Shelley Jackson’s Riddance Reveals We’re Closer to Ghosts—and to Death—Than We Realize

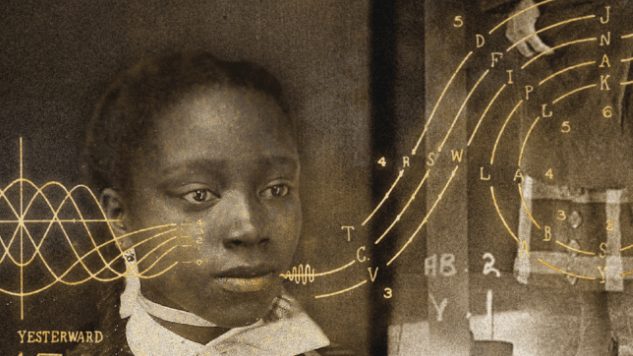

In Shelley Jackson’s Riddance, ghosts speak in the space between sounds in a child’s stutter. The mouth is the entrance and exit to the land of the dead; words and even objects from beyond the veil populate the boarding school where the children hone their abilities.

There are as many theories on the origin of specters as there are specters themselves: ephemera of massive pain; the coalesced fragments of the brain’s unused data points; emissaries of a world beyond our own; souls with business so pressing as to need a conclusion; the slip between multiple universes, us appearing as ghosts to them. All of these miss the simple—and by that terrible razor, most likely—explanation: that death, and the ghosts it creates, is the foundation of our lives.

There are as many theories on the origin of specters as there are specters themselves: ephemera of massive pain; the coalesced fragments of the brain’s unused data points; emissaries of a world beyond our own; souls with business so pressing as to need a conclusion; the slip between multiple universes, us appearing as ghosts to them. All of these miss the simple—and by that terrible razor, most likely—explanation: that death, and the ghosts it creates, is the foundation of our lives.

Colin Dickey, in his architectural and sociological story of hauntings titled Ghostland, hit on this—albeit without the fictitious pulchritude Jackson weaves in her novel. The dead are within our very walls, and not usually in the Hoffa sense. Anyone who lives in an old house knows the paths worn by previous occupants, which we in turn follow—the oil and dirt which patina walls and the spaces above door knobs.

The dead shape our perception of the living world and our actions in it, whether through wisdom from a departed loved one, tears forced by a departed friend or even reticence when approaching a tragic stretch of road. The words of old slavemasters hang the haints in Spanish moss, interlace them in the copse and swamp; the superstitions of bygone sailors populate the black sea with chimerical beats, a feat with which the ocean needs no help, all the more proving the power of the dead.

It is by the bayonets of ghosts that nations rest within their fought-for borders, that cultures continue unabated but forever wounded. Do not the words of dead authors—here, Riddance divines—reverberate through our heads as if whispered into our ears? Don’t Marx and Mussolini both sway politics from the grave?

The dead are interwoven in our genes, haunting us with diseases, reflected in the very color of our eyes. All food is of the dead, killed itself—a bolt to the brain; a plucking from the branch; a disinterment from the ground—and fed by death, so that we are fed until death collects us.

We share more similarities with Riddance’s stuttering children, who channel ghosts and even walk among them, than we share with most characters. The novel’s language, alluring and sometimes inscrutable, reflects the unknown that lies beyond, around and within us. In our contemplations—silent and distant, compared to those children—we plumb the deepest of human depths.

B. David Zarley is a freelance journalist, essayist and book/art critic based in Chicago. A former book critic for The Myrtle Beach Sun News, he is a contributing reporter to A Beautiful Perspective and has been seen in The Atlantic, Hazlitt, Jezebel, Chicago, Sports Illustrated, VICE Sports, Creators, Sports on Earth and New American Paintings, among numerous other publications. You can find him on Twitter or at his website.