michael Paterniti a long time ago, and it made such an impression on me that when I decided to add the ultimate touch to the meal, that had to be the final course of a meal that this bunch of exclusive billionaires could buy for themselves. But everything else—totally made up. Fish with licorice drops? Never done, as far as I know. I just made it all up.

Paste: I love the idea of these fantastical menus of these billionaires coming up with their delicacies that haven’t been tried by mere mortals before. It’s a wonderful display.

McNair: What is it, Nashville hot chicken? How about hot hummingbird? Nashville hot Hummingbird skin. I cannot explain it, it just came to me. Where’s the channel that brings all that stuff? What have you lived in your life and thought about and done that makes that idea happen at that exact moment?

Paste: I think that speaks to a life well lived and surrounding yourself with interesting people and interesting adventures, and just triggering all of that into what you do and in your work.

McNair: I think that’s right, which is a very good argument for doing lots of things and trying lots of things. I’m in that camp.

Paste: With this book, you’ve done that as well. This book has had two very different lives—one as a serialized novel, published in The Bitter Southerner, something very unusual these days. And now, as a beautiful publication, hard bound by our friend, Jason Killingsworth and his company Tune & Fairweather. Can you talk a little bit about the the way that the publishing world has changed since your first novel Land o’ Goshen in 1994, and bringing The Epicureans to life?

McNair: I can, and I will tell you that those changes are directly accountable for this book and its evolution. My first novel, Land o’ Goshen, was traditionally agented, edited, published and marketed, and it did okay. By the time, 20 years later, I had finished my second novel Pickett’s Charge—in those 20 years I became a dad. My focus was not only just on this selfish hobby I had of writing fiction, but on other things in the world, like trying to make other people secure. By the time that came around, I went to a traditional publisher and sent the manuscript on the eve of the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg—this book had a Civil War theme. That was the perfect marketing anchor, I thought for it. The book went to a major publisher and was on the desk of a great editor, and my agent died. And the book sat on that desk for a year. And I kept imploring people there to let me know something—yes, no, maybe, whatever. At some point, I gave up. I said, “Okay, well, I’m never gonna have another 150th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg, and I’m gonna use this one. And I took the book back and took it to a small press in Alabama, Livingston Press, which moved as fast as it could. It didn’t quite make the anniversary. But it got the book out during the Civil War 150-year window. And I’m very proud of that book. I think it is so relevant right now to this national divide and issues of the old Confederacy. But time moved on. That book was published in 2013, and I had about 20-something chapters underway of The Epicureans at some point, and I approached Chuck Reece of The Bitter Southerner. Unhappy about the idea of going back and finding an agent—I hear every nightmare story you can imagine about people trying to land an agent these days. And I just wasn’t willing to go spend all that time doing that. I might do that again. But for this one, I said, “Why not experiment? I’m going to publish this in a serial, and maybe an agent or a publisher will come to me, instead of me having to go through endless pleadings and submissions to maybe come to nothing in the end.” So I started publishing the book, and the first 27, 28 chapters appeared. And guess what? I’m over a barrel. I have 13 chapters still to write. There’s one week of deadline on each one. And, Josh, I don’t know what’s gonna happen at the end of the book. I wrote the last 13 chapters of The Epicureans without having a clue what the ending of the book would be. I just took a leap. And somehow, like this giant gift of divination or prophecy or whatever, I invented an ending that clicked, and satisfied me, readers, and was fitting to the beginnings of the book, which was so promising.

And so, sure enough, the book appeared in serial, and it took a little while. I had an inquiry or two from here and there. But then the big one came, which was Jason with this first book that Tune & Fairweather had done [You Died], which is like the most gobsmacking book you’ve ever seen. And he wanted to publish mine as the first book of fiction at the new house. So yes, sir, sign me up. And the model was different. It was a Kickstarter campaign. Readers, if you’re interested and want to see a good book by a good writer, this is your chance. You’re a patron of the arts. You get a collectible item for your your investment in the book. And miraculously that happened. And so every step of the journey on this book has been an experiment for me, and a different model for me. And at some point in my life, I’ll look back and I’ll say, “That was the smartest thing you ever did or that was a sidetrack.” And it’s a gorgeous, beautiful book. Maybe the old-fashioned publishing world turns out to be the right model. In the end, I don’t know. You’re just out here exploring space. But I can’t tell you how in awe I am of Jason and his creative brilliance in designing this book—and Andrew Hind, his designer. Have they created a work of art? I think you would agree just looking at it and holding it in your hand. Have you ever seen a book of fiction more beautiful than that one?

Paste: It makes me think of antiquity—old monks spending time with their illustrations. But in a modern context of fiction? No, I have not. I can only imagine what that felt like to have your words treated in such a way.

McNair: Let me add this one thing: I’ve done three books—two previous fictions and one history of Sam Massell, the mayor of Atlanta. I have never once sat down, since those books were published, and read any of them, until now. I spent last week showing some COVID-like symptoms, and, of course, the alarm bells went off around here. I got quarantined, which is about the best thing that can happen to a writer. So I’m quarantining here in the house. And I look at that book. That blue cover is like an eye magnet—you can’t not see that blue, that willow-China-pattern blue, if you’re in the room with it. And I went over and I picked up the book and lay down on the bed and started reading my own novel. And I flipped the pages. It was like a dream to read the book fresh. I haven’t looked at it in a long time. And to finish a chapter and say, “Wow, that worked.” And then another chapter and say, “That worked.” And to get all the way through to the end—I don’t want to be a spoiler but an important character is buried at the end, and my eyes filled with tears. And I got this lump in my throat and that stinging burst of tears in your eyes. And I put down, and I said, “That’s a good book.” I held it up to [my wife] Adela. I said, “This is a good book.” And it’s marvelous to me that that I did that. And that it has this respectable, respected treatment that Jason gave it. It’s an honor, and I can’t tell you how touching that is. And I’m looking at it right now. There it is. My book. I did that. And wow, what else can I say?

The Epicureans is available now in hardcover and digital editions from Tune & Fairweather.

Josh Jackson is Paste’s co-founder and editor-in-chief.