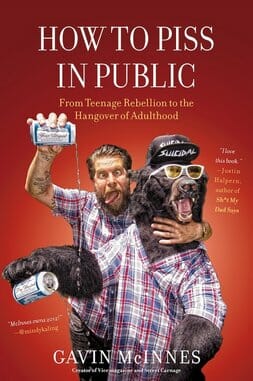

How to Piss in Public by Gavin McInnes

Of Vice and Men

In the last few years, hipster hating has become a popular sport. There is no shortage of spite published, in print and on the World Wide Web, about vintage-clothed, ironic-toned youth. As Amanda Marcotte at The XX Factor blog says, “… the term ‘hipster’ has become a signal to people that it’s safe to engage in the all-American sport of arguing that we don’t need no stinkin’ culture, and that arty-farty people are elitist scum.”

Gavin McInnes, creator of Vice magazine and the hipster movement’s alleged maker, at once owns up to being its source and leaves it in the dust in his book How to Piss in Public.

After Vice went broke in 2001, the magazine offices moved from Manhattan to the “crack-infested, glass-strewn alleyways of Williamsburg, Brooklyn,” McInnes writes. “Today it is known as the ‘hipster mecca’ but it wasn’t pretty back then. You’re welcome for the conversion, or maybe I apologize.”

Within this statement lies a whole mess of contradictions that inform not only the generation of twenty-somethings deemed hipsters (and some now moving into their thirties), but also society’s popular opinion of them. McInnes expresses the veiled shame of anyone deemed a hipster, while accepting the inherent glamour of spawning a generational movement … even though artists were moving to Williamsburg when McInnes still wore diapers.

How to Piss in Public is McInnes’ fifth book, first autobiography, and a hell of a ride. It exudes so much testosterone that I periodically felt the urge to put it down and wash my hands. To call Gavin McInnes sexist is a gross (and I mean that in every sense of the word) understatement. This book need not be picked up by the faint of heart, weak of stomach or thin of skin. I recommend a mind condom.

The reader follows a bumpy road through the author’s life. It starts with McInnes as a small-town Ontario boy who wants to be a punk star. He moves to Montreal, where the mandatory sex, drugs and rock start rolling. My fists clenched the book in female frustration as McInnes eulogized about how he had nothing to do in Montreal but “fuck lazy sluts so [he] carpet-bombed the city with [his] dick” after which “every pussy in the city looked like Dresden and [he] had every STD known to man.”

Special, yes? The above-mentioned passage fully reveals the infuriating man-child within this punk-rocker-writer-hipster-king who will engage in a literal or figurative pissing contest without being asked. But it also points to two other aspects of the writer’s reveal. First, we see hints of the bottomless pit that is Gavin McInnes’ self-deprecation. Second, he opens the raincoat on his desire to rouse reaction by grossing people out.

For the sake of context, it might be necessary to situate this example at the beginning of a chapter titled “The Time I Gave Myself an STD.” The story that follows involves the star of this real-life tale of terror and wonder masturbating after a gonorrhea treatment. He accidentally gives himself the STD again in such a way that in the name of public decency I feel no urge to repeat. Let readers discover on their own.

It would be too easy to simply characterize Gavin McInnes as a misogynist or say that he disrespects women, as that would gloss over his disrespect of respect itself. This book lies upon a foundational disregard for any form of behavioral order, in all aspects of humanity and society. Somehow, McInnes has managed to build a career out of this very attitude.

He hurled Montreal-born Vice magazine into this world in 1996 with the unique mission and desire to regale, repulse and reject. McInnes’s “DOs and DONTs” column, apparently inspired by his old Scottish grandmother’s sense of humor and love of dissing, have truly inspired a generation’s sense of humor. McInnes legitimized mean-spirited jokes by turning every street corner into a possible site of ridicule, whether you are an overweight woman with a camel toe or even a toddler in stupid pants. No one is safe and who knows, it might end up published. McInnes not only made public our horrific and hilarious superficial judgments, but also made them cool.

McInnes’ sometimes puerile, sometimes shocking and often gut-wrenching hijinks—some have been so edgy they actually prompted Jackass’ Johnny Knoxville to declare something in this world “off limits”—contributed to earning him that title he claims/refutes: “Godfather of Hipsterdom.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-