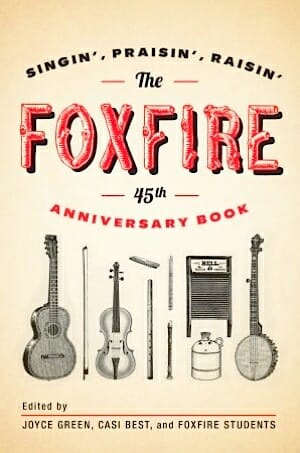

Singin’, Praisin’, Raisin’: The Foxfire 45th Anniversary Book

Edited by Joyce Green, Casi Best, and Foxfire Students

Pushing the mountains

Confronted by a claustrophobic newcomer who wanted to “reach out and push back the mountains” in Appalachia, poet Byron Herbert Reece observed: “It depends upon whether you feel you are shut in or the world shut out.”

Most of us who grew up in the Southern Highlands can see both sides from our vertiginous vantage-point: Hermits by default, we have been hemmed in—miserably, at times—but also sheltered and safeguarded by a rugged landscape and a clannish culture. This isolation has yielded some distinct, if not gloriously peculiar, folkways celebrated, once again, in Singin’, Praisin’, and Raisin’: The Foxfire 45th Anniversary Book, an expansive oral history collected by high-school students in the Foxfire program, based in Mountain City, Georgia, and edited by Joyce Green and Casi Best.

Published in August by Anchor Books, it features the usual entertaining cast of moonshiners, conjure-wimmin, and “boogers and haints”—all of them flinty, hard-working types—with a special emphasis on music. For the first time in the series, this edition offers a companion compact disc of twangy pickers from its “Echoes” chapter, including mainstays like The Primitive Quartet, as well as others such as LV and Mary Mathis, a seasoned, husband-and-wife duet never recorded until now. (The initials stand for “Lyin’ Varmint,” Mary jokes.)

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-