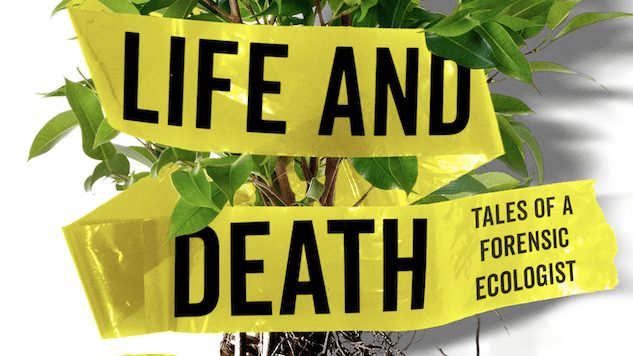

Patricia Wiltshire Utilizes Forensic Ecology to Solve Crimes in The Nature of Life and Death

Forensic ecology sounds like an almost mystical blend of detective work and science. Pollen on a jacket can wring a confession out of a rapist, the pattern of fungal growth around a corpse can provide clues to the time of murder—the possibilities are numerous. In The Nature of Life and Death: Every Body Leaves a Trace, forensic ecologist Patricia Wiltshire offers a window into her world, weaving accounts of real-life crime cases and tracing her journey from an academic researcher to a police consultant.

Upon first glance, Wiltshire’s book appears to structure chapters around crime investigations involving specific aspects of botany. In the “Poisons” chapter, she recounts the story of a shaman who was charged with manslaughter because a man had died after drinking one of his hallucinogenic brews. The shaman was exonerated, however, after Wiltshire discovered traces of cannabis, shrooms and opium poppy in the victim’s gut, suggesting that the victim had succumbed to drugs taken prior to drinking the hallucinogenic brew. But outside the particulars of each case, Wiltshire often repeats the descriptions of how she prepares the crime scene objects for analysis and what grasses, pines and nettles are found in each scene. The repeated litanies of pollen and fungi quickly become tired, and there’s no clear logic linking the crime scenes Wiltshire describes.

Wiltshire’s autobiographical accounts are similarly disorganized. Her characterizations of influential people in her life are often cursory, and people are reduced to adjectives rather than vivid imagery. A visit to the weapons storage in an Albanian police compound prompts one of the few mentions of Wiltshire’s grandfather: “I suppose he must have used the antiquated equivalent of a Kalashnikov and killed a lot of men. Poor soul—he must have had deep thoughts at times.” And similarly, the first mention of Wiltshire’s adult relationship with her mother was buried in a case description: “After two days of avoiding quarreling with her, I was glad when the police rang.”

Wiltshire’s autobiographical accounts are similarly disorganized. Her characterizations of influential people in her life are often cursory, and people are reduced to adjectives rather than vivid imagery. A visit to the weapons storage in an Albanian police compound prompts one of the few mentions of Wiltshire’s grandfather: “I suppose he must have used the antiquated equivalent of a Kalashnikov and killed a lot of men. Poor soul—he must have had deep thoughts at times.” And similarly, the first mention of Wiltshire’s adult relationship with her mother was buried in a case description: “After two days of avoiding quarreling with her, I was glad when the police rang.”

Aside from the descriptions of crime and of Wiltshire’s personal life, textbook-like segments often appear intermingled with Wiltshire’s worldview. In one instance, she declares, “The romance of death, so saturated in the art and poetry of bygone days, is so false.” She spends a paragraph explaining her rejection of the afterlife, then launches into six more paragraphs describing the process of death in a tone worthy of a lecturer. She also makes somewhat callous moralistic observations of the crime scene victims. She describes a dead prostitute’s “pathetic existence” and labels someone who died by suicide “a wounded animal.” When victims do not earn her pity, such as in the case of overdose, she pronounces judgment: “It seems sad to me that people are desperate to leave their own reality for another.”

The book’s flaws do not detract from Wiltshire’s brilliance and scientific expertise in crime-solving; her precision is evident in how she takes the reader step-by-step through her methods. But given the book’s detached treatment of not only botanical topics but also of people, the text would’ve been better suited as an academic piece or an introductory manual to forensic ecology. If readers pick up The Nature of Life and Death expecting a gripping hybrid of The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes and CSI—mixed with a dose of meditative reflections on nature à la Pilgrim at Tinker Creek—they’ll be disappointed.

Jane Huang is a neuroscience PhD student by day and freelance writer by night. She currently lives in Pittsburgh, PA.