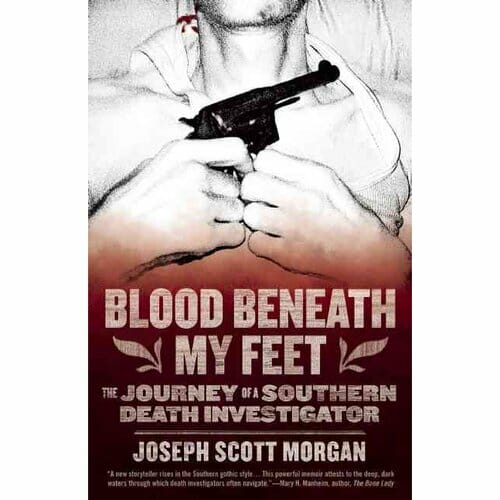

Blood Beneath My Feet: The Journey of a Southern Death Investigator by Joseph Scott Morgan

Death becomes him

Even Joseph Scott Morgan’s moniker seems like ominous, narrative foreshadowing. He was named for a homicide victim.

His beloved great uncle, Joseph, was gunned down in a Louisiana street over a painters’ union dispute, and his slayer was pardoned by Governor Earl Long. For the next 20 years, on the anniversary of the event, the family, seething with grief, sent the freed killer a black wreath with a ribbon inscribed in gold script: “We Will Not Forget.”

“From the moment I was old enough to listen, I was regaled with stories of a man I never met but for whom I bore a name,” writes Morgan. “Tales of how cruel and unjust his death was, how his killer did not receive justice but that in God’s time he would. My birthright was death.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-